True national security does not begin on the battlefield. It begins long before conflict erupts, in the strength and resilience of a nation’s economy. It begins with the ability to feed one’s population, fuel one’s industries, sustain one’s logistics, and manufacture one’s own essential goods. Without these capabilities firmly in place, no army, no matter how motivated or well-equipped, can survive the harsh realities of modern warfare.

Pakistan today stands at a critical juncture. While it maintains a large standing military, the foundations upon which any future conflict would be fought are dangerously fragile. The economy is heavily reliant on imports that the country cannot sustainably afford, particularly in energy, food, and industrial inputs. The nation runs persistent trade deficits, has shallow industrial depth, and lacks the logistical resilience necessary to support a long or even medium-term conflict. An army is an inherent drain on national resources. It consumes manpower, energy, and capital without producing economic value in return. Sustaining a modern army therefore requires an economy that is not only strong, but also diverse, independent, and deeply integrated into the global system on its own terms.

Pakistan must fundamentally rethink its approach to economic development. Rather than continuing to rely on imports, the country must pursue a strategy of producing domestic equivalents for as many economic goods as possible. This is not just a matter of pride or symbolism. A strong domestic industrial base creates jobs, strengthens human capital, fosters innovation, and, most critically, allows a nation to earn foreign exchange by offering valuable products to the world. Trade must be two-sided; Pakistan must strive to export high-value goods that others want to buy, not simply rely on imported consumption funded by loans and remittances. Without this shift, the economy will remain brittle, and national security will remain permanently compromised.

According to the OEC, Pakistan’s exports per capita are valued only at $145.

Effective use of labor is also a core component of this transformation. In a modern economy, labor must be directed toward activities that create tangible economic output. Traditional forms of employment that offer no real contribution to productivity, such as domestic servitude or redundant bureaucratic positions, must be phased out. Every citizen must become an active participant in building the nation’s economic strength, whether through industry, agriculture, energy, or innovation. A society where the majority of labor is tied up in non-productive sectors cannot build the economic surplus necessary to support either upward mobility or sustained national defense.

Energy independence will be another defining pillar of true security. Pakistan today cannot survive long without importing natural gas and oil. Natural gas forms the backbone of Pakistan’s electricity production, industrial processes, and urban heating systems. Oil powers transportation, agriculture, and much of the logistics backbone. In the event of a full-scale conflict or international isolation, energy imports would halt almost immediately due to soaring insurance costs, blockade risks, and diplomatic pressure. Without immediate domestic replacements, Pakistan’s economy would grind to a halt within weeks. Nuclear, hydroelectric, and renewable energy sources must therefore be expanded aggressively to provide a resilient, internal foundation for the national grid.

Food security presents an equally urgent challenge. Despite being an agricultural country by tradition, Pakistan remains dependent on the import of wheat, pulses, edible oils, and other staples. In wartime or crisis conditions, the inability to secure consistent food supplies would lead to famine, unrest, and a collapse of national morale. A country can field the bravest soldiers in the world, but without full stomachs and steady supplies, even the most determined forces will eventually wither away.

37% of Pakistan’s population remains food insecure, a number which could skyrocket in the event of conflict.

No amount of bravery can overcome the hard realities of hunger, empty fuel tanks, or a broken industrial system. Logistics are the true lifeblood of a military, and logistics are inseparable from the health of the national economy. Without factories producing spare parts, without mines providing critical raw materials, without farms feeding the civilian and military population, no army can survive for long. Motivation alone cannot carry a country through a modern conflict. It must be backed by real material strength.

Pakistan must therefore view economic reform not as a separate, peacetime concern, but as a core part of its strategy. Building a resilient economy will not only raise the standard of living for its citizens, offering them greater opportunities and dignity, but will also ensure that the nation can withstand the pressures of the future.

If Pakistan is to secure its sovereignty in the twenty-first century, it must first win the battle for economic resilience. Every mine opened, every factory built, every new farm cultivated, and every skilled worker trained is a step toward real national strength. Only by building these foundations in peacetime can Pakistan hope to prevail when it matters most.

Pakistan’s Critical Vulnerabilities in a Time of Conflict

At the heart of any nation’s security lies its ability to survive independently, or at least semi-independently, in times of crisis. For Pakistan, this remains a distant goal. Beneath the surface of military strength lies an economy and logistical system dangerously exposed to disruption, sanctions, or sustained conflict.

