In recent years, pollution in Pakistan has reached levels so extreme that the air itself has become a public health hazard. Cities like Lahore and Karachi are routinely blanketed in toxic smog, with Air Quality Index (AQI) readings regularly exceeding 300 and in some cases soaring past 1,900. In 2024, Multan recorded an AQI of 2,553 with PM2.5 concentrations hitting 947 µg/m³, nearly 190 times higher than the World Health Organization’s recommended limit. These are not one-off spikes. These are becoming seasonal norms.

The health consequences are severe and far-reaching. According to the University of Chicago’s Air Quality Life Index, the average Pakistani loses 3.9 years of life due to air pollution. In the most affected regions like Lahore and Peshawar, that figure climbs to nearly seven years. Respiratory diseases, cardiovascular complications, strokes, and lung cancer are all on the rise, conditions directly linked to prolonged exposure to fine particulate matter. For children, the situation is even more dire. Over 11 million children under the age of five in Punjab alone are breathing air so toxic it contributes to roughly 12 percent of deaths in that age group. The damage is long-term, irreversible, and utterly preventable.

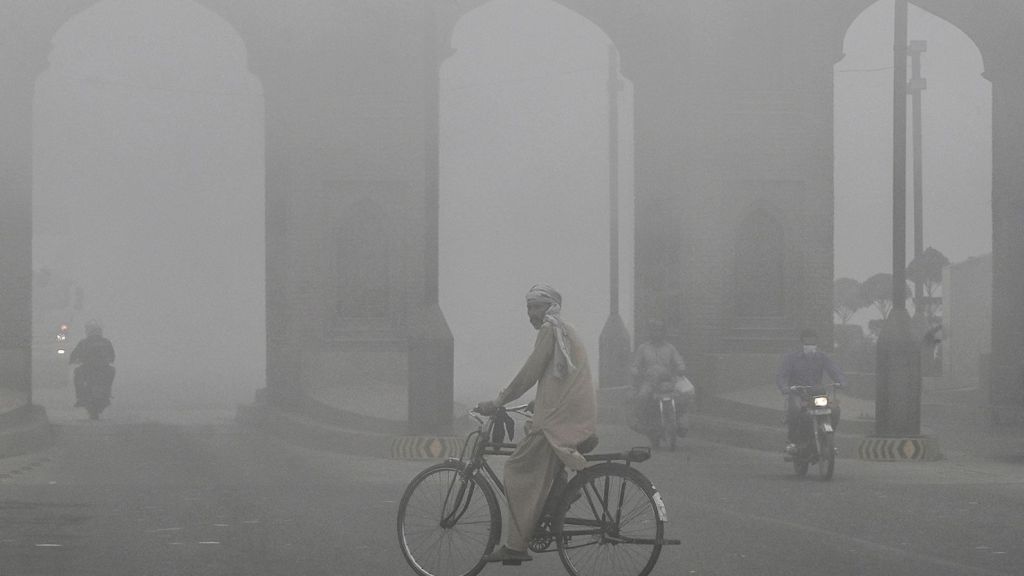

Lahore’s pollution disguises iconic landmarks in an orange tint.

This is not just a health crisis. It is an economic one too. Pakistan loses nearly $48 billion annually to pollution-related costs, a figure that represents close to 6 percent of its GDP. Lost productivity, mounting healthcare expenses, reduced agricultural output, and disruption to education and transportation all pile onto a national burden that continues to grow unchecked.

And yet, amid all of this, a dangerous sense of normalcy is setting in. Masked schoolchildren navigating yellow skies, coughing pedestrians, and smog warnings on the news are becoming routine. But this cannot be the standard Pakistan accepts. Pollution is robbing the country of its future, not only in the form of years lost but in the loss of potential, of health, and of dignity. Recognizing the scope of this crisis is the first step. What comes next must be a reckoning at every level of society to demand air that does not kill.

The Anatomy of Pakistan’s Pollution Crisis

To understand the scale of Pakistan’s air pollution crisis, one must examine the complex web of its sources, the geographic patterns that emerge across provinces, and the underlying structural issues that have allowed this environmental catastrophe to unfold unchecked. Air pollution in Pakistan is not the result of a single cause but rather a convergence of deeply rooted industrial practices, outdated infrastructure, policy gaps, and seasonal agricultural behaviors.

One of the largest contributors to Pakistan’s deteriorating air quality is vehicular emissions. As of 2023, there were over 32 million registered vehicles in the country, with two-wheelers accounting for the majority. Most of these operate without catalytic converters and use low-grade fuels, resulting in disproportionately high emissions of nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, and particulate matter. Public transportation remains underdeveloped, and rapid urbanization has only increased reliance on personal vehicles and informal transport networks, both of which are largely unregulated and emissions-heavy.

