Pakistan today stands at a crossroads, caught between borrowed institutions and an unclaimed inheritance. In its pursuit of modernity, the country continues to rely on the structural remains of British colonialism. The military still operates with a colonial mindset. It is centralized, insulated in defense colonies, and more suited for control than defense. The bureaucracy follows outdated British systems designed for a foreign empire’s dealing with the locals, not for service to the people. Culturally and politically, the elite often mimic the West rather than reflect the region’s own traditions. The result is a state that feels foreign to its own people, uncertain of who it is or who it wants to be.

But Pakistan does not need to invent a new identity. Nor should it continue to wear the garments of a colonial past. What it needs is to recognize and embrace the civilizational legacy it was born into. For over a thousand years, Muslims in the Indian subcontinent built empires that led in science, architecture, military strategy, poetry, education, and governance. From the Delhi Sultanate to the Mughals, they ruled vast territories and created a cultural and political tradition that influenced the world. This is the tradition Pakistan has the right to inherit, but so far has failed to claim.

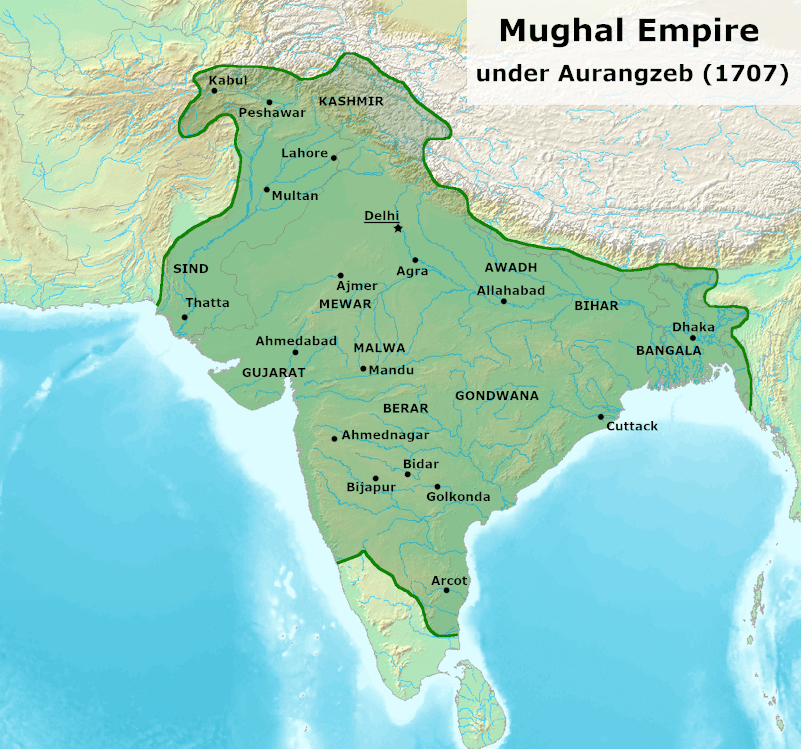

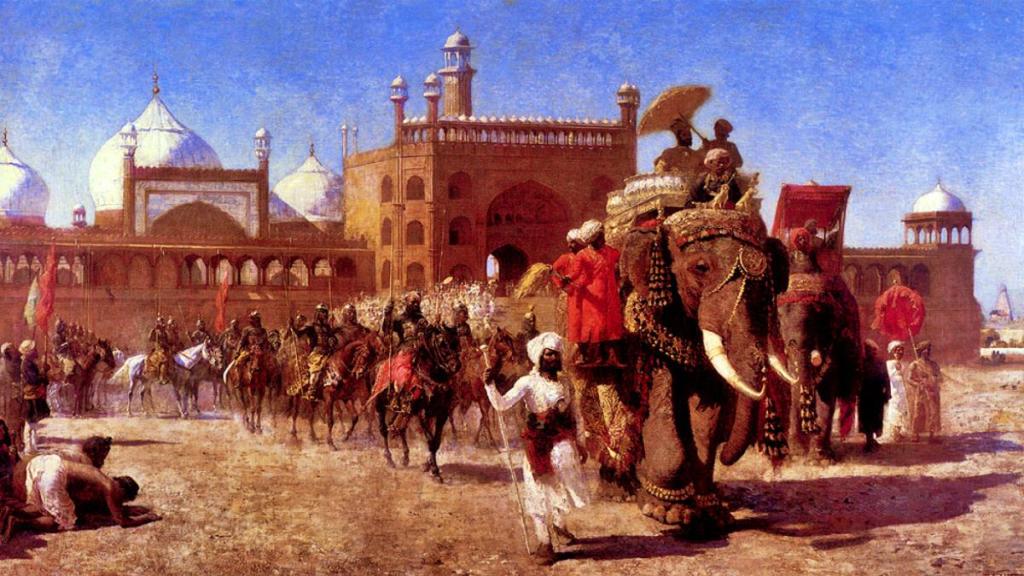

The Mughal Empire spanned across the entire subcontinent as a beacon of science, architecture, military strategy, poetry, education, and governance.

Modern Pakistan behaves less like the descendant of great empires and more like a confused postcolonial experiment. It imitates Western structures without possessing Western power, and in doing so loses sight of what makes it unique. This identity crisis weakens the state from within. A nation without confidence in its own history and values cannot build lasting institutions or inspire future generations.

