Pakistan is one of the most seismically active countries in the world, yet it remains dangerously underprepared for a major earthquake. The country sits along a complex and active fault system where the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates meet, placing millions of lives and critical infrastructure at serious risk. While earthquakes are natural events, the scale of devastation they cause is shaped by human decisions. The 2005 Kashmir earthquake, which killed more than 80,000 people, exposed deep structural weaknesses in building safety, emergency preparedness, and disaster response. Nearly two decades later, many of those vulnerabilities persist.

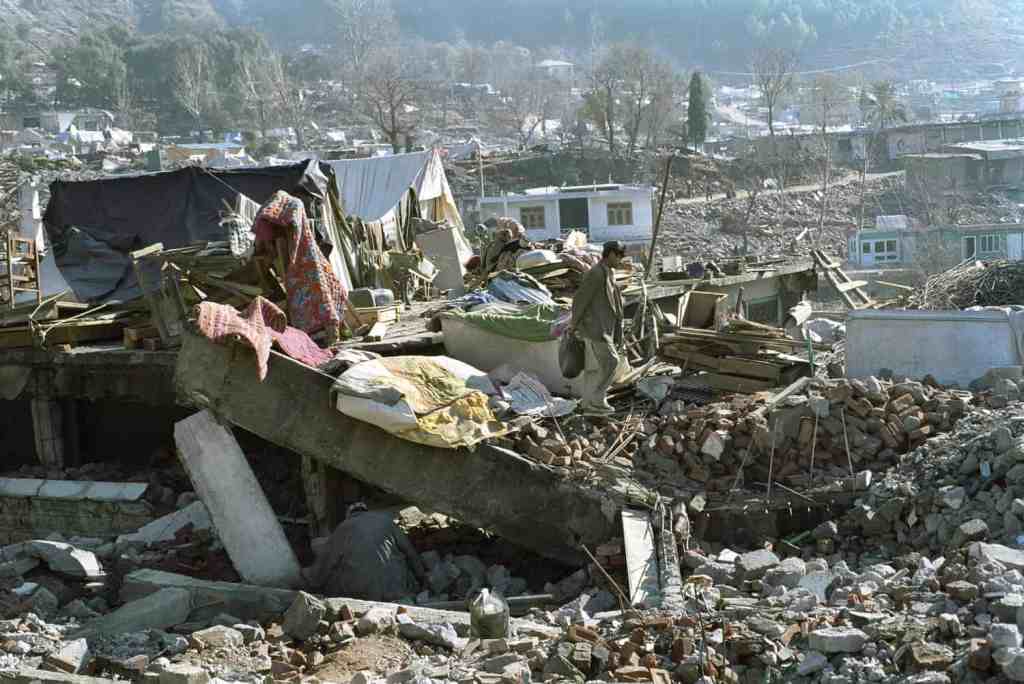

The 2005 Kashmir Earthquake took more than 80,000 lives and is among the deadliest on record worldwide.

