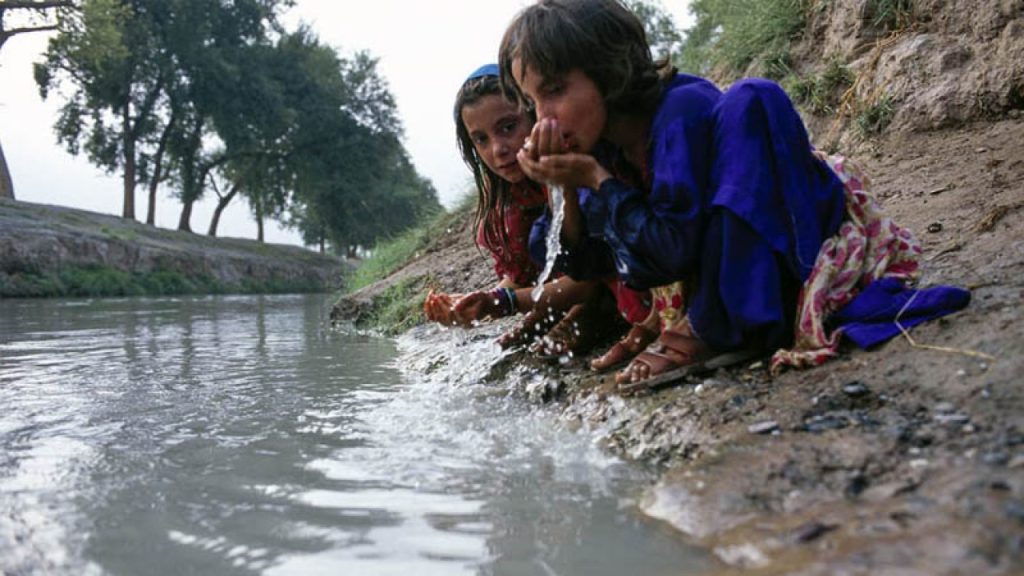

Access to clean, piped water in Pakistan remains one of the most overlooked crises in national development. According to the Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement (PSLM) Survey, only 36% of households in the country have access to piped drinking water, with rural areas facing far lower rates, some provinces report figures below 20%. Even in major cities like Karachi and Rawalpindi, piped supply is often irregular, unfiltered, and supplemented by private tankers or underground boreholes, many of which deliver contaminated water. The situation is so dire that the UNICEF/WHO Joint Monitoring Program ranks Pakistan among countries with the highest proportion of population relying on unimproved or unsafe sources of drinking water in South Asia.

This article explores why clean, piped water is not a secondary public service but a foundational pillar for modern life. Without it, Pakistan’s public health system remains overburdened by preventable waterborne diseases, its women and children are trapped in daily cycles of water collection, and its cities are stalled from scaling vertical housing and industrial growth. Water insecurity fuels not only poverty but also political instability, environmental degradation, and widening inequality.

A modern piped water infrastructure, combined with localized filtration plants and national delivery standards, must be treated with the same urgency and investment as power grids, highways, and national defense. This article presents a comprehensive look at the depth of Pakistan’s water access problem, its human and economic costs, and lays out a forward-facing infrastructure policy blueprint rooted in local capabilities, engineering talent, and long-term strategic planning.

Pakistan’s Alarming Water Access Statistics

According to the Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement (PSLM) 2019–20 survey, only 36.4% of households nationwide have direct access to piped water.

Pakistan faces a severe and systemic failure in providing clean, piped water to its population. According to the Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement (PSLM) 2019–20 survey, only 36.4% of households nationwide have access to piped water. This access is heavily skewed by region: while 61.8% of urban households are connected to some form of piped system, only 18.7% of rural households receive the same. The disparity is even more stark in provinces like Balochistan, where rural piped access is as low as 6%, and Sindh, where rural coverage remains under 10% despite the province hosting major industrial zones. Even in urban settings, piped water access does not necessarily imply connectivity to a functional, city-wide water main. In many cases, what is reported as “piped water” refers to informal setups, such as overhead neighborhood tanks or boreholes, rather than centralized, filtered, or reliably pressurized systems. The Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR) has repeatedly noted that most so-called piped water is simply untreated groundwater pumped into localized distribution lines.