Pakistan should not think of itself as a country born in 1947 but as the modern continuation of a rich and enduring Muslim presence in South Asia. That identity is not rooted in slogans or nostalgia, but in real achievements that shaped the subcontinent for centuries. The Koh-i-Noor in the British crown is a reminder, both literal and symbolic, of how valuable this region once was. Pakistan does not need an empire, but it does need dignity. It needs to draw from the strength of its civilizational past to chart a future that is grounded, authentic, and sovereign.

The Koh-I-Noor, the Crown Jewel of Queen Elizabeth, originates from the Mughal Peacock Throne in Delhi. A symbol for how valuable this region once was.

Only then can Pakistan begin building a future with direction, purpose, and pride.

Reclaiming a Civilizational Inheritance: Why Pakistan Must Embrace the Legacy of Muslim India

Before modern-day Pakistan and India became symbols of poverty, corruption, and disarray in the global imagination, the Indian subcontinent was the seat of some of the most powerful and wealthy Muslim empires in the world. From the early days of the Delhi Sultanate in the 13th century to the height of the Mughal Empire in the 17th, Muslim rule in India represented a golden age of political power, cultural brilliance, and economic prosperity that rivaled and at times exceeded its European and Asian contemporaries.

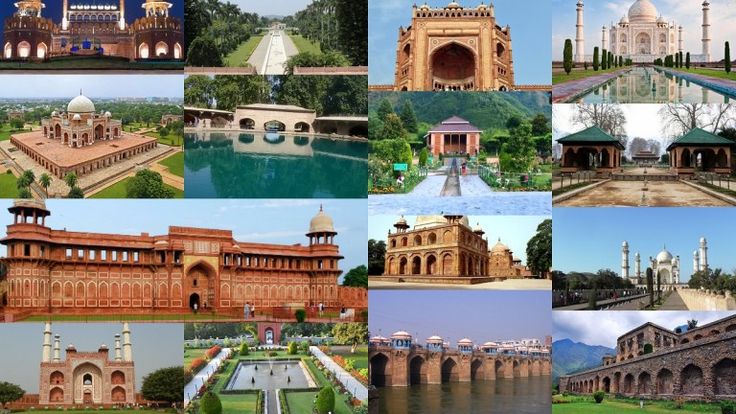

Mughal architecture in the subcontinent demonstrates the empire’s prowess.

The Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526) laid the foundation for centuries of Muslim rule in the subcontinent. Led by dynasties such as the Mamluks, Khiljis, Tughlaqs, and Lodis, these rulers were skilled administrators, warriors, and builders. They introduced advanced military strategies, expanded infrastructure, and developed one of the earliest centralized administrations in South Asia. Cities like Delhi became hubs of power, trade, and learning, attracting scholars, merchants, and artisans from across the Islamic world.