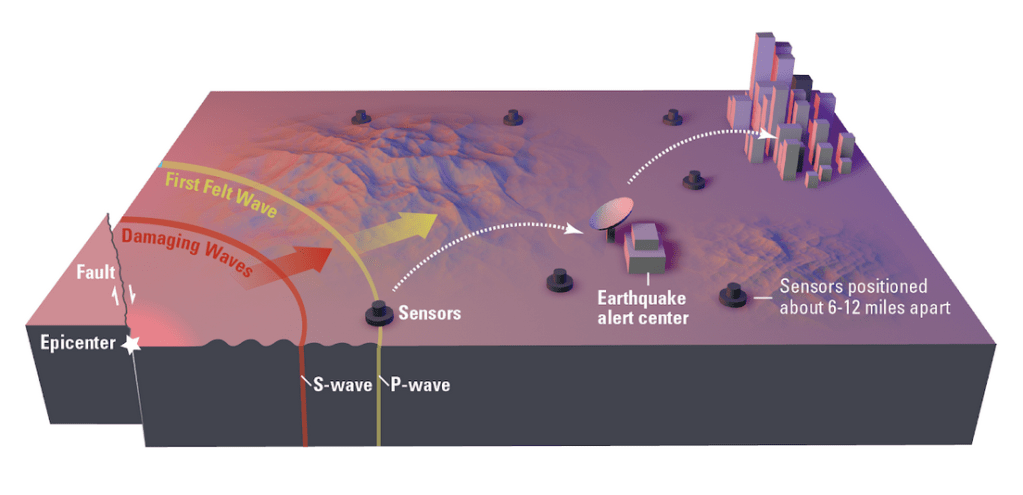

Much of the country’s built environment remains unsafe. Urban development continues with limited oversight, outdated codes, and widespread non-compliance. In rural areas, informal construction using poor-quality materials is still common. Hospitals, schools, and apartment complexes often lack structural reinforcement and are vulnerable to collapse during moderate or severe seismic activity. This systemic neglect extends to emergency services. Fire departments and ambulance networks are under-equipped. Rescue teams are often untrained for large-scale disaster response. Most concerning, there is still no functioning earthquake early warning system capable of alerting the population before strong ground motion begins.

There are opportunities to correct course. High-quality building standards must be enforced through clear regulation and routine inspection. Emergency services require professional development, adequate funding, and strategic coordination. Regional cooperation with countries that have faced similar challenges, particularly China, can provide a framework for retrofitting unsafe infrastructure and adopting modern seismic engineering practices. Through targeted collaboration under initiatives such as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, Pakistan can pursue not only economic development but also disaster resilience.

This article outlines the scale of Pakistan’s geological risk, assesses the country’s current state of infrastructure and disaster preparedness, and identifies policy steps to reduce long-term human and economic costs. Without deliberate investment and reform, the consequences of the next major earthquake could far exceed the damage of the last.

Geological Risk and Seismic Vulnerability

Pakistan is home to a dense network of fault lines that are capable of producing significant earthquakes.

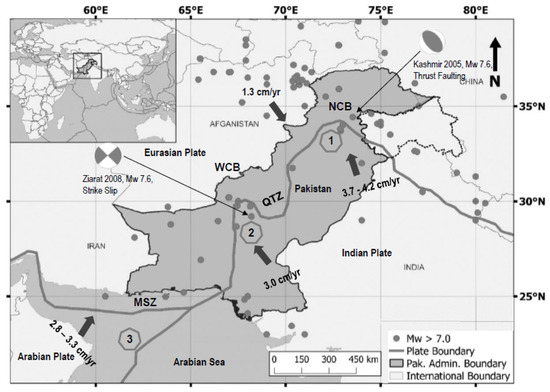

Pakistan is located where the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates collide. This collision is not only responsible for shaping the towering mountain ranges of the Himalayas, Hindu Kush, and Karakoram, but also for creating a dense network of fault lines that crisscross the region. These faults are capable of producing earthquakes of significant magnitude, including events strong enough to cause widespread destruction across cities and remote areas alike.

Nanga Parbat, the 9th tallest in the world, is a result of the collision of the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates.

Among the most prominent fault systems in Pakistan is the Chaman Fault in Balochistan, which extends for hundreds of kilometers along the western border. Northern Pakistan is shaped by the Main Mantle Thrust, a massive fault line associated with some of the strongest earthquakes in the region’s history. The Salt Range and Hazara Fault zones further complicate the seismic landscape, increasing the vulnerability of both urban and rural areas.

Several major cities sit within or near these zones. Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Lahore, Karachi, Quetta, and Muzaffarabad are all exposed to varying degrees of seismic risk. In addition, mountainous regions such as Gilgit-Baltistan, Azad Kashmir, and parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa face elevated risk due to their proximity to active thrust faults and their difficult terrain, which complicates rescue and relief efforts after any disaster.

The 1935 Quetta earthquake, which killed an estimated 30,000 people, remains one of the deadliest in South Asian history. More recently, the 2005 Kashmir earthquake measured 7.6 in magnitude and devastated entire districts, collapsing buildings, burying schools, and crippling essential infrastructure. These events are not isolated. Pakistan regularly experiences low to moderate magnitude earthquakes that serve as constant reminders of the seismic threat. However, public awareness of this geological reality remains limited, and planning policies often fail to reflect the level of risk.