Most of Pakistan’s 32 million registered vehicles operate without any environmental mitigation taken into account.

Industrial output is another major driver of air pollution, particularly in urban and peri-urban zones. Brick kilns, a widespread industry with over 20,000 active sites across the country, burn low-quality coal, rubber tires, and other toxic waste to fire bricks. Each kiln can emit hundreds of kilograms of fine particulate matter per day during peak operation. Although zigzag kiln technology has been introduced as a cleaner alternative, adoption remains limited due to cost barriers and lack of regulatory enforcement.

Agricultural burning, especially in Punjab, adds another seasonal layer to this crisis. In the post-harvest months of October and November, large-scale crop residue burning releases clouds of black carbon and fine particulate matter into the air. This practice not only affects rural populations but also drifts into nearby cities, exacerbating urban smog. In 2024, satellite data recorded more than 33,000 fire events linked to crop burning in Punjab and northern India, contributing significantly to the cross-border smog that engulfed Lahore and its surroundings.

Crop burning is an unsustainable practice.

Waste incineration and open-air garbage burning further intensify the problem, particularly in urban slums and rural outskirts where formal waste collection is either ineffective or nonexistent. It is estimated that over 40 percent of municipal solid waste is burned openly in Pakistan, releasing a toxic mix of dioxins, furans, and particulate pollutants into the atmosphere.

The geography of the crisis reveals stark contrasts and troubling trends. Lahore, Faisalabad, Gujranwala, and Peshawar consistently rank among the world’s most polluted cities during the winter months. Lower temperatures, stagnant air, and thermal inversion trap pollutants close to the ground, creating dense smog that lingers for weeks. This seasonal smog, often referred to as a “fifth season” in Punjab, has become an annual phenomenon that disrupts life and drives up hospital visits due to respiratory illnesses.

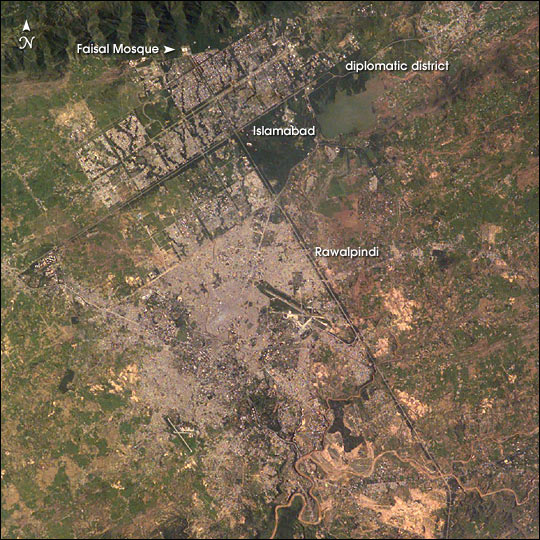

Unregulated urban expansion is a central factor in exacerbating this crisis. Cities like Lahore and Karachi have expanded rapidly without adequate urban planning, zoning laws, or environmental considerations. Construction booms have consumed green belts and agricultural lands, replacing them with concrete sprawl and traffic congestion. Deforestation, absence of green infrastructure, and a lack of sustainable transit systems have turned these cities into pollution traps.

The difference between planned urban development is stark at the Islamabad / Rawalpindi divide.

Outdated infrastructure further compounds the issue. Most roads lack proper paving or maintenance, which increases dust pollution, while the absence of efficient mass transit systems means more vehicles are added to the road every year. Regulatory oversight remains weak, and environmental protection agencies are underfunded and politically constrained, unable to enforce emissions standards or regulate polluting industries effectively.

The anatomy of Pakistan’s pollution crisis is both structural and behavioral. It is embedded in the way cities are designed, how industries operate, and how natural cycles are disrupted to accommodate immediate economic interests. Without a coordinated, multi-sectoral response that addresses both the root causes and the enabling conditions of pollution, the crisis will continue to worsen. The consequences are not abstract. They are measured in lives lost, health systems strained, and economic potential eroded across generations.

Health Fallout — A Public Health Emergency

Air pollution in Pakistan is no longer just an environmental concern; it is a full-scale public health emergency with measurable and compounding impacts on nearly every segment of society. The toxic air that blankets major cities and industrial regions is responsible for a range of acute and chronic illnesses, many of which have reached epidemic proportions in affected areas. The burden is most visible in respiratory and cardiovascular health outcomes, but the ripple effects extend across age groups, healthcare systems, and long-term development indicators.