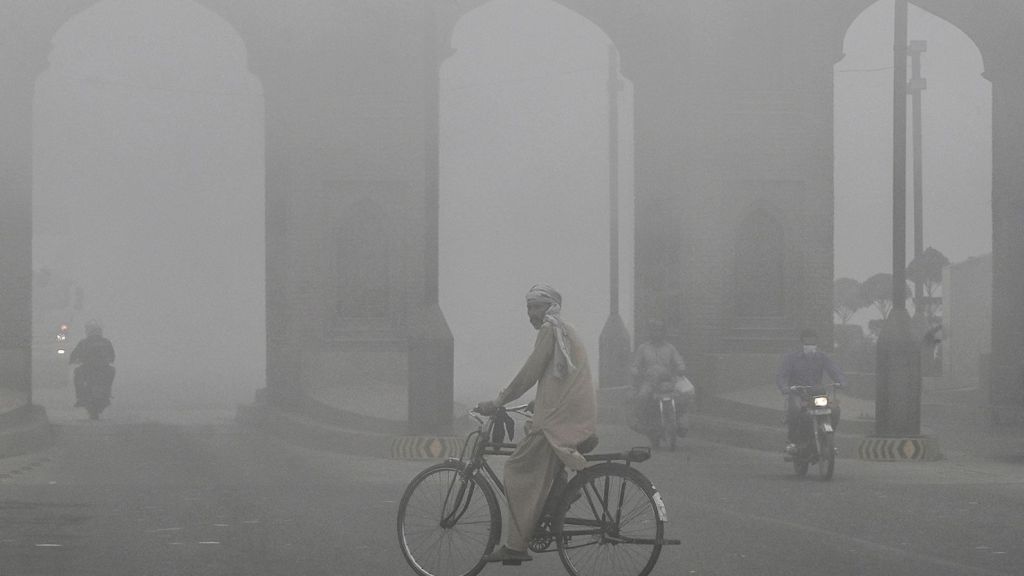

Major cities, which should represent the best-case scenarios, also expose the depth of the crisis. In Karachi, only 55% of total demand is met by the official municipal network operated by the Karachi Water and Sewerage Board (KW&SB), with the remainder coming from private tankers, illegal hydrants, and unregulated groundwater extraction. A 2021 study by the Karachi Water Partnership found that fewer than half of connected households receive water on a daily basis, with many neighborhoods reporting availability just once or twice per week. In Quetta, piped infrastructure covers less than 30% of the population, leaving residents to purchase water at exorbitant rates as groundwater reserves run dry. Lahore offers broader coverage through WASA, yet over 90% of the city’s supply is sourced from unfiltered groundwater, with little to no chlorination. An estimated 30–40% of water is lost due to leakage in the aging pipeline system.

By global and regional standards, Pakistan is drastically underperforming. India has expanded rural piped water coverage from 17% in 2019 to over 67% in 2023 under the Jal Jeevan Mission. Bangladesh has piped water access for 74% of its urban population, while Vietnam has achieved over 85% national coverage through coordinated, state-led infrastructure programs. Pakistan, by contrast, has failed to meet the UN Sustainable Development Goal 6.1, which calls for universal access to safe and affordable drinking water by 2030. The country’s lack of integrated, municipally managed water systems, especially those tied to filtration and pressure regulation, means that even where pipes exist, they often deliver unsafe, irregular, or no water at all.

India has expanded rural piped water coverage from 17% in 2019 to over 67% in 2023 under the Jal Jeevan Mission.

Ultimately, Pakistan’s water infrastructure is not just insufficient, it is fragmented, unsafe, and unjust. Without a centralized, city-wide piped water and treatment system, the idea of “access” remains hollow. The crisis is not one of scarcity alone, but of broken governance, chronic underinvestment, and systemic neglect.

Health Impact of Unsafe and Inadequate Water

The public health consequences of Pakistan’s broken water infrastructure are profound and far-reaching, touching nearly every aspect of life. Contaminated and insufficient water supply is directly linked to some of the country’s most persistent disease burdens, including cholera, typhoid, acute diarrhea, dysentery, hepatitis A and E, and parasitic infections. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 53,000 children under the age of five die annually in Pakistan due to diarrheal diseases, most of which are entirely preventable through access to clean drinking water and improved sanitation. These deaths represent only the visible peak of a much larger crisis—millions of cases of waterborne illnesses go unreported or untreated each year, especially in rural and peri-urban areas.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 53,000 children under the age of five die annually in Pakistan due to diarrheal diseases, most of which are entirely preventable.

