Pakistan, with its vast population, rapidly urbanizing cities, and growing industrial hubs, is primed for a national transformation in how people and goods move. A modern, high-speed rail (HSR) system—capable of connecting Lahore, Karachi, Islamabad, Faisalabad, Multan, Peshawar, and other key cities—would not only be a technological leap forward but also a unifying national infrastructure project on par with the creation of the motorway network or the Indus Basin irrigation system. It is a step Pakistan can and must take.

With over 240 million people, Pakistan is the fifth most populous country in the world. Its major metropolitan centers are separated not by vast wilderness but by dense belts of agricultural and peri-urban development. A high-speed rail network would thread through this economic heartland, linking cities that together produce the bulk of Pakistan’s GDP. According to World Bank estimates, urban centers contribute nearly 55 percent of national economic output. Yet current transportation options are inefficient, congested, and unable to keep pace with the growing needs of a mobile, interconnected population.

The case for HSR is grounded in more than convenience. It is a tool for national integration, economic modernization, and energy-efficient mobility. High-speed rail reduces dependence on fossil-fuel heavy road transport and domestic air travel. It brings periphery regions closer to industrial cores. It unlocks mobility for students, workers, and traders who otherwise spend hours on crowded highways or cannot afford air travel.

With the right planning and commitment, Pakistan can follow suit, using HSR not just as a symbol of modernity, but as a strategic asset that strengthens the economic spine of the country.

From Colonial Relic to an Opportunity for a New National Backbone

Pakistan’s railway network remains, in large part, a legacy of British colonial rule. Much of its layout, gauge width, and even station placement were designed over a century ago, not to connect communities or serve the people, but to transport raw materials and extract resources efficiently for imperial interests. These lines, once engineered to serve the British Raj’s logistical needs, have seen little transformative change since independence in 1947.

Current Pakistani locomotives are decades behind.

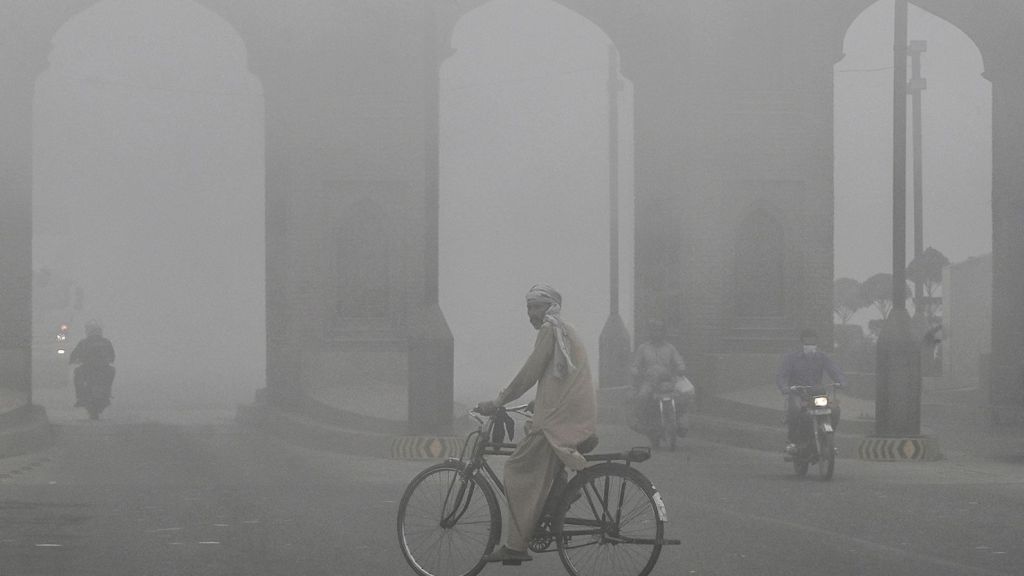

Despite being one of the largest railway networks in the region, Pakistan Railways has struggled to evolve into a modern, reliable system. Infrastructure is outdated, signaling systems are largely manual, and electrification is minimal—covering just a fraction of the network. The average speeds of passenger trains remain stuck around 60 to 80 kilometers per hour, with many sections of track still reliant on aging bridges and poorly maintained lines.