The short-term effects of exposure to high concentrations of fine particulate matter, especially PM2.5, include coughing, wheezing, asthma attacks, bronchitis, and increased susceptibility to infections. In Lahore, where PM2.5 concentrations regularly exceed 200 µg/m³ during peak smog months, emergency rooms report sharp upticks in patients with breathing difficulties. Long-term exposure leads to far more serious conditions. Prolonged inhalation of polluted air is directly linked to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), ischemic heart disease, strokes, and lung cancer. A 2023 study from Aga Khan University found that people living in high-pollution zones in Punjab were up to 40 percent more likely to suffer from heart disease compared to those in cleaner areas.

Children are particularly vulnerable. Their developing lungs and immune systems make them more susceptible to air pollutants. According to UNICEF, over 11 million children under the age of five in Punjab alone are exposed to hazardous levels of air pollution. This contributes to impaired lung function, cognitive development issues, and a higher risk of pneumonia, which remains one of the leading causes of death among children under five in Pakistan. Pregnant women are also at heightened risk. Studies from Pakistan’s National Institute of Health have linked air pollution to increased instances of low birth weight, premature birth, and even stillbirth. The elderly, particularly those with pre-existing health conditions, face increased risks of stroke, heart attacks, and respiratory failure during smog season.

Sick children being treated for pollution related illness in Lahore.

The strain on Pakistan’s already overburdened public health infrastructure is immense. Tertiary care hospitals in major cities like Lahore, Karachi, and Faisalabad report seasonal spikes in admissions during the winter months, when smog and pollution levels peak. According to the Punjab Health Department, hospitalizations due to respiratory complications increased by nearly 25 percent during the 2022–2023 smog season. Clinics in peri-urban areas often lack the necessary respiratory support equipment such as nebulizers, oxygen tanks, or ventilators, leaving the most vulnerable patients untreated or referred to overcrowded urban centers.

Moreover, the economic burden associated with pollution-related illness is staggering. A 2022 report by the World Bank estimated that air pollution contributes to the loss of nearly 229,000 lives annually in Pakistan and costs the economy $47.8 billion per year. This loss is not only measured in healthcare expenditures and mortality rates, but also in lost workdays, reduced academic performance among children, and a workforce increasingly debilitated by preventable illnesses.

Air pollution in Pakistan must be seen as a public health crisis requiring the same level of national urgency as outbreaks of infectious disease. Its effects are slow-moving but deeply corrosive, damaging the country’s human capital and reducing quality of life for millions. Addressing this crisis is not just about clean air; it is about preventing a public health collapse that Pakistan’s infrastructure is ill-equipped to manage without aggressive, sustained intervention.

Economic Impact — The Hidden Drain

The economic consequences of pollution in Pakistan are vast, often overlooked in public discourse but deeply corrosive to national development. While the visible signs of toxic air—smog-covered cities, closed schools, and overwhelmed hospitals—draw intermittent attention, the long-term damage to the economy is structural and escalating. It is not simply a cost Pakistan bears for industrial activity or urban growth; it is a hidden tax on every citizen, business, and institution.

Air pollution currently costs Pakistan an estimated $47.8 billion annually, according to the World Bank. This figure represents nearly 6 percent of the country’s GDP and includes both direct costs such as healthcare and indirect costs like lost productivity and environmental degradation. Healthcare alone accounts for a significant share. Treating pollution-induced illnesses—respiratory infections, strokes, heart disease, and asthma—places heavy strain on public health systems and household finances alike. During peak pollution periods, hospitals in cities like Lahore report surges in patients requiring emergency care, oxygen support, and extended hospitalization. For many low- and middle-income families, recurring medical expenses from preventable illnesses erode savings and reduce disposable income.

Labor productivity takes a major hit as well. High levels of particulate pollution reduce worker efficiency, increase absenteeism, and shorten working lifespans, particularly among those in outdoor sectors such as agriculture, construction, and transportation. With over 60 percent of Pakistan’s workforce engaged in informal or manual labor, this loss is widespread and poorly documented. Studies have shown that exposure to PM2.5 can lower cognitive function and physical stamina, both critical for economic output. As days lost to illness increase, the country’s economic engine slows.

Labor is unable to be productive in such high pollution.

Perhaps the most underappreciated consequence of air pollution is its impact on agriculture. In a country where nearly 40 percent of the population depends on farming for income and where food security is a persistent challenge, Pakistan cannot afford to let pollution undermine crop yields. Fine particulate matter and ground-level ozone reduce photosynthesis efficiency, damage leaf structures, and contaminate soil quality. Crops such as wheat, rice, sugarcane, and cotton—all staples of Pakistan’s agricultural economy—have been shown to experience reduced output under polluted conditions. In Punjab, the nation’s agricultural heartland, satellite imagery and field data reveal a consistent decline in crop productivity during peak smog months. For a country that should be striving for self-sufficiency in food production to meet the demands of its rapidly growing population, these losses are particularly dangerous. They increase dependency on expensive food imports and expose the country to price shocks in the global commodity market.