The economic burden this places on Pakistan’s healthcare infrastructure is staggering. A 2021 study published in The Lancet Regional Health estimated that Pakistan loses up to 4% of its GDP annually due to poor water and sanitation conditions, a figure that includes not only direct healthcare costs but also lost productivity, school absenteeism, and premature mortality. Public hospitals in high-density urban centers like Karachi and Lahore frequently report seasonal spikes in gastrointestinal infections, overwhelming limited resources. In rural areas, where clinics are scarce or underfunded, many communities rely on self-medication or informal care, often leading to chronic health issues or preventable deaths.

Women and children bear the brunt of this crisis. In areas without reliable piped water, they are often tasked with walking long distances, sometimes over 3–5 kilometers daily, to fetch water from wells, boreholes, or shared tanker supplies. This has a direct impact on female education and employment; a UNICEF report estimates that in water-insecure districts, girls are 20% more likely to drop out of school compared to those with basic infrastructure. The time and energy spent on water collection reduce opportunities for productivity further exposing women and children to risks of harassment and assault during collection routines, especially in remote or conflict-prone regions.

Case studies from Pakistan’s most water-stressed regions reveal the scale of human suffering. In Tharparkar, Sindh, which has long struggled with drought and food insecurity, contaminated groundwater, often the only available source, is known to contain dangerously high levels of fluoride, nitrates, and fecal coliform bacteria. A 2018 health audit by the Sindh Health Department linked poor water quality to widespread cases of stunting and wasting among children, compounded by chronic diarrhea and undernutrition. In Baluchistan’s Awaran and Washuk districts, villagers rely on shallow, seasonal ponds or manually dug wells, many of which run dry before the end of the dry season. These stagnant sources are highly vulnerable to animal waste contamination and mosquito breeding, leading to seasonal outbreaks of diarrhea, malaria, and skin infections.

The structural deficiencies in Pakistan’s water delivery system amplify this health burden. In most cities, there is no guarantee that piped water is treated. Filtration, if it exists at all, is often outdated, poorly maintained, or bypassed altogether. The lack of residual chlorination in most municipal systems increases the risk of bacterial growth in distribution lines. Moreover, intermittent water supply creates negative pressure in pipes, which draws in contaminants from surrounding soil or sewage, a problem well-documented in unplanned settlements like Orangi Town in Karachi and Bhara Kahu in Islamabad.

In short, unsafe and inadequate water is not simply a hygiene issue, it is a national health emergency. It silently undermines the productivity of the labor force, imposes long-term cognitive and physical developmental damage on children, and traps households in cycles of illness and poverty. Without substantial reform and investment in safe, piped water infrastructure, Pakistan cannot expect to reduce its disease burden, improve life expectancy, or advance toward any serious development goals.

Water Access as a Foundation of Urban and Rural Growth

Water infrastructure is not just a health concern, it is the unseen engine behind national development. In Pakistan, the lack of a reliable, centralized, and piped water delivery system is quietly undermining the country’s ability to urbanize, industrialize, and modernize. Every pillar of economic activity, agriculture, housing, industry, and commerce, depends on consistent water access. Yet in the absence of a functioning public water network, entire sectors remain constrained, forcing reliance on informal, inefficient, and often exploitative alternatives.

Every pillar of economic activity, agriculture, housing, industry, and commerce, depends on consistent water access.

Industrial growth, particularly in designated special economic zones (SEZs) and export-oriented manufacturing clusters, requires not only power but a dependable supply of water. Textile mills, food processing plants, pharmaceutical facilities, and steelworks all require thousands of liters of clean water per day for cooling, cleaning, and production processes. In cities like Faisalabad and Korangi (Karachi), industrial units report paying significant premiums to secure water through private tankers or illegal hydrants, diverting capital from productivity into crisis mitigation. A 2020 Karachi Chamber of Commerce survey found that 60% of industrial respondents in Korangi and Landhi rely on non-municipal sources, with some paying up to PKR 1 million per month for tanker-supplied water. These costs not only reduce competitiveness but create artificial barriers to small and medium enterprise entry, entrenching monopolistic structures.