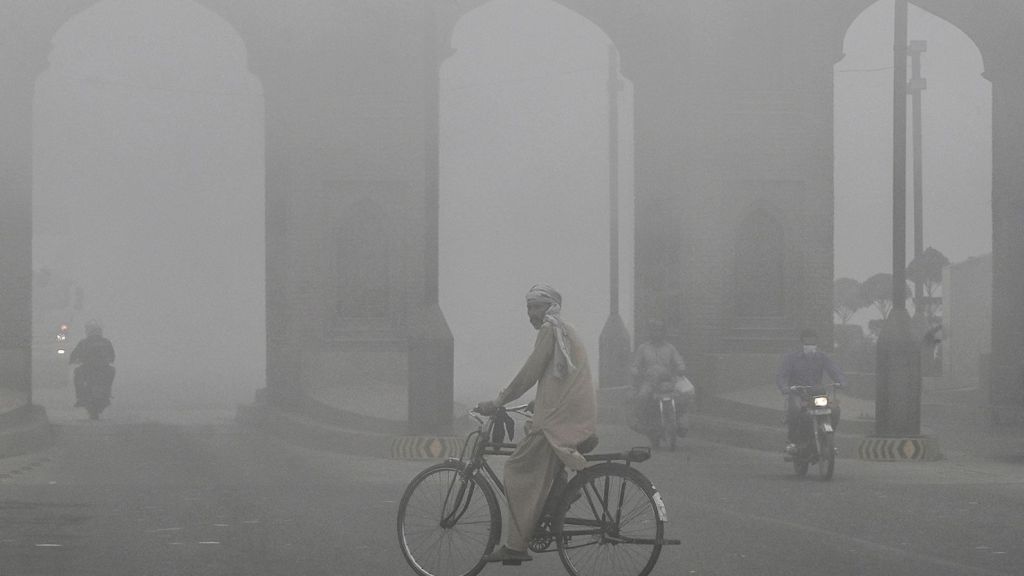

Today, Pakistan remains overwhelmingly reliant on critical imports to maintain even basic civilian and military functions. In 2023, total imports stood at approximately 55 billion USD, while exports hovered around 30 billion USD, creating a deep and persistent trade deficit. Energy alone accounted for over 23 billion USD of imports, representing more than 40 percent of Pakistan’s foreign currency expenditures. Over 80 percent of Pakistan’s crude oil and oil products are imported. Natural gas, particularly liquefied natural gas (LNG), forms the backbone of industrial and electricity generation sectors, and roughly a third of Pakistan’s total gas consumption is imported.

There is little domestic redundancy to cushion any major supply shock. Pakistan possesses no significant strategic petroleum reserve, nor can it quickly pivot to alternative energy sources if fuel imports are cut off. Even a partial disruption in maritime energy imports would trigger nationwide blackouts, cripple transport networks, and paralyze both civilian life and military logistics.

Agriculture, though a traditional strength, offers little real security. Despite being one of the world’s largest producers of wheat and rice, Pakistan imported over 2.5 million metric tons of wheat in 2022 to manage domestic shortages. Dependency on imported fertilizers, pesticides, and modern farming equipment only deepens this vulnerability. In a conflict scenario that disrupts shipping or isolates Pakistan financially, food insecurity would rapidly become a national emergency.

Pakistan’s agricultural sector is dependent on imported fertilizers, pesticides, and equipment.

Manufacturing and industrial output are also deeply compromised by import dependency. Pakistan’s textile sector, responsible for over 60 percent of export earnings, relies heavily on imported cotton, dyes, chemicals, and advanced machinery. Heavy industries such as steel production depend on imported iron ore, coal, and specialized parts. Pakistan’s automobile assembly plants, often touted as evidence of industrial progress, largely consist of imported kits assembled domestically with minimal local content. High-value sectors such as semiconductors, precision engineering, aviation technology, and pharmaceuticals remain almost entirely absent or dependent on foreign inputs.