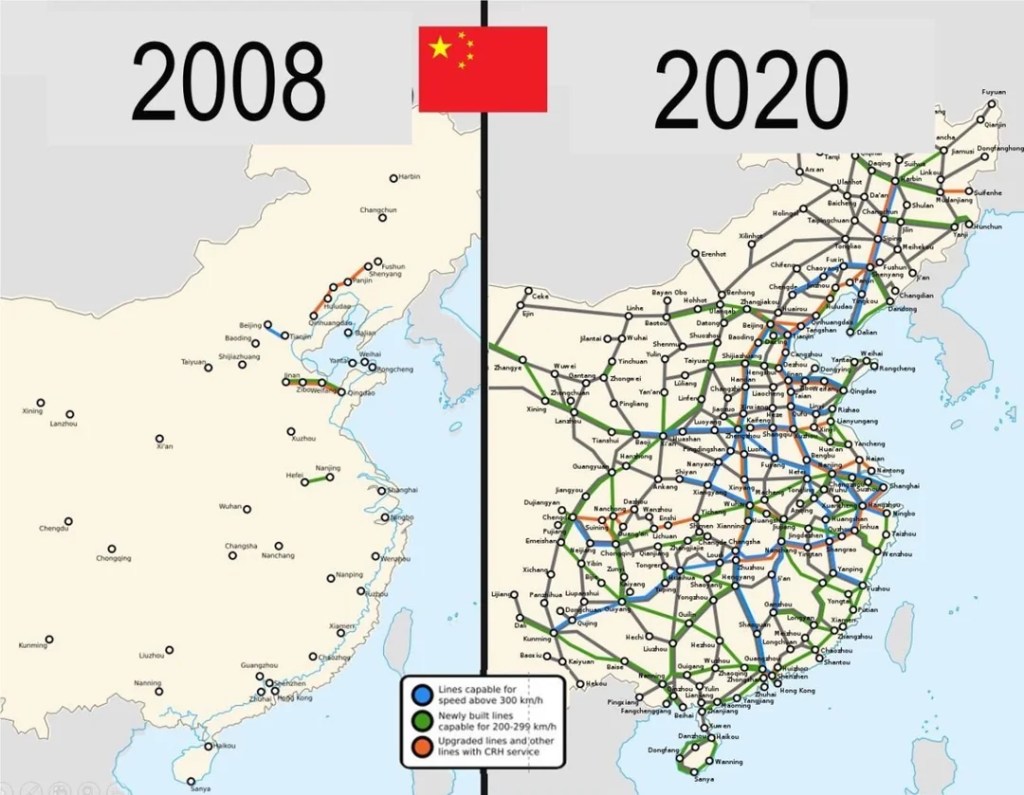

In contrast, regional peers have taken decisive steps toward rail modernization. India has introduced its first indigenously developed semi-high-speed trains, the Vande Bharat Express, which operate at 160 km/h and are planned to scale across dozens of routes. China has gone even further, creating the world’s largest high-speed rail network spanning over 42,000 kilometers. These developments did not occur overnight, but through consistent long-term planning, public investment, and an acknowledgment that rail infrastructure is central to economic mobility and national cohesion.