Education and tourism sectors also suffer. Schools in major cities like Lahore and Faisalabad are often forced to close or shorten operating hours during smog seasons, disrupting academic progress for millions of students. Prolonged closures and reduced attendance during crucial months of learning have long-term implications for national human capital. The tourism sector, already underperforming, struggles further as polluted skylines and international air quality warnings deter visitors. This not only impacts revenue but also harms local economies in regions that rely on seasonal tourism.

Other forms of pollution also impact Pakistan’s tourism.

Foreign investment is increasingly influenced by environmental factors. Multinational corporations and institutional investors evaluate environmental risks when choosing business locations. Poor air quality affects employee health, increases operating costs, and damages a company’s environmental and social responsibility profile. Without demonstrable progress on pollution control, Pakistan risks exclusion from emerging green investment opportunities and environmentally linked trade partnerships.

The most critical insight is that the cost of inaction far outweighs the investment needed to mitigate pollution. Implementing clean public transport systems, regulating vehicle emissions, converting brick kilns to cleaner technologies, and transitioning to renewable energy sources all require upfront investment. Yet these investments have high economic returns in the form of reduced healthcare costs, increased productivity, and strengthened resilience across sectors. Every dollar spent on clean air yields not just savings, but growth and opportunity.

Pollution is eroding the foundations of Pakistan’s economy. It weakens the health of its people, slows down its industries, damages its farms, and undermines its competitiveness. For a country with a young workforce, abundant agricultural potential, and growing urban centers, clean air must be treated not as an environmental ideal but as an economic necessity. Without it, the promise of development will remain out of reach.

Environmental Degradation and Climate Synergy

Air pollution in Pakistan is not an isolated phenomenon. It exists within a larger web of environmental degradation that is accelerating the country’s vulnerability to climate change and natural resource scarcity. The interaction between pollution, water stress, land degradation, and climate variability forms a dangerous feedback loop that threatens the ecological and economic future of the country.

As an already water scarce country, pollution further threatens to limit what fresh water is available.

One of the most direct and damaging intersections is between pollution and water scarcity. Pakistan is already among the most water-stressed countries in the world, with per capita water availability dropping below 1,000 cubic meters per year, the threshold for water scarcity as defined by the World Bank. Industrial emissions and the open burning of waste release heavy metals and toxic compounds into the atmosphere. These pollutants eventually settle into water bodies through precipitation, contaminating rivers, lakes, and groundwater reserves. In urban centers like Karachi and Lahore, runoff from polluted air and waste disposal has severely impacted the quality of drinking water. The Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources has reported that nearly 70 percent of water samples collected in major cities are unsafe for human consumption due to microbial and chemical contamination, much of it linked to airborne pollutants.

Climate change amplifies these pressures. Rising temperatures caused by greenhouse gas emissions from transport, industry, and energy production are intensifying heatwaves, altering precipitation patterns, and increasing the frequency of extreme weather events. Pakistan is particularly vulnerable, ranking eighth on the Global Climate Risk Index. Air pollutants such as black carbon not only harm human health but also contribute to regional warming by absorbing sunlight and accelerating glacial melt in the Himalayas. The melting of glaciers, which provide up to 60 percent of Pakistan’s water through river systems, poses a long-term threat to water security and agricultural sustainability.

Urbanization without environmental regulation has led to the formation of heat islands in cities like Lahore, Islamabad, and Karachi. As green spaces are replaced by concrete and asphalt, and as vehicle and industrial emissions rise, urban areas trap heat during the day and release it at night, creating temperature differentials as high as 7 degrees Celsius compared to surrounding rural areas. These heat islands increase electricity demand, worsen air quality, and make cities unlivable during the summer months. In 2022, Karachi experienced a deadly heatwave with temperatures exceeding 44 degrees Celsius, resulting in hundreds of heat-related deaths and overwhelming hospital systems.

The result of illegal logging in northern Pakistan.

Deforestation adds another layer to this crisis. Pakistan’s forest cover is estimated to be less than 5 percent of its total land area, far below the recommended global average of 25 percent. Illegal logging, urban expansion, and agricultural encroachment have accelerated the loss of tree cover. Forests are crucial for filtering air, regulating water cycles, and preserving soil quality. Their removal not only worsens air quality but also increases the risk of landslides, floods, and desertification. The Margalla Hills, once a thriving green zone near Islamabad, have lost large tracts of forest to unchecked development and mining activity.