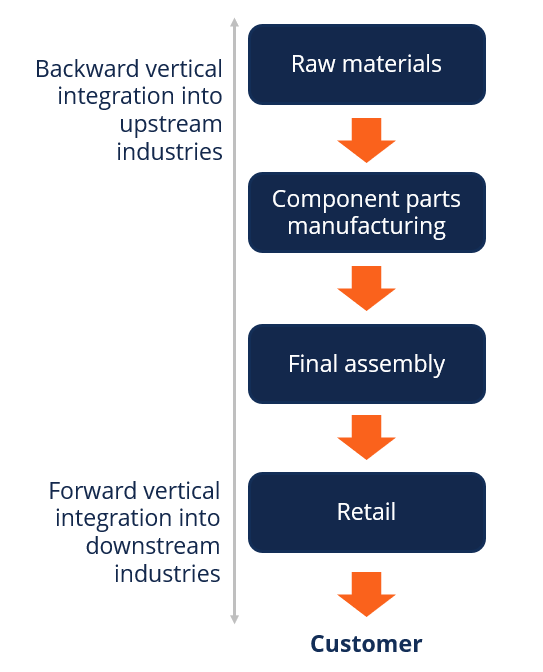

This lack of vertical integration, the ability to control the full supply chain from raw material to finished product, means that even if Pakistan maintains nominal factories and production lines, they would be useless without constant imports of parts, chemicals, energy, and expertise. In a conflict, these critical supply lines would be the first targets for disruption by an adversary, or could collapse under the pressure of sanctions and global financial isolation.

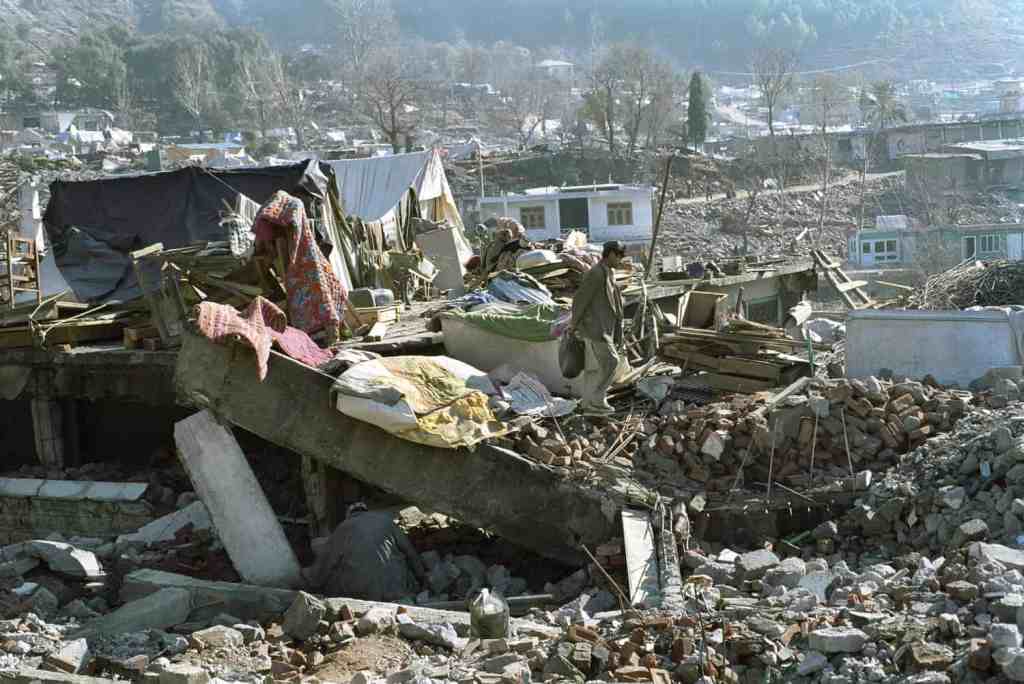

Pakistan’s logistical vulnerabilities further magnify the problem. Over 90 percent of all imports and exports pass through just two major ports: Karachi Port and Port Qasim. Gwadar Port, while strategically located, is underdeveloped and lacks the handling capacity to meaningfully relieve the pressure on Karachi and Port Qasim. These ports are easy targets for blockade, missile strikes, or sabotage, and the national economy has no credible redundancy to absorb their loss. Containers would face increased insurance rates due to the conflict, if shipped at all, which could make necessities unaffordable.

Pakistan’s imports are extremely vulnerable in conflict. 90% of containers enter only through two ports.

Inland transportation networks are no better prepared. Pakistan’s railways, once a colonial-era asset, have deteriorated into a slow, inefficient, and unreliable system. Freight transport is heavily dependent on an overburdened road network that would quickly become choked under wartime conditions. There are no dedicated military or emergency logistics corridors, no parallel supply chains insulated from civilian traffic, and few options for rapid, mass-scale strategic mobility within the country.

Financial resilience is another critical vulnerability. Pakistan’s foreign currency reserves, as of early 2024, hover between 8 to 10 billion USD, barely enough to cover two months of imports. The country remains heavily reliant on remittances, which brought in around 27 billion USD in fiscal year 2023. These flows sustain domestic consumption and prop up foreign exchange reserves. A disconnection from the SWIFT international banking network, similar to sanctions imposed on other countries, would cripple Pakistan’s ability to receive remittances, conduct trade finance, or even pay for essential imports. The economy would face an immediate liquidity crisis, leading to mass shortages, runaway inflation, and a collapse of the national currency.