Seismologists warn that future earthquakes in Pakistan could reach magnitudes of 8.0 or higher, especially in the northern regions where strain continues to accumulate along locked faults. The combination of densely populated urban centers, weak infrastructure, and complex terrain makes this not just a geological issue, but a national emergency in waiting.

Building Standards and Infrastructure Challenges

Pakistan’s construction landscape is dominated by informal development. A significant portion of the population, estimated to be well over sixty percent, lives in housing that was never formally approved, engineered, or inspected. Entire neighborhoods in cities like Karachi, Lahore, and Rawalpindi have emerged through unregulated expansion, often built on privately owned parcels without formal land titles, zoning review, or geological assessment. These communities grow outward and upward based on immediate shelter needs and financial constraints, not safety or structural planning.

Over sixty percent of Pakistan lives in housing that was never formally approved, engineered, or inspected.

In many of these cases, the land belongs to individuals or families who subdivide and sell plots without involving municipal authorities. Buildings are constructed with little or no professional oversight, frequently using laborers without formal training. The result is a nationwide pattern of low-resilience construction that offers little protection against seismic activity.

Concrete is the most commonly used material, but the quality is highly inconsistent. In small-scale projects, it is often mixed on-site without precise ratios, sometimes using substandard sand or gravel. Reinforcement with steel, which is essential for seismic resistance, is either skipped entirely or installed incorrectly. Many structures lack foundational integrity and are not anchored to withstand lateral shaking. The collapse of such buildings during an earthquake often leads to “pancake” failures, where floors fall on top of each other, making rescue efforts difficult and fatality rates high.

Formal building codes do exist. Pakistan’s Building Code 2007, developed with input from international experts, includes seismic provisions. However, enforcement is weak, especially outside of elite urban enclaves or large-scale commercial projects. Inspections are sporadic and often susceptible to corruption. Builders frequently bypass the system entirely, and even permitted projects may use lower-quality materials or cut corners in execution.

Geological assessments are almost never conducted for residential developments, even in high-risk zones. Most cities lack mandatory requirements for soil testing or seismic risk evaluation, and zoning regulations, where they exist, are often ignored. The Geological Survey of Pakistan produces hazard maps and conducts field research, but these findings are rarely integrated into urban planning or infrastructure design.

This lack of planning extends beyond private property. Critical public infrastructure such as bridges, highways, overpasses, and drainage systems are also at risk. Many of these assets were constructed decades ago without modern seismic design considerations. Maintenance is irregular, and records of structural integrity are often incomplete or unavailable. Key transportation corridors could suffer extensive damage in a strong earthquake, cutting off emergency access and disrupting economic activity at a national level.

This lack of planning extends beyond private property. Critical public infrastructure such as bridges, highways, overpasses, and drainage systems are also at risk.

The experience of the Earthquake Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Authority (ERRA), created in the aftermath of the 2005 Kashmir earthquake, offered a brief window of reform. ERRA introduced better safety guidelines and directed reconstruction efforts in affected areas. However, its scope was limited to post-disaster response, and the systemic integration of its recommendations into long-term national policy never materialized.

Pakistan’s vulnerability lies in its institutional failure to regulate how and where the country is built. Without structural reform that links building practices to geological risk, much of the population will remain exposed to preventable harm. A seismic event does not need to be exceptionally strong to result in large-scale devastation when the buildings and roads are this weak.

Disaster Preparedness and Emergency Services

Pakistan’s ability to respond to major disasters remains far below what is expected for a country of its population and geographic vulnerability. Despite facing regular floods, earthquakes, and urban emergencies, its disaster response infrastructure is underfunded, under-equipped, and under-coordinated. In most large-scale emergencies, Pakistan has depended on international assistance for rescue operations, humanitarian aid, and post-disaster recovery. This dependence, while sometimes necessary, underscores a failure to build independent, sustainable domestic capacity.