The consequences for biodiversity are alarming. Pakistan is home to more than 780 species of birds, 177 species of mammals, and 198 species of reptiles. Many of these species are increasingly threatened by habitat loss, changing temperature zones, and the bioaccumulation of airborne toxins in their food and water sources. The Indus River dolphin, a freshwater mammal already classified as endangered, faces extinction due to a combination of water pollution and habitat fragmentation. Agricultural ecosystems are also at risk. Pollutants that settle on soil and water disrupt plant growth, reduce crop resilience, and decrease pollinator activity. This threatens not only food security but also the long-term ecological balance of rural economies.

The already threatened Indus River Dolphin, endemic to Pakistan, is further threatened by pollution.

Pollution in Pakistan is not only a public health issue or an economic burden. It is a destabilizing force in the country’s entire environmental system. Its interaction with water scarcity, climate volatility, and ecological decline multiplies risk and reduces the country’s ability to adapt to future challenges. Unless pollution is addressed as part of a broader environmental and climate strategy, efforts to achieve sustainable development will remain fragmented and ultimately ineffective. The crisis requires an integrated approach that prioritizes environmental restoration, climate resilience, and pollution control as interlinked components of national survival.

Existing Policies and Institutional Gaps

Despite the scale and urgency of Pakistan’s pollution crisis, national and provincial responses have remained fragmented, reactive, and under-resourced. While some policy measures have been introduced over the past decade, they have largely fallen short of creating sustained improvements in air quality or environmental health. The failure lies not only in limited political will but also in the absence of robust institutions, real-time data infrastructure, and accountability mechanisms necessary for meaningful enforcement.

Pakistan’s environmental governance framework is centered around the Pakistan Environmental Protection Act of 1997, which established the Pakistan Environmental Protection Agency (Pak-EPA) and its provincial counterparts. These agencies are responsible for implementing environmental standards, monitoring emissions, and enforcing pollution controls. However, decades after their formation, they remain critically underfunded and lack the technical capacity to fulfill their mandates. For instance, the Lahore High Court has repeatedly intervened during smog seasons due to the failure of Punjab’s Environmental Protection Department to enforce brick kiln regulations, vehicle emissions standards, or industrial zoning laws. These judicial orders, while important, often result in short-term crackdowns rather than long-term reform.

Efforts such as the National Clean Air Policy and the Smog Commission recommendations have been drafted, yet implementation remains inconsistent. Policies are often broad in language, lacking timelines, clear metrics for success, or budgetary backing. In 2020, the Punjab government announced a plan to shift all brick kilns to zigzag technology by the end of the year. By 2023, a significant portion still operated on outdated, high-emission models due to poor enforcement and limited financial incentives for compliance. Similar patterns are observed in vehicular emissions testing, where inspections are rarely conducted, and public transport upgrades have stalled due to bureaucratic delays.

Pakistan’s brick kilns are problematic due to their debt traps, which is further exacerbated due to their inefficiencies and pollution.

One of the most critical institutional gaps is the lack of real-time environmental monitoring. While cities like Lahore and Karachi now feature independent air quality monitors installed by universities or NGOs, these efforts remain sparse and are not integrated into a national database. The absence of government-owned, transparent monitoring infrastructure means policymakers operate without reliable data to guide decisions. This also prevents citizens from knowing when the air they are breathing becomes hazardous, limiting public pressure for reform. A centralized air quality monitoring system, updated in real time and accessible to the public, would be transformative not only for policymaking but also for civic engagement and environmental education.

Accountability mechanisms are virtually nonexistent. Industries violating emission standards rarely face fines or shutdowns. Waste burning continues in urban neighborhoods without consequences. Construction sites ignore dust control regulations, and vehicle inspection centers function more as formalities than meaningful enforcement tools. Without accountability, existing policies are reduced to paperwork, disconnected from real-world impact. Strengthening environmental courts, empowering local governments with enforcement authority, and establishing independent audit bodies could significantly enhance compliance.

Despite these gaps, the path forward is not out of reach. Strengthening Pakistan’s environmental institutions would create ripple effects across multiple sectors. With empowered agencies, real-time data systems, and enforceable laws, the state could begin to reverse decades of degradation. Cleaner air would lead to improved public health, which in turn would reduce healthcare costs and boost labor productivity. Transparent monitoring systems would create pressure on both public and private actors to comply with environmental norms. Even modest investments in regulatory capacity and infrastructure could yield high returns.

Environmental governance is not a peripheral issue. It is central to economic growth, public well-being, and national resilience. Addressing institutional gaps is not just about building capacity—it is about reimagining the state’s role in protecting its citizens from one of the most pervasive threats to their future.