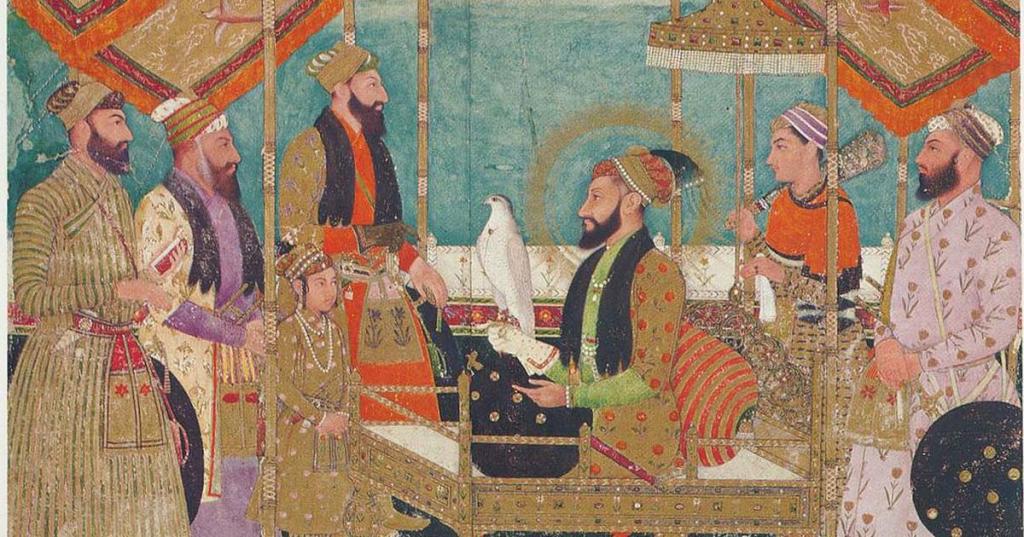

Then came the Mughals. From Babur’s conquest in 1526 to the reign of Aurangzeb in the late 1600s, the Mughal Empire emerged as one of the most formidable and wealthy empires on Earth. At its peak under Emperor Akbar and his successors, it ruled over 150 million people, more than any European state at the time. The empire boasted one of the world’s largest and most professional standing armies. It collected enormous revenue through a sophisticated taxation system and maintained a thriving trade network that connected Central Asia, the Middle East, and Europe.

Shah Jahan and the Mughal Army return after attending a congregation in the Jama Masjid, Delhi.

The subcontinent was not just wealthy, it overflowed with treasures. Cities like Lahore, Agra, Delhi, and Fatehpur Sikri glittered with riches, palaces, gardens, and centers of learning. The Mughal treasury funded enormous architectural projects that still stun the world today: the Taj Mahal, Humayun’s Tomb, Shalimar Gardens, the Badshahi Mosque, the Red Fort. These were not merely monuments; they were symbols of confidence, dignity, and grandeur. Even today, they stand tall as reminders of what this region once was—a beacon of culture and civilization.

The Indo-Islamic architectural projects that span across the subcontinent demonstrate what this region once was, a beacon of culture and civilization.

These Muslim empires were not weak, divided, or desperate. They defended their frontiers with courage and discipline. They projected strength abroad and enforced stability at home. Justice, law, and learning were central to their rule. Institutions like madrasas and courts helped organize society around Islamic legal and moral values. The high culture that developed, from Urdu poetry to miniature painting, from Indo-Persian music to culinary traditions, was not only influential across Asia but deeply rooted in the everyday lives of the people.

