A strong economy is built on the backs of its workers, but not all labor creates equal value. In Pakistan, much of the workforce is trapped in roles that offer no upward mobility, generate little economic output, and do not contribute meaningfully to long-term national growth. Jobs such as domestic service, often rooted in outdated class structures, do little to empower individuals or enhance productivity. Labor should not be about servitude. It should be about participation in a system where work builds both personal dignity and public wealth.

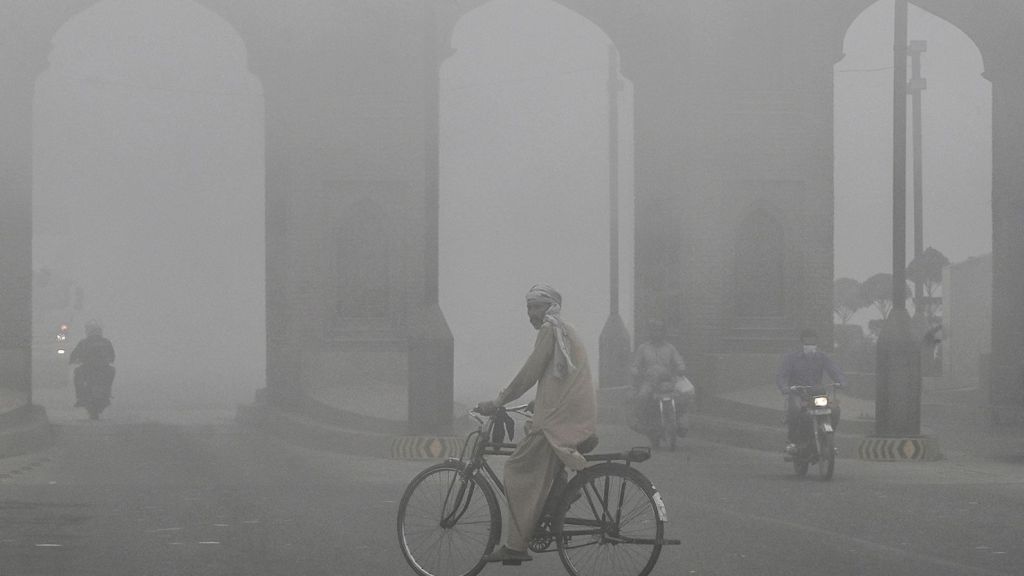

As of 2020–21, over 37 percent of Pakistan’s labor force is employed in agriculture, 25 percent in industry, and about 37 percent in services. While these figures appear balanced on paper, in practice, large segments of this labor are informal, low-skilled, and underpaid. Informal employment dominates across all sectors, leaving workers without job security, social protections, or prospects for skill advancement. This is particularly true in domestic work, retail, and low-end services where millions, especially women, remain stuck in stagnant, unprotected employment.

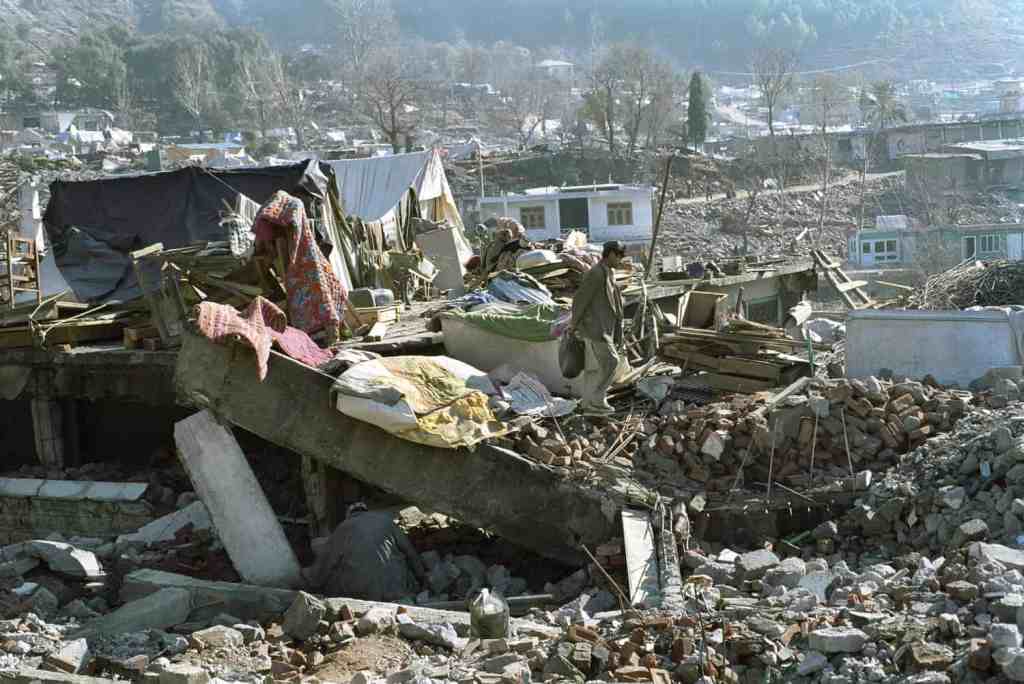

Such a system does not just harm individuals. It constrains national economic potential. Low-productivity labor generates minimal tax revenue, stifles innovation, and reproduces cycles of poverty. Worse, the rigid class hierarchies in Pakistan mean that these roles are often assigned not based on skill or merit, but on inherited social status. Children born into poor families grow up expecting to work as drivers, servants, or informal laborers, with few pathways into sectors that actually create value such as manufacturing, technology, logistics, healthcare, or education.