These vulnerabilities can be visualized through a “pyramid of national needs,” akin to Maslow’s hierarchy applied to state survival. At the base are energy security and food security—both currently import-dependent. Above that lies industrial autonomy, absent or shallow in Pakistan’s case. Above that rests financial sovereignty, deeply compromised by reliance on external debt, remittances, and foreign banks. Only at the very top does military capability emerge. Without securing the foundational layers, military strength becomes hollow, unable to function without constant external lifelines.

Even in the absence of war, the modern world’s complex, interconnected economies mean that political pressure, sanctions, or global market shocks could produce the same crippling effects as open conflict. A sudden disruption of oil supplies, an embargo on industrial parts, or the freezing of banking access could paralyze Pakistan’s economy in weeks, long before any military campaign could be mounted or defended against.

The reality is stark: Pakistan’s vulnerabilities are not hypothetical or distant risks. They are immediate, structural weaknesses embedded into the current national system. In a serious conflict or geopolitical crisis, Pakistan could find itself crippled not by battlefield defeats, but by economic and logistical collapse.

If Pakistan is to survive and thrive in an increasingly harsh international environment, it must begin by hardening its foundations. The first battles will be fought in peacetime, on factory floors, in energy fields, in banking systems, and on farms. If those battles are lost, no army will be able to hold the line when the real conflict comes.

Industry as the Engine of National Survival

If Pakistan is serious about securing its future, then economic reform must begin with industry. No modern nation can defend itself without a deep, resilient, and technologically capable industrial base. Industry is not only the backbone of civilian prosperity but also the silent strength that sustains military logistics, energy security, infrastructure repair, and technological innovation during times of conflict.

At present, Pakistan’s industrial structure is shallow and heavily dependent on foreign inputs. Textiles dominate exports, accounting for over 60 percent of total export value, yet even the textile sector relies heavily on imported cotton, dyes, chemicals, and machinery. Outside of textiles, Pakistan’s industrial landscape is dangerously thin. The country lacks strong domestic capabilities in advanced manufacturing, precision engineering, electronics, automotive components, aviation technology, and pharmaceuticals, sectors that define true economic and strategic strength in the modern world.

Pakistan must create vertically integrated specialized industries to create domestic alternatives to imports.

To move beyond this fragility, Pakistan must fundamentally reimagine its industrial base. It must diversify beyond low-margin, commodity industries such as raw textiles and basic agriculture, and aggressively build high-value manufacturing sectors. Precision machinery, semiconductors, specialized chemicals, automotive parts, industrial equipment, and medical devices must become national priorities. These industries generate higher export earnings, stimulate the growth of skilled labor, and create the vertically integrated supply chains necessary for strategic independence. Without such a shift, Pakistan will remain trapped in a cycle of exporting cheap goods while importing expensive necessities, forever vulnerable to external shocks.

True industrial strength requires controlling the full chain of production, from raw material extraction to final assembly. Pakistan today lacks this vertical integration. Industries are often dependent on imported components at every stage, meaning that even factories located on Pakistani soil would quickly fall silent if foreign suppliers cut off critical inputs. A credible industrial strategy must aim to develop domestic capabilities in metallurgy, petrochemicals, electronics fabrication, and machine tooling, allowing Pakistan to fabricate its own basic and advanced components at scale.

True industrial strength requires controlling the full chain of production, from raw material extraction to final assembly. Pakistan today lacks this vertical integration. Industries are often dependent on imported components at every stage, meaning that even factories located on Pakistani soil would quickly fall silent if foreign suppliers cut off critical inputs

None of this can happen without a revolution in human capital. Modern industries require a skilled workforce trained in engineering, technical trades, and scientific research. Pakistan must prioritize technical education, vocational training, and university-industry partnerships that align academic learning with real industrial needs. Producing graduates with theoretical knowledge but no practical skills will no longer suffice. Human capital development must be treated as a core national security issue, as important as acquiring fighter jets or building tank battalions.

Industrial growth cannot occur without reliable, abundant energy. Pakistan’s industries already suffer from rolling blackouts and energy shortages, which cripple competitiveness and discourage investment. To sustain any serious industrialization drive, Pakistan must massively expand its domestic energy production. Nuclear power, hydroelectric projects, and renewable energy must be developed alongside domestic natural gas extraction. Special industrial zones should be established where reliable energy, modern transport infrastructure, and tax incentives combine to attract both domestic and foreign investment.