Many real estate projects are developed without guaranteed connections to piped water, relying instead on borewells, tankers, or community tanks.

In housing and real estate development, the absence of water pipelines halts or distorts growth. Many real estate projects in peri-urban zones, such as those ringing Islamabad, Lahore, and Gwadar, are developed without guaranteed connections to piped water, relying instead on borewells, tankers, or community tanks. This has led to unsafe and inequitable access, inflated service costs, and the proliferation of illegal or substandard housing developments. The unregulated sprawl of housing colonies often outpaces the ability of city governments to provide basic utilities, contributing to urban slums and failed municipal oversight. Even high-income housing schemes resort to importing water via truck, creating an absurd situation where multimillion-rupee properties remain functionally disconnected from public water networks.

Modern sanitation and vertical housing are also impossible to scale without piped water. High-density housing, apartment blocks, and commercial plazas require high-pressure water systems and integration with sewage treatment networks, none of which can be built or regulated effectively in the absence of city-wide water infrastructure. Without piped supply and pressure-regulated delivery, urban planning remains stuck in a low-rise, horizontal model, leading to urban sprawl, inefficient land use, and skyrocketing transport costs.

Tanker mafias, operating with impunity in cities like Karachi, Lahore, and Hyderabad, extract groundwater through illegal boreholes or seize control of public hydrants, reselling water to homes, businesses, and even hospitals at inflated prices.

Perhaps most corrosively, the vacuum left by the state has been filled by an informal, parallel economy. Tanker mafias, operating with impunity in cities like Karachi, Lahore, and Hyderabad, extract groundwater through illegal boreholes or seize control of public hydrants, reselling water to homes, businesses, and even hospitals at inflated prices. The Karachi Water and Sewerage Board estimates that over 30 million gallons per day are diverted or stolen by private actors, costing the city billions of rupees annually. Meanwhile, widespread drilling of private borewells, many unlicensed and unregulated, has led to rapid aquifer depletion, with cities like Quetta and Islamabad now facing long-term risks of groundwater exhaustion. In the absence of coordinated regulation, Pakistan’s water economy has become fragmented, corrupt, and ecologically unsustainable.

A centralized, publicly managed water delivery network would reverse this dynamic. It would lower transaction costs, improve urban planning, enable vertical housing, reduce public health risks, and shift water from being a black-market commodity to a guaranteed civic service. Most importantly, it would provide the basic infrastructure needed to support large-scale employment, housing, and commercial development, particularly in areas targeted for industrial growth and rural uplift. Without it, Pakistan will remain stuck in a high-cost, low-efficiency development trap where even basic progress is undermined by water scarcity and institutional neglect.

Water as a National Security Issue

In Pakistan, water is no longer simply a development concern, it has become a strategic vulnerability. As water scarcity intensifies, it is enabling criminal economies, and increasing Pakistan’s exposure to external coercion. The country’s lack of resilient, integrated water infrastructure is not just a policy failure; it is a threat to national sovereignty and internal stability.

At the micro level, water theft and tanker mafias have turned water access into a contested, often violent issue within cities. In Karachi, clashes between residents, tanker operators, and informal “hydrant syndicates” are common, with police and municipal officials sometimes complicit in the illicit trade. Control over illegal water sources, whether boreholes, hydrants, or diverted municipal supply, has become a source of income for organized criminal groups, further eroding the rule of law. In rural Baluchistan and southern Punjab, tribal conflicts have been exacerbated by the drying of shared water ponds and the uncontrolled digging of tube wells that rapidly deplete aquifers. The absence of a reliable, state-managed water delivery system creates a vacuum in which violence, extortion, and inequality thrive.

