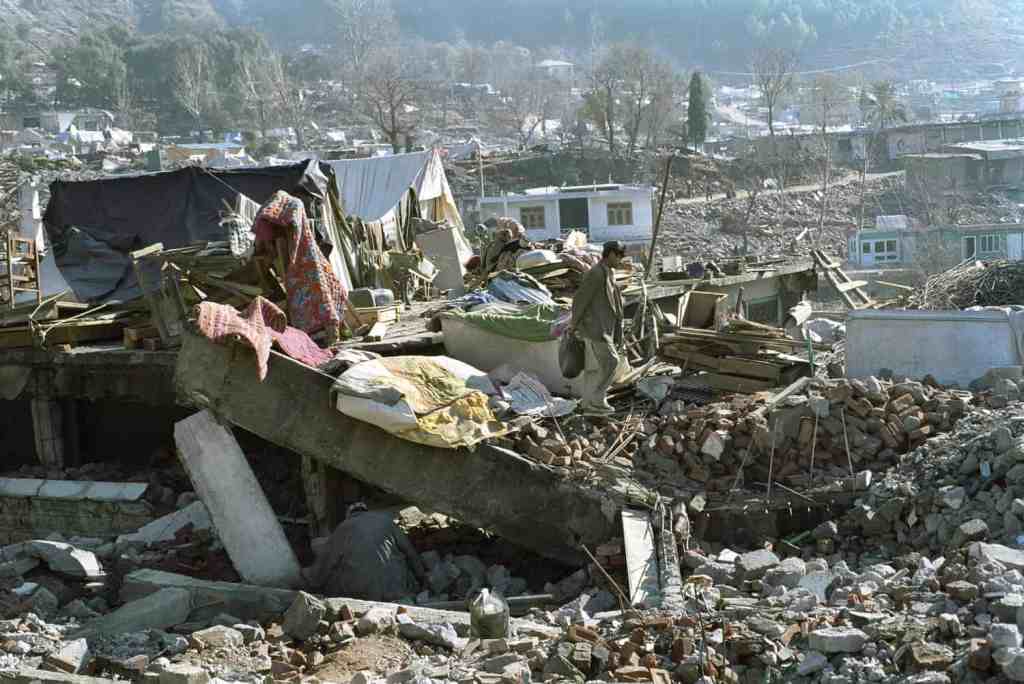

The recent 2025 India-Pakistan conflict, which erupted earlier this month, has showcased the intensity of the long-standing rivalry between the two nuclear-armed neighbors. While the conflict has primarily unfolded on land and in the air, there is a critical dimension that has remained largely untouched, India’s naval power and the significant threat it poses to Pakistan. As far as what is known, the Indian navy was not directly involved in the recent hostilities, India’s formidable naval capabilities could severely threaten Pakistan’s ports, maritime trade routes, and coastal infrastructure. Given Pakistan’s comparatively limited and outdated naval assets, addressing this imbalance is essential to maintaining national security.

Pakistan has emerged with several key insights into its military preparedness. Despite demonstrating resilience and tactical efficiency in air-to-air engagements, particularly with the successful deployment of advanced anti-air missile systems, the conflict has revealed a strategic vulnerability that cannot be ignored, the threat from the sea. As Sun Tzu wisely stated in The Art of War, “If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.” Pakistan must now apply this principle to its naval strategy, recognizing that while it performed well in the skies, its maritime security remains dangerously inadequate. Given the strategic importance of coastal infrastructure, maritime trade routes, and economic hubs like Karachi and Gwadar, the next inevitable confrontation with India could see a greater emphasis on naval power. To ensure national security, Pakistan must proactively address the gaps in its naval capabilities, not just as a reactive measure but as a fundamental component of its long-term defense strategy.