For Pakistan to transition into a modern, high-output economy, the structure of its labor market must change. This begins with large-scale investment in industries that generate measurable economic value and offer long-term careers, such as textiles, energy, IT services, construction, agriculture technology, and clean manufacturing. Vocational and technical training must be realigned to meet the actual needs of these sectors. Schools and colleges should form pipelines into apprenticeships and jobs that pay fair wages and offer professional growth.

Additionally, informal sectors must be formalized. Small businesses, tradespeople, and home-based workers should be brought into the economic mainstream through registration, credit access, and legal protections. The private sector should be incentivized to transition informal workers into formal contracts with guaranteed benefits.

Gender equity is also essential. Women’s labor force participation in Pakistan remains far below regional and global averages. The solution is not to push women into traditional care or household roles but to open space in high-growth sectors through safe transport, inclusive hiring practices, on-site childcare, and education focused on digital and technical skills.

Pakistan must also address the structural inequality that has long shaped its labor landscape. This includes dismantling the entrenched class system that normalizes menial, stagnant roles for the working poor. A just labor policy must enable every citizen, regardless of background, to pursue a life of dignity, mobility, and contribution to the nation’s future.

In the 21st century, labor should mean creation. It should build the individual while strengthening the country. Every job must be judged not just by whether it fills time or puts food on the table, but by whether it produces something of real value to the worker, the economy, and society.

The transformation of East Asian economies was not the result of chance. It was the product of long-term planning, widespread education reform, strategic industrialization, and the belief that labor must be both productive and dignified. Economies such as China, Taiwan, and South Korea rose from poverty into global manufacturing and technology hubs by channeling labor into industries that produced real economic value. They created millions of jobs that not only paid wages, but built skills, created exports, and supported families for generations.

In Taiwan and South Korea, the first step was universal education, with a focus on science, engineering, and technical skills. High school students were streamed into academic or vocational paths, both of which were respected and supported. The state heavily invested in polytechnic institutes and public universities that were aligned with industrial policy. These institutions produced engineers, technicians, and machinists at scale, ready to join manufacturing firms, electronics assembly lines, or infrastructure projects. Education was not abstract. It was tied directly to jobs.

China followed a similar path, combining mass training with massive industrial development. The government established thousands of factories in special economic zones, often built near transportation hubs, ports, and power stations. Workers were trained to assemble electronics, manufacture steel, build machinery, and operate precision tools. The focus was not on short-term profit but on building capacity and capabilities that would serve the country for decades. At the heart of this effort was the idea that every worker could be part of national development if given the opportunity.

Pakistan has yet to take this path in a coordinated way. The country has the population size, geographic advantage, and entrepreneurial spirit to build a high-output economy, but the state has not yet aligned its education, labor, and industrial policies toward that goal. A serious transformation begins with the understanding that low-skill labor is not enough. Labor must produce value for the individual and for the economy. That means moving beyond domestic service, informal retail, or low-wage construction jobs and into industries that have structure, scale, and strategy.

First, Pakistan must reform its education and training systems. Technical education should be available and accessible in every province. Polytechnics and vocational colleges should receive national-level funding and be directly connected to industrial zones. Training must be practical, modern, and industry-driven. Schools should be equipped with tools, machinery, and labs that allow students to learn with their hands and graduate ready for employment in manufacturing, logistics, construction technology, electrical systems, and other growth sectors.

Second, the state must invest in its industrial base. Infrastructure is the foundation of labor opportunity. Roads, electricity, water, and broadband must be extended to new industrial zones outside major cities. These zones should be focused on sectors where Pakistan has comparative potential such as textiles and garments, surgical instruments, processed food, construction materials, renewable energy components, and assembly of electronic goods. Domestic firms should be supported with long-term credit and export assistance while foreign firms should be attracted with the condition that they hire and train local workers.

Third, the government must ensure labor rights and stability. Workers who enter these new industries should be protected by fair contracts, workplace safety laws, and opportunities for progression. A manufacturing job should not be a dead-end but a stepping stone to technical supervision, quality control, or even entrepreneurship. In Taiwan and South Korea, many factory workers eventually opened their own small firms, which became the foundation of a robust small and medium enterprise sector.

Finally, this transformation requires long-term planning and consistency. East Asia succeeded because governments committed to multi-decade strategies and avoided political disruptions in key policies. Pakistan must do the same. Ministries, provinces, public education boards, and private sector associations need to operate from a shared vision. Creating labor with real value is not a five-year plan. It is a twenty-year commitment to reshaping the foundations of the economy.

The goal is clear. Every Pakistani worker should be able to enter a job that provides a living wage, teaches a skill, and contributes to national production. When labor is structured, respected, and connected to industry, it becomes the engine of development not just for individual families but for the country as a whole.