Fire departments across the country operate with minimal budgets and outdated equipment. Personnel often lack modern training in fire suppression, hazardous materials handling, or structural collapse response. In smaller cities and rural districts, fire services are either symbolic or completely absent. Similarly, there are few organized urban search and rescue teams with the specialized training and tools needed to respond effectively to large-scale building collapses or complex disasters.

Pakistani Fire Brigades generally lack advanced equipment for Urban Search & Rescue, which is crucial in the aftermath of an earthquake.

Pakistan also lacks a nationwide inventory of heavy machinery dedicated to emergency use. Equipment such as cranes, excavators, and cutting tools is essential for rescuing survivors trapped in debris following an earthquake. However, these resources are not pre-positioned or maintained for disaster readiness. Where such machinery exists, it is typically part of private construction companies or underutilized municipal departments with no formal integration into emergency response planning.

Readily accessible and numerous heavy equipment is necessary to move debris for collapsed buildings.

Investing in heavy equipment would serve a dual purpose. These assets could be used not only during emergencies but also for everyday national development needs. Road construction, infrastructure repair, and housing development all require the same machinery. With trained operators and basic coordination protocols, this equipment could be a cornerstone of both long-term development and rapid disaster response.

Ambulance services are also lacking in capability. Most ambulances function only as transport vehicles and are not equipped with basic life support systems, oxygen supplies, or patient monitoring equipment. Few have trained paramedics on board. As a result, pre-hospital care during mass casualty events is limited, and many deaths occur before patients even reach a medical facility. Pakistan’s overall hospital capacity, measured in terms of beds per capita, remains inadequate. Public hospitals already struggle under routine demands, and most lack the emergency stockpiles or trauma care units needed to handle thousands of simultaneous injuries in a disaster scenario.

Most Pakistani ambulances function only as transport vehicles and are not equipped with basic life support systems, oxygen supplies, or patient monitoring equipment.

The country does not have a centralized emergency response system. There is no nationwide 911 equivalent for dispatching fire, medical, and rescue services. Coordination across provinces and agencies is slow, often delayed by jurisdictional confusion and poor communication infrastructure. Without an integrated command and control center, the early hours of any major emergency are marked by disorganization and inconsistent response.

The National Disaster Management Authority has attempted to improve this situation, particularly through planning exercises and post-disaster assessments. However, it lacks enforcement authority and the operational capacity to lead large-scale responses across provinces. Its role remains largely advisory, and its budget is limited compared to the scale of risk Pakistan faces.

A modern disaster response system would include more than just agencies and infrastructure. It would also involve trained people and rapid logistics. Pakistan needs a dedicated airlift capacity, including cargo planes and helicopters that can transport supplies, evacuate the injured, and reach remote areas. At present, these capabilities are largely dependent on the military, which is responsive but not structured for sustained civilian operations.

In addition, the country would benefit from a national volunteer corps. This could include university students, civil society members, and trained community volunteers ready to assist during emergencies. With basic instruction in first aid, search and rescue, and logistical support, such a network could provide immediate assistance during the critical first 72 hours after a disaster.

Pakistan cannot continue to treat disaster response as a reactive process that only begins after lives have already been lost. Preparedness requires planning, investment, and long-term political commitment. The tools and systems needed already exist elsewhere in the world. What remains is the willingness to implement them.

Economic and Human Cost of Inaction

The economic and human consequences of a major earthquake in Pakistan would be catastrophic. In a densely populated urban center such as Karachi, Lahore, or Rawalpindi, a strong seismic event could result in tens of thousands of deaths and injuries within minutes. Entire neighborhoods built without proper structural planning could collapse. Public infrastructure, including hospitals, schools, and transportation corridors, would be heavily damaged or destroyed. The initial human toll would be staggering, but the long-term consequences could be even more destabilizing.

Pakistan is already grappling with a range of development challenges, including poverty, underinvestment in healthcare and education, and limited institutional capacity. A major natural disaster would compound these problems, further weakening public services, disrupting economic activity, and delaying progress by years, if not decades. In many ways, Pakistan cannot afford even a single large-scale disaster of the kind its geological position makes increasingly likely.