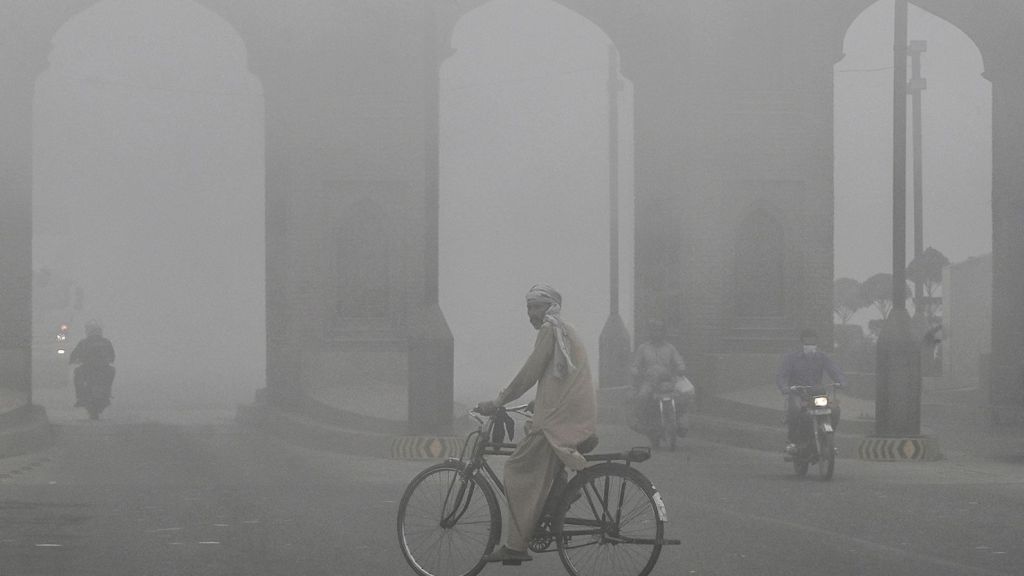

This was a time when being from Muslim India carried prestige. Diplomats, travelers, and traders came from Europe, Persia, and the Ottoman Empire to witness its splendor. Foreign merchants flocked to its ports and cities, eager to buy its textiles, spices, and jewels. And despite internal rivalries and eventual decline, these empires maintained a degree of power and respect that modern Pakistan can only look back on with longing.

Foreign merchants flocked to the subcontinents ports and cities, eager to buy its textiles, spices, and jewels.

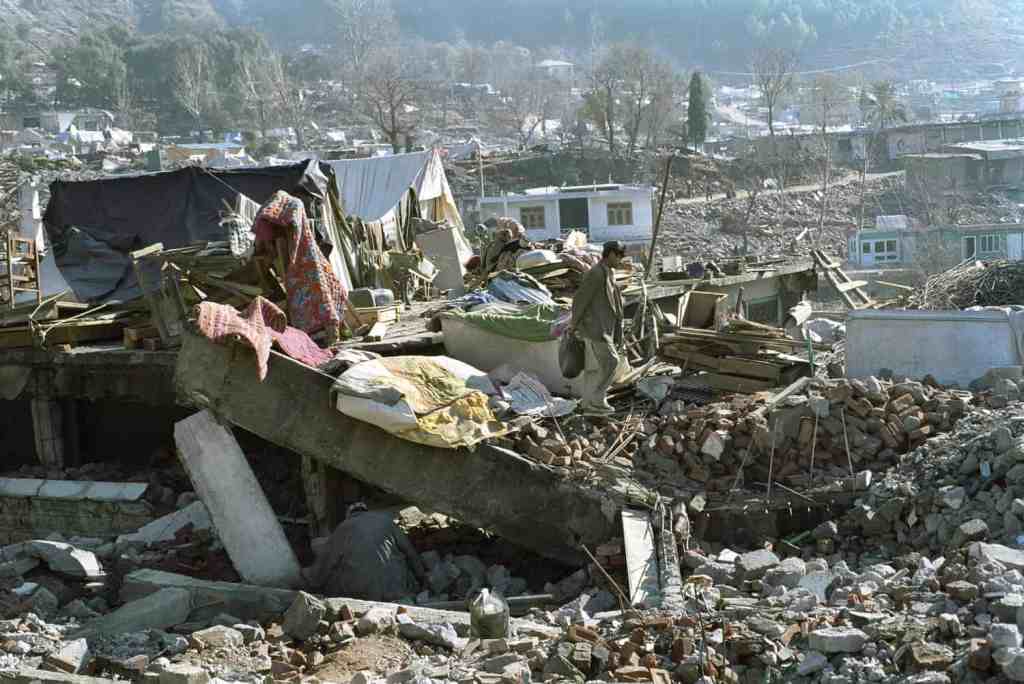

The tragedy is not just that this legacy has been forgotten, but that it has been actively abandoned. Today, the lands once ruled by these empires are riddled with poverty, political instability, and dependence on foreign aid. Modern Pakistan in particular has distanced itself from this glorious inheritance. Rather than building upon the strength, dignity, and beauty of its Muslim past, it has become trapped in a colonial mold that was never meant to serve a free and sovereign people.