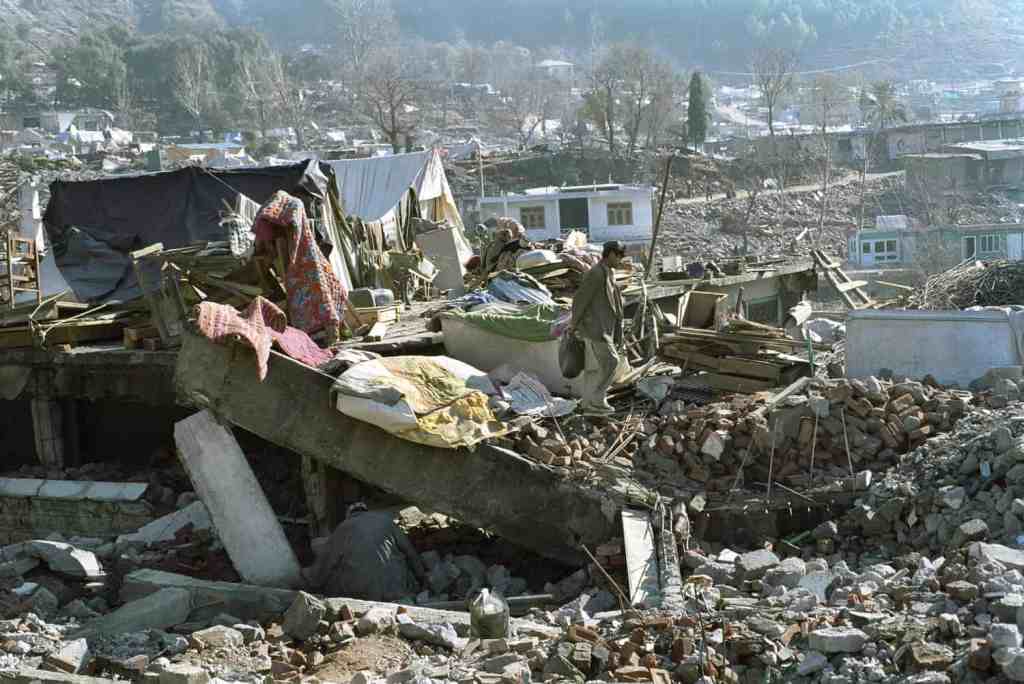

Climate change will exacerbate this crisis further. Pakistan is among the top 10 countries most vulnerable to climate-induced water stress, according to the Global Climate Risk Index. Melting glaciers in the north and erratic monsoon patterns in the south will intensify the country’s already volatile water cycles. Without large-scale piped distribution networks, urban reservoirs, and rural recharge systems, Pakistan has no tools to adapt. Instead, floods and droughts strike with increasing frequency, and communities must rebuild infrastructure from scratch after every event. Worse, without distributed and redundant water delivery systems, entire cities or provinces can be cut off from clean water during crises, natural or political.

This threat is no longer hypothetical. In May 2025, India suspended its participation in the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), an unprecedented move. While the suspension was framed as a response to geopolitical tensions, it exposed Pakistan’s fragile dependence on a single external water agreement for the survival of its agriculture and hydrology. Without the internal infrastructure to store, distribute, and manage its own water efficiently, Pakistan remains vulnerable to any upstream manipulation, whether from a hostile neighbor or a changing climate.

Singapore’s Public Utilities Board (PUB) has built a water management system so advanced that the country is nearly water self-sufficient despite having no natural water resources.

By contrast, countries like Singapore, China, and South Korea treat water infrastructure as an arm of statecraft. Singapore’s Public Utilities Board (PUB) has built a water management system so advanced that the country is nearly water self-sufficient despite having no natural water resources. Through a combination of piped water grids, rainwater harvesting, desalination, and reuse systems, Singapore has ensured that no external actor can weaponize water against it. China’s South-to-North Water Diversion Project, the largest of its kind in the world, is an example of water planning integrated into national development and regional equity strategies. These systems are not just technical marvels; they are political guarantees that water will not become a tool of blackmail or division.

For Pakistan, the lesson is clear: water infrastructure must be designed not just for utility, but for sovereignty and resilience. The country needs redundant, interlinked, and metered piped water systems across all provinces, capable of distributing both surface and treated groundwater in a crisis. Urban pipelines must be looped into regional reservoirs and groundwater recharge points. Industrial and agricultural zones must be connected to insulated municipal grids that reduce waste and dependency on tanker mafias. Ultimately, just as states invest in energy independence and food security, Pakistan must now treat water security as an extension of national defense, a buffer against foreign pressure, internal conflict, and ecological collapse.