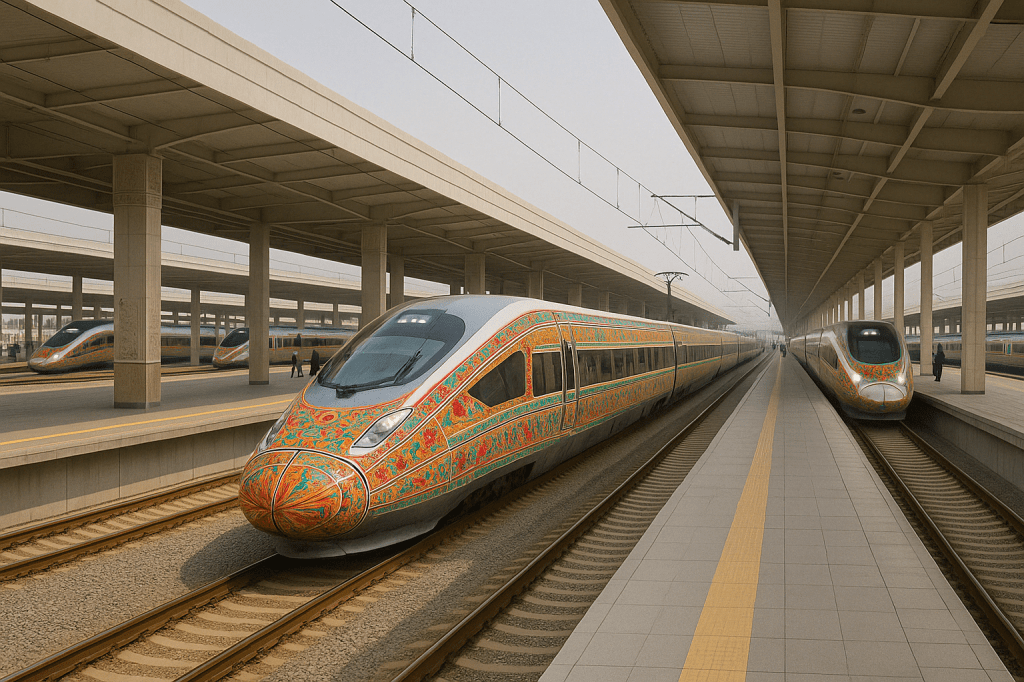

The Chinese had a clear vision and delivered on their HSR network.

The stagnation in Pakistan is not due to an absence of need or potential, it is due to a lack of prioritization. In a country where millions travel between cities each week, where urban congestion and fuel costs are rising, and where the working population is rapidly expanding, the absence of a modern rail system is not just an inconvenience, it is a missed opportunity.

The comparison is clear. India and China turned inherited colonial or outdated infrastructure into systems that now serve the heart of their industrial and economic agendas. Pakistan has the same starting materials: dense cities, strategic geography, a young workforce, and growing freight and passenger demand. What it lacks is the political will to transform its railway system from an artifact of the past into an engine of future growth.

Iron Brothers, Iron Horses: Building the Future of Rail Together

China’s HSR is an applicable proof of concept for Pakistan.

Pakistan and China have often referred to themselves as “Iron Brothers”—a term that symbolizes a deep, strategic, and time-tested partnership. As Pakistan stands on the cusp of transforming its outdated railway infrastructure, there is no better partner to help guide this journey than China, the global leader in high-speed rail development. The very metaphor of the “iron horse,” once used to describe locomotives during the Industrial Revolution, now takes on new meaning. It represents both the physical trains that could connect Pakistan’s cities and the strength of cooperation that can make it possible.

China’s high-speed rail (HSR) network is the most advanced and expansive in the world, spanning over 42,000 kilometers. It has been built in less than two decades through a combination of state-led investment, technology development, and workforce training. Pakistan, with its close diplomatic and economic ties to China—especially under the framework of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)—is uniquely positioned to benefit from this experience.

Already, cooperation in rail is underway through the Main Line 1 (ML-1) project, which aims to upgrade Pakistan’s most critical railway corridor from Karachi to Peshawar. This $6.8 billion initiative includes plans to double-track the line and raise train speeds to 160 km/h. While this is a major step forward, Pakistan can and must go further. High-speed passenger rail capable of exceeding 250 km/h, intercity express routes, and dedicated freight corridors are within reach, if designed and built with vision.