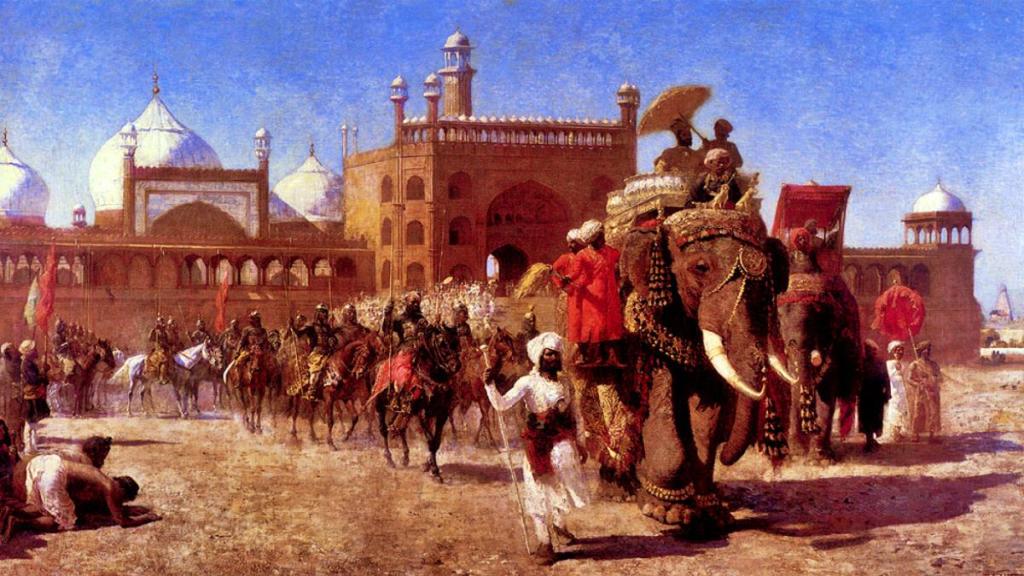

Comparative Global Models

The pollution crisis facing Pakistan is not unique. Countries across the Global South have grappled with similar challenges, from rapid industrialization and urban sprawl to weak regulatory institutions and high emissions from transport and agriculture. Yet several of these nations, most notably China, India, and Indonesia, have demonstrated that with targeted policies, institutional coordination, and sustained public pressure, it is possible to curb pollution without derailing economic growth. These cases offer valuable lessons for Pakistan and present a range of policy tools that can be adapted to its context.

Beijing’s policy changes resulted in the near elimination of constant smog.

China presents the most striking example of a successful national response to severe air pollution. Just a decade ago, cities like Beijing, Tianjin, and Hebei were among the most polluted in the world. Following international outrage and domestic unrest over deteriorating air quality, the Chinese government launched an aggressive clean-up campaign in 2013 under the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan. The plan included strict limits on coal consumption, mandatory upgrades to industrial technology, relocation of polluting factories, and a massive investment in public transportation and renewable energy. By 2020, PM2.5 levels in Beijing had dropped by over 35 percent. Crucially, the success hinged on centralized coordination, real-time air quality monitoring, and transparent data reporting, all enforced through a combination of fiscal penalties and incentives.

India, despite facing many of the same constraints as Pakistan, has made incremental progress through legal and technological reforms. The National Clean Air Programme, launched in 2019, aims to reduce PM2.5 and PM10 levels by 20 to 30 percent by 2024 in over 120 non-attainment cities. While the program has faced criticism for lacking enforcement strength, it has led to improvements in emissions data collection and city-level planning. The Indian judiciary has played a key role, issuing binding orders to regulate brick kilns, crop burning, and vehicular emissions. Delhi’s Odd-Even vehicle policy, while temporary, helped demonstrate the impact of demand-side interventions in reducing smog levels during peak pollution seasons. Additionally, India’s expansion of electric vehicle incentives and transition to cleaner fuel standards show that technological shifts are possible with government backing.

Indonesia has taken a regionally coordinated approach to pollution caused by forest fires and agricultural burning. The country has developed satellite-based fire monitoring systems and enacted laws that hold companies accountable for illegal land clearing. Through a combination of enforcement and community-led reforestation programs, provinces such as Riau have seen a reduction in fire hotspots. Importantly, Indonesia’s government has embraced public-private partnerships in deploying green infrastructure and renewable energy, allowing it to make progress even with limited public sector capacity.

These examples highlight a few critical patterns that are directly relevant to Pakistan. Strong regulatory frameworks must be backed by real-time data systems. Public access to environmental data in China and India has increased pressure on polluters and empowered citizens. Pakistan’s current lack of transparency in environmental reporting prevents similar civic engagement. Successful models combine punitive and incentive-based mechanisms. While fines and shutdowns are necessary for egregious violations, industries must also be given access to cleaner technologies, low-interest loans, and training programs to upgrade operations. Sub-national actors such as municipal governments, provincial courts, and civil society organizations must be empowered. Local-level governance has been central to India’s city-specific clean air plans and Indonesia’s fire prevention strategies.