The question now is not whether this legacy can be reclaimed, as it must be. If Pakistan wishes to rise with dignity, it must first remember what it once was. That memory, and the civilizational depth it represents, is the foundation for any meaningful rebirth.

The Modern Crisis: Disunity, Mismanagement, and the Failure of the Colonial State Model

Despite its immense historical inheritance, Pakistan today is a country adrift. Its administrative, economic, and military institutions are relics of colonial design, ill-suited to the needs of a modern, sovereign Muslim society. The disunity and dysfunction that plague the state are not rooted in cultural or geographic diversity, but in the failure to build a system that draws strength from that diversity.

Pakistan’s very outline bears colonial fingerprints, drawn by a British judge unfamiliar with the region he reshaped forever via the Radcliffe line. Radcliffe has never travelled east of Paris.

In pre-modern times, long before the advent of railways, highways, or the internet, Muslim rulers in the subcontinent managed to govern vast territories with relatively high cohesion. The Mughal Empire, for instance, maintained links between Bengal, Kashmir, the Deccan, and Kabul through a combination of localized governance, cultural integration, and a shared administrative and legal framework rooted in Islamic principles. In contrast, modern Pakistan, a geographically smaller state with access to advanced technology, struggles to keep its regions meaningfully connected. Balochistan, Sindh, southern Punjab, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa all remain politically and economically marginalized, often treated as peripheral zones rather than integral parts of a unified nation.

This disconnection is not logistical. It is ideological and institutional. The country’s governing model, inherited wholesale from British colonialism, was never meant to empower or integrate. It was meant to extract and control. Today’s bureaucracy is bloated, unaccountable, and slow. It delays even basic services, suffocates innovation, and breeds corruption. Policies are reactive rather than visionary, and development projects often serve elite interests rather than public needs. Pakistan is not poor because it lacks resources or talent. It is poor because it lacks competent governance.

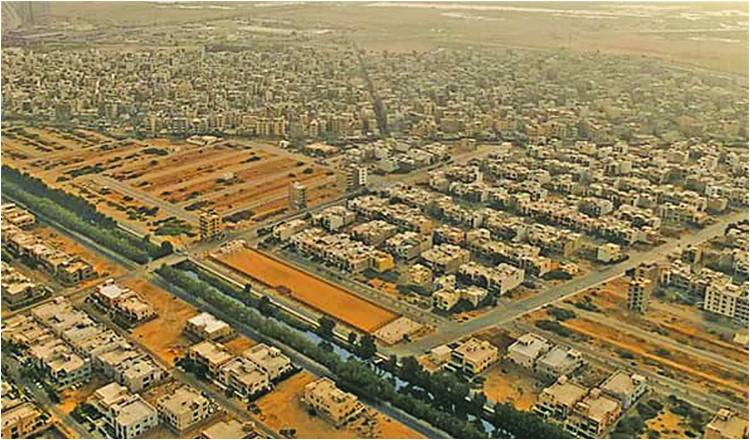

Nowhere is this dysfunction more apparent than in the military’s role in national life. Rather than serving as a protector of the people, Pakistan’s military establishment has become a parallel state. It builds gated communities, controls vast economic enterprises, and lives physically and psychologically removed from the citizens it claims to defend. The separation between the military elite and the general public weakens national cohesion and fuels resentment, especially when military leaders enjoy foreign luxuries while ordinary citizens face blackouts, inflation, and failing public services.

The Defense Housing Authority (DHA) demonstrates the parallel society created within the nation.

The very concept of a large, permanent standing army is a Western import rooted in colonial and imperial warfare. It is both economically burdensome and socially alienating. Historically, Muslim societies, including the armies led by the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), relied on a smaller core of trained fighters, with the broader population mobilized only in times of need. This approach allowed societies to maintain agricultural, economic, and intellectual productivity during peacetime. Men farmed, studied, built businesses, and raised families. When war called, they responded.

Modern Pakistan, by contrast, diverts a massive portion of its limited budget to maintaining a peacetime force that does not generate economic value. Young, healthy men are locked into a profession that often distances them from the public and limits their contributions to broader nation-building. A smarter approach would be to maintain a lean, elite force capable of training and commanding a larger volunteer force if and when required. This would reduce the economic drain while preserving military readiness and allowing the population to remain integrated and productive.