Indian Naval Strengths: A Strategic Threat

India’s naval doctrine emphasizes power projection and control over the Indian Ocean, reflecting its aspirations as a regional maritime power. The Indian Navy operates approximately 150 vessels, making it one of the largest navies in the region. Its primary components include aircraft carriers, destroyers, frigates, submarines, and various support vessels, all configured for extended blue-water operations.

India’s two active aircraft carriers, INS Vikramaditya and INS Vikrant, serve as strategic assets that enable air superiority at sea

India’s two active aircraft carriers, INS Vikramaditya and INS Vikrant, serve as strategic assets that enable air superiority at sea. These carriers, equipped with MiG-29K fighter jets and helicopters, allow for extended air operations, effectively projecting Indian air power into maritime zones. The ability to launch fixed-wing aircraft from the sea gives India the capability to bypass land-based air defenses, posing a strategic challenge to Pakistan’s coastal security.

Additionally, India’s fleet of 10 destroyers, including Kolkata-class and Visakhapatnam-class, are designed for multi-role combat, equipped with advanced sensors, anti-aircraft systems, and surface-to-surface missiles. These destroyers each feature approximately 32 VLS cells for Barak 8 SAMs and 16 cells for BrahMos missiles. Combined, these ships offer around 480 VLS cells, enabling robust air defense and significant offensive potential against both maritime and land-based targets.

The INS Surat, INS Nilgiri and INS Vaghsheer at the Naval Dockyard in Mumbai, Maharashtra on January 15, 2025

India’s 13 frigates, including Shivalik-class and Talwar-class, further strengthen its maritime strike and anti-submarine warfare capabilities. These ships provide versatile combat options, including ASW operations and integrated air defense. Moreover, the inclusion of nuclear-powered submarines, like the Arihant-class SSBNs and Chakra-class SSNs, significantly bolsters India’s second-strike capability, ensuring survivability in a nuclear conflict scenario.

Strategic Disparities: The Naval Imbalance

In the aftermath of the 2025 conflict between India and Pakistan, it has become increasingly clear that while Pakistan demonstrated competence in aerial engagements, its naval capabilities remain significantly inferior to India’s. As geopolitical tensions continue to simmer, it is imperative for Pakistan to address this strategic disparity. The most pressing concern is the vertical launch system (VLS) capacity gap, but this is just one aspect of a much broader issue. Understanding these disparities in detail and exploring strategic alternatives is crucial for maintaining a credible maritime deterrent.

VLS (Vertical Launch System) cells are central to modern naval combat, allowing warships to deploy a variety of missiles for anti-aircraft, anti-ship, and land-attack roles.

One of the primary areas of concern is the significant gap in Vertical Launch System (VLS) capacity. VLS are central to modern naval combat, allowing warships to deploy a variety of missiles for anti-aircraft, anti-ship, and land-attack roles. India’s VLS capacity far outstrips that of Pakistan, primarily due to its advanced destroyer and frigate fleet. The Kolkata-class and Visakhapatnam-class destroyers alone field approximately 480 VLS cells, capable of launching both the Barak 8 surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) and the BrahMos supersonic cruise missiles. These VLS systems grant India the ability to conduct massive missile saturation attacks, overwhelming smaller and less capable naval formations.

In stark contrast, Pakistan’s fleet, including its modern Type 054A/P frigates and Babur-class corvettes, fields a total of around 192 VLS cells. While the HQ-16 and LY-80N SAMs provide a medium-range air defense capability, their range (40 km) and speed are significantly inferior to the Barak 8 (100 km range) and the BrahMos (290 km range). This disparity limits Pakistan’s ability to establish air denial zones or engage Indian ships at a comparable distance. As a result, during a potential conflict, Indian naval forces could execute high-volume missile attacks from a safe distance, effectively neutralizing Pakistan’s surface combatants before they can respond.

Pakistan’s Chinese-built Type 54 A/P frigate is it’s most capable warship, equipped with a 32-cell VLS, which carries LY-80N surface-to-air missiles.