For Pakistan, full replication of these models may be unrealistic given institutional limitations and fiscal constraints. However, several elements are adaptable. The establishment of a national smog emergency framework modeled on India’s approach could formalize city-specific mitigation targets. Public-private partnerships could fund low-cost air quality sensors in urban areas to expand the environmental monitoring network. A Clean Industry Transformation Fund could be introduced to assist brick kiln owners, steel manufacturers, and other high-emission sectors in transitioning to cleaner practices. Provincial governments, which already hold responsibility for environmental regulation under the 18th Amendment, can adopt mandates for pollution reporting, emissions caps, and interdepartmental coordination.

What unites all successful pollution mitigation efforts is not wealth or technological advancement alone, but sustained political will and a recognition that clean air is essential for development. With the right structure, Pakistan can adopt these lessons not as distant ideals, but as urgent blueprints tailored to its own social, environmental, and economic landscape.

A Path Forward: National Action Plan for Clean Air

Addressing Pakistan’s air pollution crisis requires more than isolated, short-term measures. It demands a comprehensive, integrated national strategy designed around specific targets, measurable outcomes, and coordinated implementation. A well-structured National Action Plan for Clean Air, backed by political commitment, institutional reform, and public support, can transform the country’s environmental trajectory and set the foundation for sustained growth and public health improvements.

At the core of this national plan should be the modernization and expansion of public transportation. Investments in affordable, efficient mass transit systems, particularly in heavily polluted urban centers like Lahore, Karachi, Faisalabad, and Peshawar, can significantly reduce vehicular emissions. Evidence from other developing countries suggests that accessible and reliable public transport can decrease private car usage by as much as 20 percent, lowering emissions and easing congestion. Cities should integrate bus rapid transit (BRT) networks, electric buses, and expanded metro rail lines into their urban planning to offer viable alternatives to private vehicles.

As seen in Taiwan, electric scooters compared to gas-powered motorbikes could be a small step in the right direction.

Electric vehicles (EVs) offer another key solution. The government should accelerate the transition to EVs through targeted incentives, subsidies, and infrastructural investments. Reducing import duties and taxes on electric vehicles and their components, establishing charging station networks, and implementing procurement policies that prioritize EVs for government and public fleets could catalyze rapid adoption. Global trends indicate that EV adoption substantially decreases local air pollutants, reduces fuel import dependence, and supports long-term sustainability.

As shown by the engineering marvel that is Tarbela Dam, clean energy should be a large part of Pakistan’s path forward.

Renewable energy expansion is essential to addressing pollution at its source. Currently, Pakistan generates roughly 60 percent of its electricity from fossil fuels. Transitioning rapidly to solar, wind, and hydropower will drastically reduce particulate emissions and carbon dioxide output. Pakistan’s untapped renewable potential, estimated at over 100,000 megawatts for solar and wind combined, offers an enormous opportunity. The government can foster this transition through public-private partnerships, feed-in tariffs, and targeted financial support mechanisms, helping industries and consumers adopt renewable technologies quickly and affordably.

Robust industrial regulation is equally critical. Policymakers must introduce clear, enforceable standards for industrial emissions and resource efficiency. This includes mandating cleaner production methods, installing pollution control devices, and shifting to low-emission industrial technologies, especially in high-impact sectors such as brick manufacturing, cement production, textiles, and steel manufacturing. To ensure compliance, regulatory agencies should be adequately funded and empowered to carry out regular inspections, impose meaningful penalties, and reward compliance through public recognition and financial incentives.

Public awareness and behavioral change campaigns must underpin these policy initiatives. Engaging the public through sustained, data-driven information campaigns about the health and economic benefits of cleaner air will build support for tougher regulations. Educational initiatives in schools, community outreach programs, and targeted messaging through social media can help reshape behaviors around waste disposal, vehicle usage, and energy consumption. Citizens informed about air quality data, pollution impacts, and their role in improving the environment can act as vital advocates for policy enforcement and compliance.

Industry incentives, zoning reforms, and environmental taxation also represent key policy tools. Economic incentives such as tax breaks, subsidies, and low-interest loans for adopting green technologies can help industries and small businesses transition to sustainable practices. Zoning reforms, including designated industrial zones separated from residential and agricultural areas, can reduce localized pollution exposure. Environmental taxes, such as carbon taxes or pollution levies, can further incentivize businesses to minimize emissions, while revenue generated from these taxes can finance clean-air initiatives.

A National Action Plan for Clean Air is ambitious but achievable. With clear policy frameworks, accountable institutions, and informed public engagement, Pakistan can significantly reduce air pollution, enhance public health, and strengthen economic resilience. Success hinges not only on technical solutions but also on a collective shift in priorities and values, recognizing clean air as fundamental to the country’s future development and prosperity.