Rebuilding after such an event would take years and require enormous financial resources. Past disasters have shown that recovery is not just a matter of replacing lost buildings. Roads, bridges, and utility lines must be reconstructed. Water and sanitation systems often fail. Schools and hospitals need to be rebuilt and restaffed. Businesses that lose their facilities or supply chains may never reopen. The cost of recovery, in both financial and social terms, far exceeds the cost of prevention.

Critical institutions would also be at risk. If key government offices, communication networks, or law enforcement facilities were damaged or disabled, response coordination would falter at the exact moment it is needed most. Loss of institutional functionality during a crisis undermines public confidence, hampers aid distribution, and leads to political instability.

The economic impact would ripple across all sectors. Manufacturing and services would be interrupted. Exports could decline. Foreign investment could slow or be withdrawn entirely due to perceptions of instability and inadequate infrastructure. Insurance markets, already underdeveloped in Pakistan, would not be able to absorb losses. For a country still striving to reach middle-income status, this kind of setback could lock in underdevelopment for another generation.

The loss of human life in such a scenario would be immense, and much of it preventable. Without retrofitting existing buildings, enforcing seismic codes, and identifying unsafe structures through audits and analysis, millions remain at risk in their homes, workplaces, and schools. Unless Pakistan acts proactively, it will remain in a cycle where the response to disaster always comes too late.

There is still time to change course. Investments in prevention, such as resilient infrastructure, urban planning tied to geological risk, and an empowered disaster management system, are not just protective measures. They are prerequisites for sustainable development. Without them, the cost of inaction will eventually come due, paid in both lives and lost potential.

Economic and Human Cost of Inaction

The economic and human consequences of a major earthquake in Pakistan would be catastrophic. In a densely populated urban center such as Karachi, Lahore, or Rawalpindi, a strong seismic event could result in tens of thousands of deaths and injuries within minutes. Entire neighborhoods built without proper structural planning could collapse. Public infrastructure, including hospitals, schools, and transportation corridors, would be heavily damaged or destroyed. The initial human toll would be staggering, but the long-term consequences could be even more destabilizing.

Pakistan is already grappling with a range of development challenges, including poverty, underinvestment in healthcare and education, and limited institutional capacity. A major natural disaster would compound these problems, further weakening public services, disrupting economic activity, and delaying progress by years, if not decades. In many ways, Pakistan cannot afford even a single large-scale disaster of the kind its geological position makes increasingly likely.

Rebuilding after such an event would take years and require enormous financial resources. Past disasters have shown that recovery is not just a matter of replacing lost buildings. Roads, bridges, and utility lines must be reconstructed. Water and sanitation systems often fail. Schools and hospitals need to be rebuilt and restaffed. Businesses that lose their facilities or supply chains may never reopen. The cost of recovery, in both financial and social terms, far exceeds the cost of prevention.

Critical institutions would also be at risk. If key government offices, communication networks, or law enforcement facilities were damaged or disabled, response coordination would falter at the exact moment it is needed most. Loss of institutional functionality during a crisis undermines public confidence, hampers aid distribution, and leads to political instability.

The economic impact would ripple across all sectors. Manufacturing and services would be interrupted. Exports could decline. Foreign investment could slow or be withdrawn entirely due to perceptions of instability and inadequate infrastructure. Insurance markets, already underdeveloped in Pakistan, would not be able to absorb losses. For a country still striving to reach middle-income status, this kind of setback could lock in underdevelopment for another generation.

The loss of human life in such a scenario would be immense, and much of it preventable. Without retrofitting existing buildings, enforcing seismic codes, and identifying unsafe structures through audits and analysis, millions remain at risk in their homes, workplaces, and schools. Unless Pakistan acts proactively, it will remain in a cycle where the response to disaster always comes too late.

There is still time to change course. Investments in prevention, such as resilient infrastructure, urban planning tied to geological risk, and an empowered disaster management system, are not just protective measures. They are prerequisites for sustainable development. Without them, the cost of inaction will eventually come due, paid in both lives and lost potential.