Another fundamental weakness in Pakistan’s naval posture is the lack of strategic depth and blue-water capability. India’s navy, with its aircraft carriers and nuclear-powered submarines, can operate far from its home shores, projecting power into the Arabian Sea and beyond. This capability allows India to control critical maritime chokepoints, such as the Strait of Hormuz and the Bab-el-Mandeb, which are vital for Pakistan’s energy imports and economic stability. In contrast, Pakistan’s naval forces are predominantly coastal and lack the endurance to sustain long-range missions. The Agosta-class submarines and Hangor-class additions are primarily designed for defensive operations in littoral waters, rather than extended deterrence. This difference in operational scope means that, in a worst-case scenario, Indian carrier strike groups could establish a blockade or conduct long-range strikes on key Pakistani ports such as Karachi and Gwadar, crippling Pakistan’s maritime trade and strategic logistics.

The disparity in anti-ship missile capabilities further exacerbates Pakistan’s vulnerabilities. The BrahMos missile, with its supersonic speed (Mach 3) and high precision, poses a severe threat to Pakistani naval assets. In contrast, the C-802A (180 km) and CM-400AKG (240 km) missiles lack both the range and the kinetic impact to neutralize heavily armed Indian surface combatants. Furthermore, the BrahMos’ ability to fly low and perform evasive maneuvers makes it a formidable challenge for Pakistan’s existing air defense systems. This technological gap underscores the need for Pakistan to modernize its anti-ship missile arsenal, potentially through collaboration with China to acquire longer-range and faster missile systems, such as the YJ-12 or YJ-18.

The YJ-18, a long range anti-ship cruise missile, or a similar variant would be a necessary addition to Pakistan’s arsenal to defend maritime security.

Compounding these challenges is India’s capacity for maritime air power. The Indian Navy’s aircraft carriers, INS Vikramaditya and INS Vikrant, serve as strategic assets that enable air superiority at sea. Equipped with MiG-29K aircraft, these carriers facilitate long-range strike missions and air dominance over contested waters. The ability to operate fixed-wing aircraft from the sea allows India to bypass land-based air defenses, posing a significant challenge to Pakistan’s coastal security. Without similar capabilities, Pakistan remains reliant on land-based aircraft to counter naval threats, significantly limiting its operational flexibility.

Strategic Impact of a Strong Pakistani Navy: Forcing India to Disperse Its Defenses

A robust and versatile Pakistani navy would fundamentally reshape India’s strategic defense posture, compelling it to disperse its military assets across a vast geographical area rather than concentrating them along the border. Currently, India’s strategic advantage lies in its ability to amass forces along the Line of Control (LoC) and the international border with Pakistan, maintaining pressure through superior ground force concentration. However, if Pakistan were to establish a credible naval threat with VLS-equipped destroyers and long-range strike capabilities, India would face a significant strategic dilemma.