What Needs to Be Done: A National Water Infrastructure Plan

Addressing Pakistan’s water crisis requires more than isolated projects, it demands a cohesive, state-led National Water Infrastructure Plan. This plan must aim to abolish the country’s dangerous reliance on unfiltered groundwater, illegal boreholes, and tanker mafias, while laying the foundation for city-scale piped water networks backed by modern treatment systems. The challenge is monumental, but so are the opportunities: Pakistan possesses the necessary labor force, raw materials, engineering talent, and strategic incentive to execute this transformation, provided it can mobilize them under a coherent national vision.

At the heart of this plan should be the mandatory development of municipal and district-level water masterplans, each tied to localized treatment plants and zoned pipeline networks. These plans must shift the country away from its current patchwork model of borewells and tankers toward a grid-based water delivery system, modeled on how cities manage electricity or gas. Each city’s masterplan must include surface reservoirs, distribution pumping stations, and redundant supply loops to ensure pressure stability and emergency resilience.

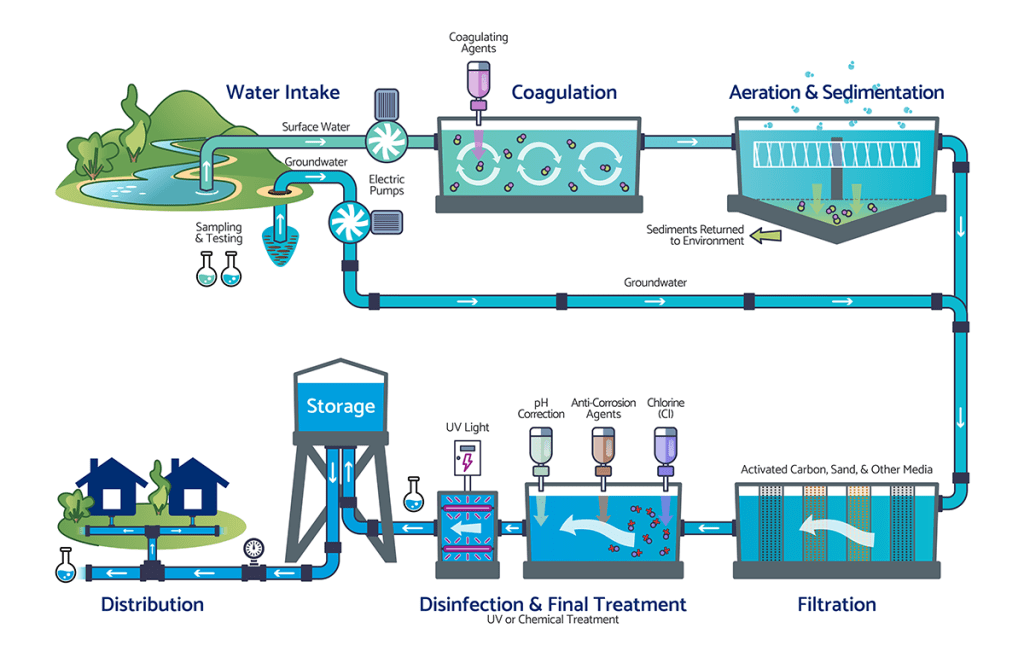

To bridge the gap between national ambition and local delivery, the federal government should invest in modular water treatment units, using membrane filtration, UV sterilization, and real-time quality sensors. These compact systems can be deployed rapidly at the union council or tehsil level, offering a decentralized solution while larger infrastructure is built. These facilities should be staffed and maintained by a new generation of locally trained civil and environmental engineers, supported by nationwide technical certification programs that can also create thousands of jobs—particularly for youth in underdeveloped areas.

To implement and coordinate this effort, Pakistan must either restructure the existing National Water Authority or establish a new, autonomous, technocratic agency. This agency would operate with provincial branches but be empowered to set national standards, issue planning directives, and regulate pricing and quality assurance. It would also coordinate interprovincial water data sharing, monitor aquifer levels and pipeline efficiency, and serve as the enforcement arm to eliminate illegal water extraction and tanker profiteering.

From manufacturing PVC and steel piping to building dams, filtration plants, and urban pumping stations, every component of this infrastructure should be produced domestically wherever possible.