Pakistan would need to vertically integrate it’s production in all aspects.

What makes China’s model appealing is not just its scale, but its strategy. It invests in domestic manufacturing of rail components, develops human capital through vocational and engineering programs, and prioritizes long-term returns over short-term cost-cutting. Pakistan can adopt a similar approach. By using Chinese technical guidance to train local engineers, standardize rail design, and establish domestic production lines for rolling stock and signaling equipment, Pakistan can internalize both the knowledge and the means of railway modernization.

Such collaboration doesn’t have to result in dependency. Instead, it can build domestic capability, enhance technological self-reliance, and strengthen the national economy. It can turn Pakistan into a country that not only runs modern trains, but builds them, maintains them, and exports that knowledge regionally.

In this next phase of development, the symbolism of the Iron Brothers should move from the rhetorical to the material. Together, Pakistan and China can lay down tracks—not just across land, but toward a future of shared industrial growth, regional integration, and technological strength. The iron horse can once again roar, not as a relic of the past, but as the engine of a new era.

Envisioning a Modern Pakistan: What a Nationwide High-Speed Rail Network Could Look Like

Major metro areas would be connected via high-speed rail.

A functional, efficient high-speed rail (HSR) system in Pakistan should be built around the country’s existing urban and economic geography. With over 60 percent of the population living in the Indus River corridor and key cities spaced 200–600 kilometers apart, the country is naturally suited for rail-based intercity travel. A nationwide HSR network would not only serve this dense belt but integrate outlying regions, balancing growth and improving mobility.

The core spine of the system should run from Karachi to Peshawar, connecting major cities such as Hyderabad, Sukkur, Multan, Lahore, Rawalpindi, and Islamabad. This north-south corridor spans approximately 1,500 kilometers and overlaps with Pakistan’s most heavily traveled and economically vital routes. With trains operating at 250–300 km/h, travel times would be reduced by over two-thirds. Karachi to Lahore would become a six-hour journey instead of nearly a full day. Islamabad to Multan could be completed in just over two hours.

Secondary spurs would then branch out to key cities such as Faisalabad, Sialkot, Gujranwala, Bahawalpur, Quetta, and Abbottabad, creating a true national grid. These cities are not just population centers; they are hubs of commerce, textile production, logistics, agriculture, and tourism. Connecting them efficiently through rail would unlock substantial passenger demand while also supporting industrial freight corridors.

With this kind of network, Pakistan could realistically move over 200 million rail passengers annually within 15 years—nearly quadrupling current ridership. Cities like Lahore and Karachi, which each see over 10 million daily urban trips, would become better connected to their regional hinterlands. Multan to Lahore, currently a four- to five-hour drive, could become a 90-minute commute—encouraging regional integration, labor mobility, and day travel.

A generated image of a Pakistani-style bullet train.

A phased rollout could begin with the Lahore–Rawalpindi–Peshawar segment, due to its manageable distance, high population density, and relatively developed rail corridor. From there, the Lahore–Multan–Sukkur–Karachi section could follow, knitting together the country’s industrial and commercial heartland. Future extensions westward to Quetta, and potentially even cross-border linkages into China or Central Asia, could position Pakistan as a regional rail hub.

To support this vision, major urban stations would need to be reimagined as modern multi-modal hubs—integrating buses, metros, parking, and last-mile connectivity. High-speed rail does not exist in isolation; its success depends on strong linkages to local transportation and city planning.

A well-designed HSR network is not just about faster trains—it’s about a faster Pakistan. A country where business meetings, family visits, medical appointments, and cargo deliveries are no longer slowed by aging roads and bottlenecked infrastructure. It would be a nation on the move—linked by steel, powered by innovation, and connected by purpose.