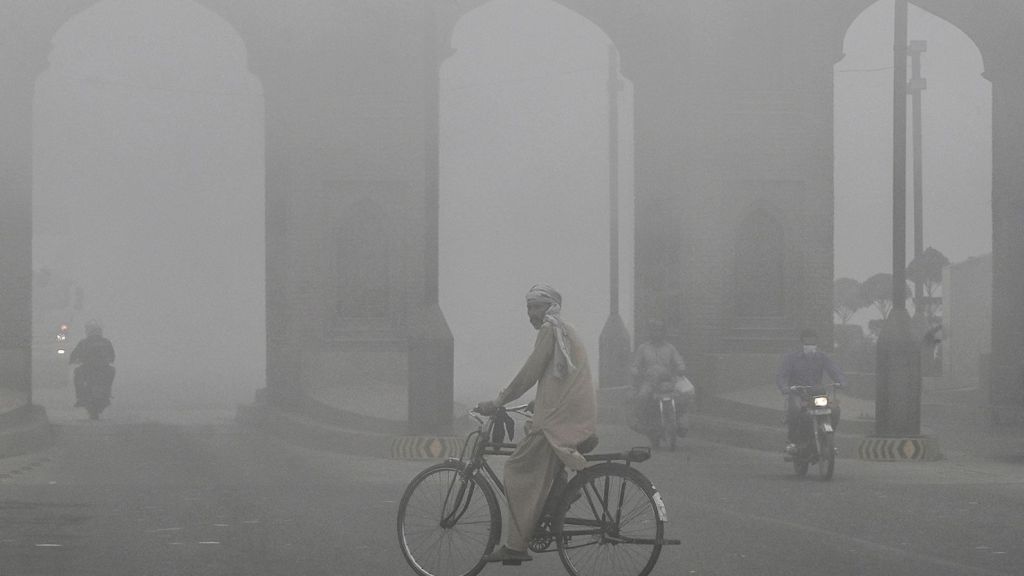

With a potent Pakistani naval presence potentially operating throughout the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean, India would be forced to reassess its defense distribution. Instead of focusing its anti-aircraft and anti-missile systems solely on the western border, India would need to secure its entire coastline, spanning over 7,500 kilometers, against potential maritime incursions and missile strikes from unexpected angles. This vast coastline includes critical economic hubs, naval bases, and densely populated coastal cities that would suddenly become vulnerable to naval-based land-attack missiles and anti-ship strikes.

A well-equipped Pakistani navy would force India to alter it’s defense posture. India’s vast coastline includes critical economic hubs, naval bases, and other military infrastructure that would suddenly become vulnerable to naval-based land-attack missiles and anti-ship strikes.

The deployment of VLS-equipped destroyers and long-range land-attack missiles would give Pakistan the ability to strike deep into Indian territory from the sea, including vital coastal infrastructure and military installations. This capability would force India to scatter its air defense systems and anti-missile assets across the entire length of its coastline rather than focusing them on the border regions. Consequently, India’s S-400 and Barak 8 SAM systems, which are typically stationed to protect against aerial threats from the west, would need to be repositioned to cover coastal vulnerabilities.

This redistribution of defensive assets would dilute India’s ability to maintain a concentrated defensive line along the border, thereby reducing its capacity to sustain land-based offensives. Furthermore, Indian naval forces, which are currently focused on projecting power into the Indian Ocean, would need to adopt a more defensive posture, patrolling vast coastal areas to mitigate the threat of sudden strikes from Pakistani ships or submarines.

By compelling India to extend its defensive coverage from the land border to the entire coastline, Pakistan would significantly reduce the pressure on its ground forces. This strategic naval posture would create a more balanced distribution of Indian forces, enabling Pakistan to exploit any resulting gaps in India’s border defenses. In essence, a powerful and mobile Pakistani navy would not only enhance maritime security but also indirectly bolster Pakistan’s land-based defense by forcing India into a more scattered and less cohesive military deployment.

VLS Destroyers: Expanding Strike Capabilities

One of the most significant strategic advancements that Pakistan must focus on is the acquisition and development of VLS-equipped destroyers. Vertical Launch System (VLS) destroyers are critical for modern naval combat as they allow a single ship to deploy a wide array of munitions, including surface-to-air, anti-ship, and land-attack missiles. The strategic advantage of VLS destroyers lies not only in their firepower but also in their ability to project power far beyond their immediate vicinity. For Pakistan, acquiring VLS-equipped ships would significantly enhance its ability to threaten Indian assets along the entirety of India’s coastline.

Currently, India’s Kolkata-class and Visakhapatnam-class destroyers are equipped with around 480 VLS cells, allowing them to launch both the BrahMos supersonic cruise missiles and Barak 8 surface-to-air missiles. This configuration provides the Indian Navy with a formidable combination of anti-ship strike capability and aerial defense. By contrast, Pakistan’s naval forces have around 192 VLS cells distributed among their Type 054A/P frigates and Babur-class corvettes, which limits their ability to engage both aerial and maritime threats simultaneously.