On the financing side, Pakistan has several underutilized advantages. The country has a large, underemployed labor pool, particularly in the construction, engineering, and public works sectors. Drawing inspiration from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, which mobilized unemployed Americans during the Great Depression to build lasting public infrastructure, Pakistan should pursue a similar state-led employment-based infrastructure strategy. From manufacturing PVC and steel piping to building dams, filtration plants, and urban pumping stations, every component of this infrastructure should be produced domestically wherever possible. This not only keeps costs down but strengthens industrial self-reliance, feeding directly into broader goals of economic sovereignty and import substitution.

Pakistan must adopt a realist but self-reliant strategy, one that avoids further entrenching the country in debt or dependency. Rather than relying on loans or external bonds that feed the growing debt spiral, Pakistan should focus on two pragmatic avenues: leveraging existing development partnerships and revamping its domestic taxation system.

Pakistan already maintains technical and financial cooperation agreements with several nations and multilateral institutions, including China (under CPEC Phase II), Germany (via GIZ), Japan (JICA), Turkey, and the Islamic Development Bank. These partnerships can be restructured or expanded to include in-kind support for water infrastructure development, such as the transfer of filtration technologies, workforce training, and support in digital metering or leak detection systems. Instead of seeking cash-based lending, Pakistan should prioritize technical assistance, equipment procurement partnerships, and engineering exchange programs that help upgrade domestic capacity without triggering unsustainable repayments.

The most sustainable long-term source of financing, however, lies within Pakistan itself, specifically in modernizing the national tax regime. As of 2023, fewer than 3 million people in a population of over 240 million file income taxes, and indirect taxes on fuel, utilities, and imports disproportionately burden the poor. To fund large-scale public works such as a national water infrastructure plan, Pakistan must rebuild public trust in taxation. That means beginning with visible anti-corruption enforcement, reducing discretionary funds, and digitizing tax collection systems for transparency. The water sector, in particular, offers an opportunity to tie taxation to service delivery: if cities can show consistent, reliable piped water backed by metered billing, more citizens and businesses may be willing to pay utility-linked municipal taxes or service fees.

This is a moment to shift the narrative from dependency to sovereignty. Rather than waiting for bailout packages or conditional grants, Pakistan must build a developmental state model that relies on its own workforce, domestic manufacturing, and reformed institutions. Water infrastructure is one of the few sectors where value creation and fiscal recovery can occur simultaneously, provided it is planned and executed with integrity, transparency, and a long-term vision. By cutting waste, curbing leakages (both literal and fiscal), and holding officials accountable, Pakistan can finance its own transformation, without adding another dollar to its debt ledger.

Finally, this plan must be institutionally insulated from short-term political interference. Water infrastructure is generational in nature. A national compact on water, legislated through Parliament or enshrined in a federal-provincial development agreement, must protect this program from budgetary neglect or provincial resistance. Just as nations safeguard their defense and energy sectors, Pakistan must recognize that clean water is not a consumable commodity, but a strategic asset. The time for scattered boreholes and unregulated tanker monopolies is over. What Pakistan needs now is a coordinated, publicly led, and domestically produced water infrastructure system, capable of delivering not just hydration, but development, stability, and national dignity.

Basic Policy Recommendations

Fixing Pakistan’s water crisis does not require endless committees, pilot projects, or donor roadmaps, it requires action. Piped water access must be treated as a basic municipal responsibility, enforceable by law and backed by proper funding. All new housing schemes and industrial zones must be required to connect to centralized filtration and distribution networks from the outset. The government should commit to universal piped coverage in high-density districts within ten years, with clear targets and public tracking. Groundwater extraction in depleted areas must be banned, and basic pricing mechanisms introduced to prevent waste. Equally important is the need to build public understanding: schools and media must reinforce the message that clean water is a right and a shared duty. Bureaucratic paralysis has delayed this for decades. It’s time to stop studying the problem and start solving it.

Piped water is not a luxury, it is the foundation of public health, dignity, and national development. Pakistan has the people, materials, and technical expertise to build what is needed. What it lacks is a system that acts. Every delay widens inequality, fuels disease, and deepens dependence on informal, corrupt, and unsafe alternatives. The time for planning is over. The infrastructure must be built. No nation can progress while its citizens are denied safe water. A just, modern Pakistan begins at the tap.