The defense industry must also be treated as a strategic priority. While Pakistan has made progress with platforms like the Al-Khalid tank and the JF-17 fighter jet, critical vulnerabilities remain. The country still imports key technologies such as avionics, radar systems, and precision-guided munitions. Pakistan must expand its defense production to cover a wider range of military needs, including ammunition stockpiles, electronic warfare equipment, air defense systems, and drone technologies. Military production must happen on a scale sufficient not only to equip the armed forces under peacetime conditions, but also to allow for rapid expansion and replenishment in the event of a major conflict. Without industrial surge capacity, wars cannot be sustained.

Pakistan’s defense industry should avoid importing technologies and aim to foster development in house.

In this regard, Pakistan must strategically leverage its relationship with China. China offers not just access to equipment, but also a model for how a nation can rapidly build indigenous industrial strength through careful technology transfer, joint ventures, and disciplined domestic investment. Pakistan must move beyond simple procurement of Chinese systems and instead focus on extracting industrial knowledge, training a new generation of engineers and technicians, and localizing production to the greatest extent possible. Alliances are valuable, but they are most valuable when they serve as catalysts for building true self-sufficiency.

History offers a clear lesson. During World War II, the United States was able to fight and ultimately win a two-front war, not because it had the largest standing army at the outset, but because it had the strongest industrial base. American factories produced tanks, aircraft, ships, munitions, and supplies on a scale that no other nation could match. At the height of the war, the United States was producing over 50,000 aircraft per year and launching a fully equipped Liberty cargo ship every few days. Victory came not from sheer military numbers alone, but from the ability to replace losses faster than the enemy could inflict them, to sustain long campaigns across oceans, and to keep civilian society functioning while fighting abroad.

During World War II, the United States was able to fight and ultimately win a two-front war, not because it had the largest standing army at the outset, but because it had the strongest industrial base

Pakistan must absorb this lesson. In the modern era, wars are not won solely by tactical brilliance or isolated battlefield victories. They are won by economies that can endure, adapt, and outlast. Industrial power is not a luxury for a nation seeking security. It is the foundation upon which all true military and political strength is built.

The battles of tomorrow will not only be fought with rifles and tanks, but with assembly lines, research laboratories, and export contracts. If Pakistan is to truly defend its sovereignty, it must stop being merely a market for foreign goods and become the builder of its own destiny.

Real Strength Begins with Resilience

A military, no matter how large or capable, is only one part of a nation’s power. History has repeatedly shown that wars are not won by armies alone. They are won by nations that can feed their people, fuel their industries, sustain their logistics, and adapt under pressure. Without these foundations, even the bravest armies will eventually falter.

Pakistan today faces vulnerabilities that cannot be fixed by acquiring more weapons or expanding the size of the armed forces. It faces vulnerabilities rooted in its economy, its industrial capacity, its energy security, and its financial independence. A fragile economy will produce a fragile defense. A nation that cannot manufacture its own critical goods, power its industries independently, or feed its own population cannot hope to endure the sustained pressures of modern conflict.

But this challenge also represents an opportunity. Building a resilient economy is not only a matter of national defense. It is the foundation for a higher quality of life for all citizens. Nations like South Korea and Taiwan provide clear examples. Both nations invested heavily in building strong, diversified economies capable of producing high-value goods, fostering innovation, and integrating into the global market on their own terms. As a result, they have developed militaries that are respected and capable, but more importantly, they have built societies where citizens enjoy high standards of living, broad educational opportunities, strong healthcare systems, and economic dignity.

Pakistan must learn from nations such as South Korea, where economic and military strength are intertwined.

The lesson is clear. National security and national prosperity are not separate goals. They are two sides of the same coin. A strong economy gives a nation not just the tools to defend itself, but the ability to uplift its people, to create opportunities, and to secure its sovereignty through strength rather than dependence.

If Pakistan truly seeks to secure its future, it must begin by securing its economic foundations. It must build industries that can produce, innovate, and compete. It must invest in energy, education, infrastructure, and research. It must create a system where every citizen becomes a contributor to national resilience, not merely a bystander.

The first battles are fought in boardrooms, laboratories, mines, farms, and factories. They are fought in the quiet decisions made in peacetime that determine whether a nation will endure when times turn dark. Real strength begins with resilience. Real independence begins with self-sufficiency.