Investing in multi-role destroyers with significant VLS capacity would allow Pakistan to expand its strike capability to include not only defensive measures but also offensive operations deep within Indian territory. With destroyers positioned in the Arabian Sea, Pakistan could theoretically target vital Indian infrastructure, including military bases and logistical hubs, forcing India to disperse its defensive assets across the entire coastline. This dispersal would prevent India from concentrating its forces at key maritime chokepoints, thereby reducing its ability to respond effectively to multi-vector threats.

Importance of Land-Attack VLS Missiles

One crucial aspect that Pakistan must consider when developing its VLS-equipped fleet is the inclusion of land-attack missile capabilities. Land-attack missiles launched from destroyers offer strategic depth by enabling long-range strikes on key enemy infrastructure, logistics hubs, and command centers. This capability forces the adversary to consider potential strikes not just from land-based launchers but also from naval platforms, which are mobile and can operate in international waters. For Pakistan, deploying land-attack VLS missiles would mean the ability to target strategic Indian military installations from unexpected angles, complicating India’s defensive planning.

The US Navy’s tomahawk land-attack missiles allow global force projection.

By incorporating VLS systems capable of launching land-attack missiles like the CJ-10 or similar systems, Pakistan can significantly enhance its deterrence posture. These missiles, when integrated into naval destroyers, offer a second-strike capability that can be deployed rapidly from the sea, minimizing the threat of pre-emptive destruction. The ability to launch such strikes from various points along the coast or even from the Arabian Sea would stretch Indian air and missile defenses, forcing a wider and less efficient distribution of their anti-missile assets.

Lessons from Ukraine’s Naval Strategy

Ukraine’s conflict with Russia in the Black Sea has shown that even a relatively weaker power can effectively challenge a larger adversary using asymmetric tactics. Despite having no significant navy of its own, Ukraine managed to neutralize Russia’s Black Sea Fleet flagship, the Moskva, using land-based Neptune anti-ship missiles. Since the conflict began, Russia has lost at least 18 naval vessels, including patrol boats and amphibious landing ships, primarily due to Ukraine’s use of precision missile strikes and drones. The sinking of the Moskva, in particular, demonstrated how even a highly capable warship could be defeated by focused, well-coordinated missile attacks from land-based systems.

Ukraine, a country without a navy, sunk the Russian Navy’s Black Sea Flagship, the Moskva.

For Pakistan, this lesson is invaluable. Rather than attempting to match India’s fleet size, Pakistan can develop a distributed network of coastal missile batteries equipped with advanced Chinese anti-ship missiles like the YJ-12 and YJ-18. Additionally, investing in autonomous naval drones for reconnaissance and targeted strikes would significantly enhance Pakistan’s maritime denial capabilities. This approach would force India to reconsider any naval advance, as its ships could be at risk even without encountering Pakistan’s surface fleet directly.

Sino-Pakistani Naval Collaboration

China’s experience in shipbuilding and its strategic partnership with Pakistan offer a unique opportunity to address Pakistan’s naval gaps. China has become one of the world’s largest shipbuilders, producing advanced destroyers like the Type 055, which features significant VLS capacity and advanced radar systems. By collaborating with China, Pakistan could not only acquire such ships but also develop the technical expertise required to build and maintain them domestically. Establishing a robust shipbuilding industry with Chinese assistance would enable Pakistan to gradually reduce its dependence on foreign suppliers and ensure that future expansions of its fleet are both cost-effective and strategically aligned with national defense goals.

China’s experience in shipbuilding and its strategic partnership with Pakistan offer a unique opportunity to address Pakistan’s naval gaps. China has become one of the world’s largest shipbuilders.