Reviving Industry, Empowering Labor: A Strategic Leap for Pakistan’s Economic Base

A high-speed rail project has the potential to become more than a transportation initiative. It can serve as a platform for the revival of Pakistan’s industrial core, while creating meaningful work for millions of skilled and unskilled laborers across the country. The success of this undertaking lies not just in kilometers of track laid, but in how deeply it engages the national economy and workforce at every level.

Pakistan’s industrial landscape has been underutilized for decades. Despite having established sectors in steel, cement, heavy equipment, and electrical manufacturing, much of the country’s production capacity remains fragmented or import-dependent. A large-scale rail project would provide sustained, coordinated demand for raw materials, semi-finished products, and finished components. Domestic steelmakers would receive long-term orders for rails, fasteners, and structural supports. Cement and aggregate producers would benefit from consistent demand for foundational work, tunnels, and viaducts. Local factories could begin assembling or even manufacturing rolling stock, track panels, and electrical systems, building technical capabilities that would outlast the project itself.

Indonesia’s HSR project created opportunity for skilled domestic labor.

The benefits would not be limited to industrialists or urban centers. Infrastructure of this scale reaches into every region it crosses. Bringing with it jobs, contracts, and training opportunities. Roadside welders, machine operators, masons, carpenters, and electricians—millions of Pakistanis with hands-on experience but little formal training—would be drawn into a structured national effort. With proper technical supervision and targeted vocational programs, these workers would not only contribute to the project, but emerge from it with transferable skills. They would become part of a modern, professional class of labor tied to nation-building, not just subsistence.

This is the kind of development that lifts economies from the bottom up. It treats labor not as a cost to be minimized, but as a capacity to be cultivated. The long-term gains are profound. A welder trained on railway infrastructure can later work on power grids, factories, or export-oriented industrial parks. A foreman managing a rail segment in Baluchistan can later supervise housing, energy, or road development. A modern workforce begins with modern projects—and high-speed rail offers just that.

In parallel, regional economies surrounding rail corridors would experience secondary growth. Small manufacturers, logistics hubs, service providers, and agricultural distributors would find new markets accessible through fast and affordable transport. Economic activity would begin to cluster along the rail spine, generating organic urban development and reducing pressure on megacities.

The broader vision is clear. High-speed rail is not just a physical connection between cities. It is an economic instrument to connect capital with labor, demand with supply, and technical ambition with local capacity. It is a chance to reorganize Pakistan’s economy around productive activity, national skill-building, and long-term industrial strength.

A nation that builds for itself, using its own hands, talent, and resources, does not just improve its infrastructure. It builds confidence, identity, and economic dignity. That is what high-speed rail can offer to Pakistan.

A Rail-Driven Future Within Reach

California’s troubled HSR project emphasizes the importance of willpower.

High-speed rail is not beyond Pakistan’s capabilities. It is well within them. What is required is not permission from international lenders, nor validation from global institutions, but a clear national will to build. Pakistan has the raw materials, the manpower, the geography, and most importantly, the need. The only missing ingredient is commitment.

A country does not need to be rich to begin building its future. It needs direction. It needs leadership that believes in its own people and trusts in their ability to create. Pakistan does not need to take on unsustainable loans, play by rules written elsewhere, or wait for external actors to approve its ambitions. What it needs is to mobilize what it already has, its workers, its engineers, its factories, and its collective energy. The resources are here. The people are ready. The blueprint is clear.

High-speed rail is more than just a project. It is a symbol of what a nation can do when it chooses to rely on itself. It is a chance to channel the labor of the many into something permanent, useful, and unifying. It creates real jobs, revives real industries, and offers real mobility. It connects not just cities, but classes and regions and generations.

This is the kind of work that builds a country in the truest sense. And it does not have to wait.

In a follow-up article on this topic, I will present a phased implementation strategy, showing how Pakistan can begin, where the first lines should run, and how this vision can grow responsibly and effectively. But the most important thing to understand is this: the path forward does not lie elsewhere. It lies here. In the hands of those who are ready to build.