Investment in Prevention

For a country as seismically vulnerable as Pakistan, investment in prevention is not an option, it is an imperative. The risks posed by even a moderate earthquake in a densely populated area would be devastating. Yet most of the damage and loss of life that would result from such an event is preventable. The foundation of a serious prevention strategy must begin with enforcement. Pakistan’s seismic building codes, while technically present in law, are outdated and almost entirely unenforced across most of the country. New construction must be legally required to meet modern seismic standards, without exception. This obligation must apply to private homes, apartment complexes, commercial buildings, and public infrastructure alike. Provincial or local variation in enforcement cannot be tolerated, and compliance should be verified through legally mandated inspections tied directly to the issuance of occupancy permits, utility connections, and construction licenses.

At the same time, the millions of structures already standing across Pakistan must be systematically evaluated. All buildings in high-risk zones should undergo structural audits, with priority given to hospitals, schools, high-rise residential towers, and government buildings. The state must be prepared to fund or enforce retrofitting where necessary, and unfit structures should be vacated or rebuilt within fixed timelines. This process must not be left to the private market alone. Local governments, engineering associations, and urban planning departments should be tasked with executing this work under a unified national mandate, with results tracked in a centralized, publicly accessible database.

Infrastructure must be treated with the same urgency. The failure of a major bridge, overpass, or roadway during an earthquake does not simply cause damage. It blocks emergency access, cuts off supply routes, and delays rescue operations when time is critical. A national review of seismic vulnerability in transport and utility infrastructure must be undertaken, and projects for strengthening, rebuilding, or replacing unsafe segments should be launched without delay.

In the event of a major disaster, 72-hour emergency survival kits serve as a stop-gap measure until further aid is able to arrive.

Preparedness also requires direct outreach to the public. Every household in Pakistan should have access to a 72-hour emergency survival kit. These kits should include shelf-stable food, water purification tools, flashlights, first aid materials, radios, and protective gear. Their distribution must be accompanied by nationwide public education campaigns on earthquake awareness, evacuation procedures, and emergency behavior. These programs should be integrated into school curricula, local media, religious institutions, and community groups to ensure broad cultural penetration and practical relevance.

At the core of a prevention-focused strategy must be the creation or transformation of an institution that can coordinate and enforce all of these activities. Pakistan’s existing National Disaster Management Authority, while active in recovery and planning, lacks the operational authority, funding, and integration to lead a comprehensive national effort. Rather than replacing it, Pakistan should restructure and expand the NDMA into a fully empowered Office of Emergency Response and Management. This agency should operate with direct executive authority and be granted sufficient budgetary and logistical capacity to manage national disaster readiness. It would oversee not only emergency response operations but also structural inspections, rescue coordination, and long-term preparedness programs.

One of its most critical tasks must be the professionalization and expansion of Pakistan’s fire and rescue services. At present, fire departments across the country lack modern vehicles, breathing apparatuses, fire-resistant gear, and tools for structural collapse response. Most departments operate with limited personnel and training, and some areas lack fire coverage entirely. Rescue services are even less developed, with little capacity to carry out complex search operations or provide immediate trauma care. A serious national program must be launched to staff, train, and equip fire and rescue services in all major urban and high-risk regions. These departments must be supplied with dual-use heavy equipment, such as cranes, loaders, and cutting machines, that serve both everyday development needs and emergency response. Equipment alone is not enough. Operators must be recruited and trained on an ongoing basis, with centralized records, certifications, and coordinated deployment protocols.

Ambulance services must also be brought into the modern era. Most ambulances in Pakistan serve only as transport vehicles with minimal or no life support equipment. A national standard should be established for basic and advanced life support ambulances, along with the training of emergency medical technicians and paramedics. Emergency services must be made accessible through a centralized, nationwide emergency call system that links medical, fire, and rescue dispatch to a unified command and control center. This system should be capable of real-time coordination across provincial and district lines, ensuring that help is sent where it is needed most, without bureaucratic delay or miscommunication.

Pakistan must build up its logistical capacity for emergencies. A larger dedicated fleet capable of transporting aid, equipment, and personnel to disaster zones within hours.