Even beyond the military and bureaucracy, the overall pace of national life in Pakistan is excruciatingly slow. From court proceedings that take decades to be resolved to infrastructure projects that stall for years, inefficiency is normalized. Talented individuals are stifled by red tape, nepotism, and a lack of clear direction. Innovation is rare not due to a lack of intellect, but because the system does not reward merit, experimentation, or independent thinking.

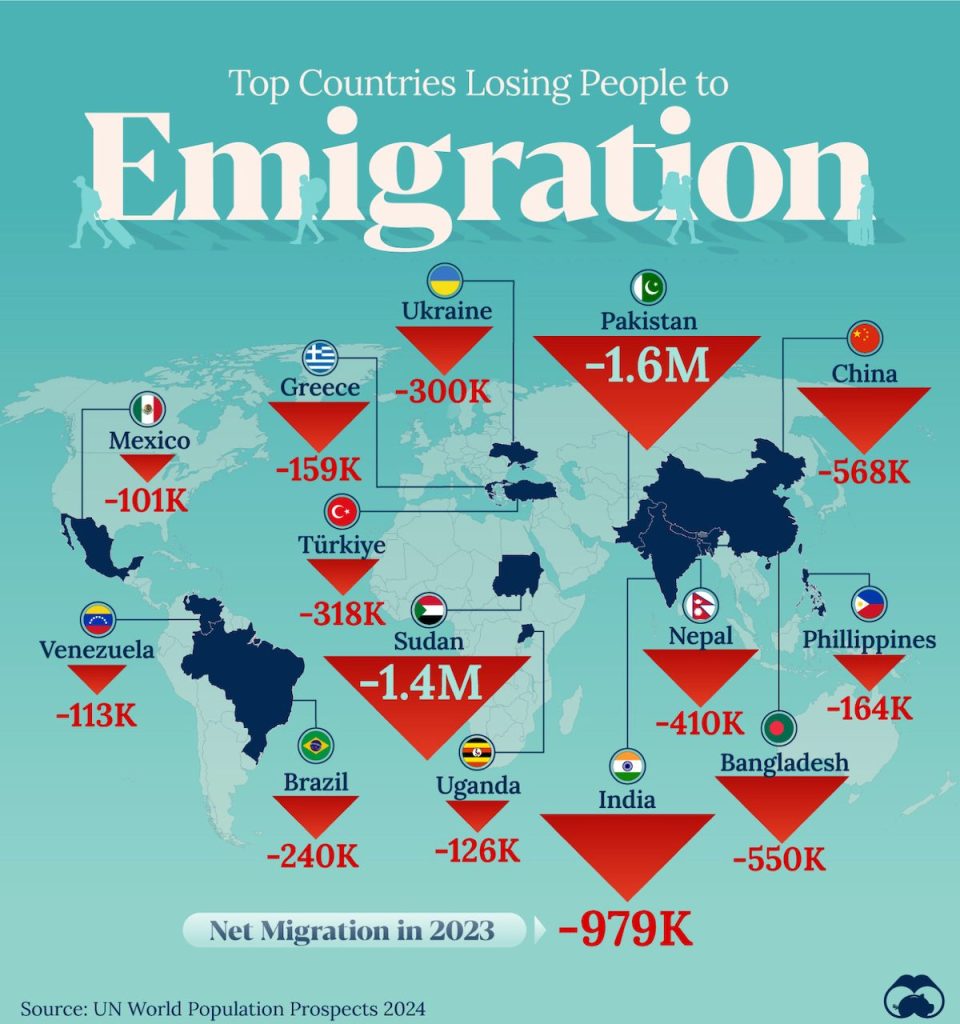

Pakistan lost 1.6 million people to emigration in 2024. The number speaks for itself.

Pakistan has reached a point where mere reform is not enough. What is needed is a structural and philosophical rethinking of the state. The colonial state model was never built to nurture an Islamic society or reflect Muslim values of justice, consultation, and social cohesion. It was built to manage subjects. As long as Pakistan clings to this outdated model, it will remain slow, disconnected, and weak.