Local Solutions, National Vision

While national policy frameworks are critical, Pakistan’s journey toward cleaner air and environmental sustainability will largely depend on actions taken at local levels. City governments, community organizations, and educational institutions must become key drivers of meaningful, ground-level change. Local governments hold considerable influence over urban planning, transportation management, and waste disposal practices. By prioritizing urban planning strategies such as establishing green belts around cities, enforcing strict zoning laws that separate industrial and residential areas, and implementing pollution taxes to discourage harmful practices, municipal authorities can significantly mitigate air pollution. These local actions not only immediately improve air quality but also create healthier, more livable cities capable of supporting sustainable growth.

Civil society organizations play an equally vital role. Non-governmental organizations, environmental activists, and community groups can help bridge gaps in government action by promoting awareness, accountability, and citizen participation. Grassroots initiatives can amplify pressure for policy enforcement, educate communities about sustainable practices, and organize collective responses to pollution episodes. Universities and research institutions can support these efforts by providing the necessary scientific data, analysis, and innovation required for informed decision-making. Through community-driven air quality monitoring programs and collaborative research, local institutions can generate valuable real-time data, enhance public engagement, and foster evidence-based policy interventions.

Pakistan’s young population is key to bringing forth change.

Youth-led initiatives can further energize the movement for cleaner air. Pakistan’s young population, comprising over 60 percent of the country’s demographic profile, is well-positioned to champion sustainability through digital activism, community outreach, and innovative entrepreneurial solutions. Empowering young leaders through education, funding, and platforms for advocacy can create a generational shift in attitudes toward pollution and environmental protection, laying the foundation for lasting societal change.

Strategic Framing: Pollution as a National Security Issue

Recognizing pollution merely as an environmental or health concern understates its broader implications for national security. Unchecked pollution erodes human capital, weakening a nation’s core asset—its population. Chronic illnesses linked to poor air quality reduce workforce productivity, increase healthcare expenditures, and limit the educational attainment of younger generations. Over time, these cumulative effects undermine economic stability, creating vulnerabilities that extend well beyond immediate health crises. The degradation of human capital thus becomes a national security issue, directly affecting Pakistan’s economic competitiveness and stability.

Additionally, pollution exacerbates social inequalities, aggravating political tensions and fueling instability. Marginalized communities, disproportionately affected by toxic environments, can lose faith in governance systems unable to protect their basic rights. Such grievances may lead to social unrest and political disengagement, undermining broader governance and security efforts.

Therefore, framing clean air as a fundamental human right rather than a luxury is essential. Ensuring breathable air must be treated with the same strategic urgency as national defense and energy security. When policymakers begin to view environmental sustainability through a national security lens, clean air initiatives gain stronger political backing and budgetary priority. Protecting citizens from pollution becomes a central pillar of governance, reinforcing national resilience, economic stability, and public trust.

A Breathable Future

Pakistan stands at a critical juncture. The severity of the pollution crisis, with its profound implications for public health, economic stability, environmental sustainability, and national security, demands immediate and decisive action. Air pollution is no longer merely an inconvenience or seasonal nuisance, it is a deeply embedded structural threat with far-reaching consequences.

Throughout this analysis, several core arguments have emerged clearly. First, pollution exacts an immense human cost, directly shortening lives and weakening the nation’s health infrastructure. Second, pollution imposes substantial economic losses, limiting productivity, depressing agricultural output, harming education, and deterring foreign investment. Third, the pollution crisis intersects deeply with broader environmental and climate challenges, magnifying water scarcity and ecological degradation. Fourth, significant institutional and policy gaps currently hinder meaningful progress, necessitating a renewed commitment to environmental governance. Fifth, successful global examples from China, India, and Indonesia demonstrate practical pathways for Pakistan, emphasizing the value of transparent data systems, targeted regulations, and local-level enforcement. Lastly, addressing pollution effectively requires combined local and national strategies, public engagement, youth mobilization, and a clear strategic vision framing clean air as a national priority.

There is a profound moral imperative driving this agenda. Clean air should never be an exclusive privilege but a universal right, fundamental to human dignity and societal well-being. It is incumbent upon policymakers, institutions, and citizens alike to reject normalization of this crisis and instead rally around sustainable, actionable solutions.

Looking ahead, this report sets the foundation for deeper explorations into related environmental challenges, including water pollution, waste management, and climate resilience. Future Indus Policy Forum reports will delve into these interconnected issues, providing comprehensive analysis, actionable strategies, and sustained advocacy toward a cleaner, healthier, and more secure Pakistan. The stakes are clear, the urgency undeniable, and the opportunity immense. Securing a breathable future is achievable, and it begins with decisive, collective action now.