A critical element of this collaboration would be developing Pakistan’s shipyards to build modern destroyers and frigates domestically. Learning from China’s efficient shipyard practices, Pakistan could train dockworkers and engineers to handle advanced naval projects. This capacity-building would not only boost local industries but also create a sustainable model for maintaining and upgrading the fleet. Furthermore, Pakistan’s role in co-producing naval assets could indirectly support China’s regional ambitions by providing a secondary production site for ships and support vessels, benefiting both nations in terms of strategic flexibility.

Asymmetric Naval Warfare: An Effective Counter

Given India’s numerical and technological superiority at sea, Pakistan must focus on asymmetric naval strategies to level the playing field. Instead of attempting to match India ship-for-ship, Pakistan should develop tactics that exploit the vulnerabilities of larger, more complex naval formations. One of the most promising approaches is the deployment of naval denial drones. These drones, equipped with anti-ship missiles or torpedoes, can harass Indian patrols and escort vessels from a safe distance. By using autonomous or remotely piloted systems, Pakistan could maintain a persistent threat without exposing valuable manned assets to counterattack. Such drones would not only enhance situational awareness but also create operational uncertainty for Indian naval commanders.

Another critical tactic is the use of swarm attacks. Coordinating multiple fast attack craft to strike larger Indian ships simultaneously can overwhelm their defensive systems. Instead of directly engaging heavily armed destroyers or frigates, Pakistan can focus on targeting logistics and support vessels, effectively disrupting Indian fleet cohesion and resupply operations. These swarm tactics would be particularly effective in confined or contested waters where maneuverability is limited.

Ukrainian maritime drones are an asymmetric method of denying the Russian Navy supremacy over the Black Sea. Pakistan should aim to develop similar asymmetrical methods.

To maintain strategic flexibility, Pakistan should also develop mobile missile units equipped with long-range anti-ship missiles. These coastal defense systems must be easily relocatable to reduce the risk of preemptive strikes. By positioning these units near key maritime chokepoints, Pakistan can deter Indian naval advances while maintaining the ability to strike from unexpected locations. The mobility of these units would also complicate India’s targeting process, forcing it to allocate more resources for surveillance and intelligence gathering.

Furthermore, Pakistan should incorporate underwater mines and sabotage operations into its naval doctrine. Placing mines near strategic naval bases or maritime chokepoints would limit India’s ability to maneuver freely, particularly in shallow or narrow passages. Additionally, using submarines to deploy mines covertly would increase their effectiveness, as Indian naval planners would have difficulty detecting and neutralizing these hazards in time. In conjunction with mines, sabotage operations against port infrastructure could further degrade India’s ability to sustain prolonged naval deployments.

To make these asymmetric strategies sustainable, Pakistan needs to implement several strategic recommendations. First, investing in multi-role destroyers with high VLS capacity will allow Pakistan to project power into Indian waters and beyond, maintaining a credible deterrent. Second, enhancing anti-ship and land-attack missile capabilities by integrating Chinese YJ-12, YJ-18, and CJ-10 missiles into both naval and land-based platforms would give Pakistan the ability to strike from multiple vectors. Developing maritime drone programs is also crucial, as autonomous drone fleets could be used for surveillance, reconnaissance, and direct anti-ship operations, significantly increasing situational awareness and strike capability without risking manned assets.

Moreover, strengthening domestic shipbuilding through Sino-Pakistani collaboration will be vital for sustaining a modern and flexible navy. Establishing shipyards capable of producing destroyers and frigates would not only reduce dependency on foreign acquisitions but also foster technological innovation. This long-term investment would support rapid fleet expansion and maintenance, essential for maintaining a strategic naval presence.

Lastly, Pakistan must adopt asymmetric tactics as a core component of its naval doctrine. Training naval units in swarm attacks, missile ambushes, and drone warfare will enable the navy to operate efficiently even with limited resources. By leveraging these unconventional strategies, Pakistan can effectively deny India’s freedom of movement at sea, forcing it to remain cautious and reducing its ability to project naval power unopposed.