If Pakistan is to survive, let alone thrive, it must do more than tinker with policy. It must undergo a civilizational awakening—a conscious effort to reconnect with the deep roots of Muslim India and the even older civilizations that once flourished on this land. This is not a call for romantic nostalgia. It is a demand for national clarity, institutional realignment, and the restoration of public dignity through meaningful reform. Civilizations are not just born—they are remembered, revived, and rebuilt.

The first step is ideological. Pakistan must abandon the colonial mindset. This means dismantling the British-imposed bureaucratic and military models that are fundamentally extractive and hierarchical. These systems do not serve a free nation. They were designed to rule over a population, not to serve it. Replacing them will take time, but the transition must begin with education reform. Schools and universities should ground students in the intellectual, artistic, and political contributions of Muslim India, not just in colonial history or rote memorization. Curricula must be reoriented to create citizens, not just subjects.

Second, the military must be restructured. Pakistan cannot continue to pour vast resources into a peacetime military that is socially and economically isolated from the population. A smaller, professional standing force should be retained for defense and strategic purposes. But the larger goal should be a flexible, citizen-based defense model. Civilian men and women should be trained, respected, and ready to serve if needed, just as they were in early Islamic societies. This would free up national resources and reintegrate the military with the population it is meant to protect.

Third, Pakistan must decentralize power and embrace local governance. Historically, Muslim empires in India maintained stability not through overcentralization but by giving autonomy to provinces, cities, and communities. Reviving this principle would allow Pakistan to bring governance closer to the people, make development more responsive, and reduce the alienation felt in Balochistan, Sindh, southern Punjab, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Regional pride can exist without threatening national unity, if that unity is based on shared purpose rather than forced conformity.

Fourth, economic reform must prioritize dignity and productivity over dependency and speculation. Pakistan must reinvest in agriculture, industry, and innovation, sectors where it once led and still holds potential. Incentivizing small and medium enterprises, rebuilding domestic manufacturing, and fostering research and development in technologies rooted in local needs (such as water management, textiles, and energy) can drive a new economic engine. The model should not be based on aid or extractive investment, but on internal strength and civilizational purpose.

Learning from Civilizational Revivals: The Example of China

The United Kingdom, Germany, Russia, France, and Japan put Qing China through “the century of humiliation”.

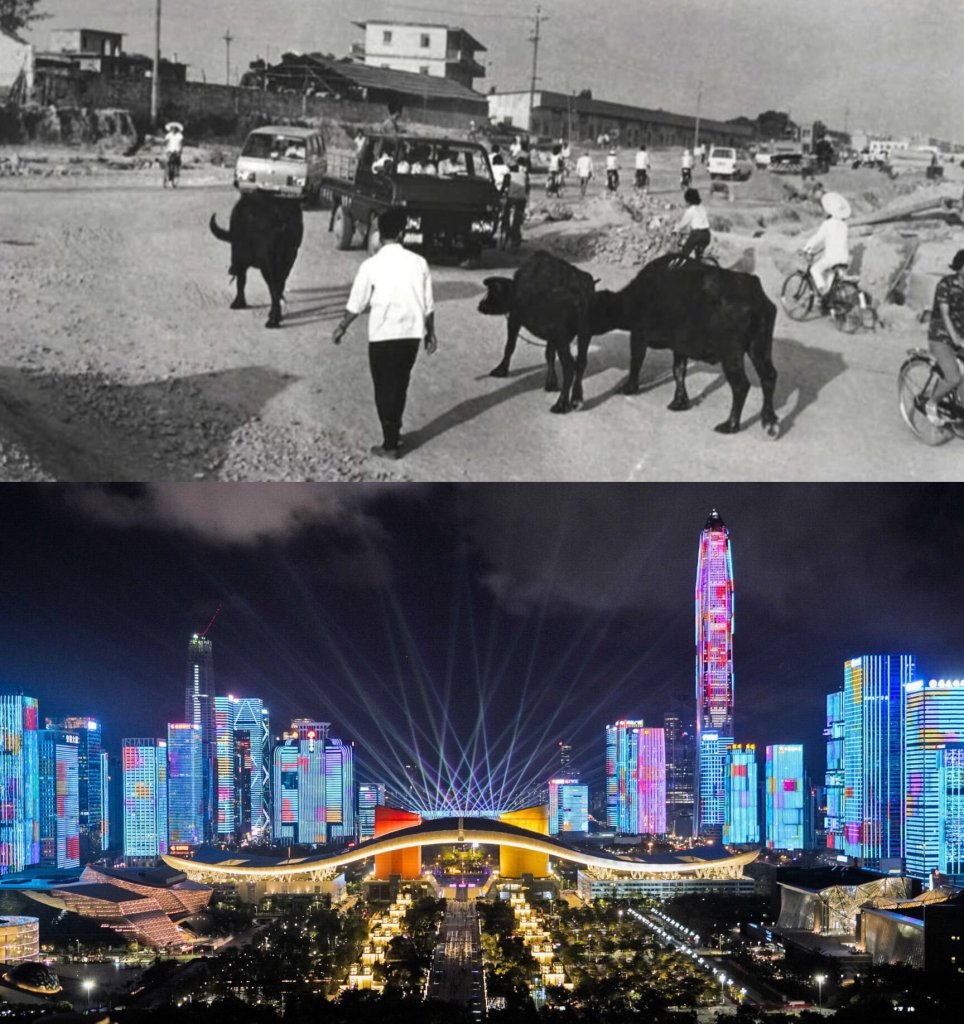

This kind of revival is not a fantasy. It has happened before, and it can happen again. One of the clearest modern examples is China. Just sixty years ago, China was a broken country, divided by civil war, plagued by poverty, and humiliated by colonial exploitation and foreign domination. By every measure, it was considered a backwater. Yet within a single generation, China initiated a sweeping transformation. It is now the world’s second-largest economy and has pulled over 800 million people out of poverty, creating the largest middle class in human history.

Two photos taken in Shenzhen, one from 1980 and the other from 2020.

What made this turnaround possible was not just economic policy or foreign investment. It was a civilizational memory, a deep and conscious return to China’s historical identity as a powerful, unified, and self-reliant civilization. Chinese leaders drew upon thousands of years of political philosophy, governance models, infrastructure-building practices, and cultural confidence. Rather than constantly looking outward for models to copy, China looked inward to find the roots of its national strength. Today, it is not just a country with money or military power, it is a civilization-state with coherence, direction, and purpose. Its modern policies are built atop a foundation laid by Confucian values, imperial administration, and dynastic resilience.

China’s rise was not inevitable. It was chosen by their people. Pakistan, too, must choose.

Pakistan, like China, possesses the raw material of a great civilization. This is not merely metaphorical, it is historical fact. The land Pakistan occupies today was once home to the Indus Valley Civilization, one of the earliest and most advanced urban societies in the ancient world. Mohenjo-daro and Harappa were thriving cities with planned infrastructure, trade networks, written language, and public sanitation at a time when much of the world lived in tribal settlements. The DNA of statecraft and innovation has been in this soil for millennia.

The Indus Valley civilization, in the ancient era, had advanced sewage removal, draining systems, and urban planning.

Centuries later, this same region became a vital part of the Muslim world’s expansion into South Asia. From the early Ghaznavid campaigns to the consolidation of the Delhi Sultanate and eventually the Mughal Empire, the territories now within Pakistan were home to dynasties that rivaled the Ottomans and Safavids in both military and cultural power. These empires built monumental cities, funded global trade, produced scholars and poets, and created administrative systems that governed millions with relative sophistication.

The legacy of Muslim India is not confined to a few monuments or stories, it is a blueprint. It shows what is possible when identity, governance, and vision align. That legacy belongs to Pakistan just as surely as the Great Wall belongs to China. But unlike China, Pakistan has not yet reclaimed its historical self. Instead of drawing strength from its roots, it has buried them under layers of colonial institutions, foreign dependency, and cultural insecurity.

Civilizational revival does not require perfection. It requires memory, clarity, and will. Pakistan’s past proves it can be a place of wealth, learning, justice, and beauty. The same soil, the same rivers, and the same people exist today. What is missing is leadership that sees the nation not as a geopolitical afterthought, but as the modern inheritor of one of history’s most enduring legacies.

The time to act is now. The world is shifting. Old powers are fading. New alliances are forming. And history favors those who know who they are