Finally, Pakistan must build up its logistical capacity for national-scale emergencies. A dedicated fleet of cargo aircraft and helicopters should be acquired or placed under dual civilian-military use, capable of transporting aid, equipment, and personnel to disaster zones within hours. These air assets are critical for reaching remote or cut-off areas, conducting medical evacuations, and distributing emergency supplies. In parallel, a standing national volunteer corps should be established. This body would be drawn from university students, community groups, and civil society organizations, and trained in basic disaster response, logistics, and first aid. Volunteers could be rapidly mobilized in the aftermath of a disaster, supplementing official rescue efforts and bringing help to areas not yet reached by professional teams.

Pakistan has the human capital, technical knowledge, and basic institutional structure to pursue this transformation. What it lacks is the political will and national prioritization of disaster prevention. Earthquake resilience is not simply a matter of safety, it is a condition for economic growth, governance stability, and public confidence. Without a comprehensive prevention strategy that includes enforcement, retrofitting, institutional reform, and public readiness, Pakistan remains acutely exposed to a disaster that is not only foreseeable, but inevitable.

Pakistan–China Cooperation Opportunities

As Pakistan works to strengthen its disaster resilience, one of its most practical and strategic partners is China. With extensive experience in earthquake recovery, advanced seismic technology, and a shared border, China is uniquely positioned to assist Pakistan in developing the capacity to prevent, withstand, and respond to future disasters.

China has faced some of the most devastating earthquakes of the twenty-first century, including the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in Sichuan Province, which killed nearly 90,000 people and displaced millions. In the aftermath, China carried out one of the most comprehensive post-disaster reconstruction efforts in the world, incorporating cutting-edge seismic-resistant design, rapid deployment of rescue teams, and the development of large-scale early warning systems. Pakistan can and should learn directly from this experience.

At the technical level, Chinese engineering and construction firms now follow strict seismic safety standards, using reinforced structural systems and soil-anchoring technologies that have proven effective in high-risk zones. Through partnerships under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), these practices can be transferred and integrated into infrastructure projects in Pakistan. New roadways, bridges, public buildings, and energy installations built with Chinese cooperation must be held to the same seismic standards used in China’s own high-risk areas.

Earthquake Early Warning systems, such as the one in California, provide a crucial few seconds for preparation. A joint Pakistan–China effort to build a regional seismic monitoring and alert network could dramatically improve Pakistan’s readiness.

Beyond construction, China is a global leader in earthquake early warning systems. Its seismic sensor networks detect ground movement in real time, allowing authorities to trigger alerts seconds before damaging waves arrive. In a major earthquake, even a brief warning can shut down industrial machinery, stop trains, close gas lines, and allow people to take cover. Pakistan has no such system in place. A joint Pakistan–China effort to build a regional seismic monitoring and alert network could dramatically improve Pakistan’s readiness and potentially extend coverage to areas across Central and South Asia.

Collaboration should not be limited to hardware and construction. Training programs for Pakistani engineers, urban planners, emergency responders, and policymakers can be established in partnership with Chinese institutions. Pakistani professionals can study China’s integrated approach to disaster preparedness, including how it links planning, technology, public education, and institutional enforcement. In return, Pakistani manpower, especially skilled and semi-skilled labor, could contribute to Chinese-led infrastructure projects across the region, creating mutual value and deepening institutional ties.

Coordination in times of crisis is another key area of opportunity. China’s western provinces are directly connected to northern Pakistan via the Karakoram Highway and land corridors through Gilgit-Baltistan. This proximity allows for rapid mobilization of Chinese aid and technical support in the event of a major disaster. China also maintains a large air fleet, including cargo planes and helicopters, that can transport supplies and rescue teams quickly across the border. Establishing pre-agreed protocols for cross-border disaster assistance would ensure that help can flow without delay when it is needed most.

Finally, cooperation with China should include long-term planning and funding strategies. Joint financing mechanisms could support the retrofitting of vulnerable infrastructure in Pakistan, particularly in schools, hospitals, and government buildings. Chinese development banks and construction firms are already active in Pakistan through CPEC. With clear policy alignment, these actors could play a critical role in strengthening Pakistan’s seismic resilience at scale.

Pakistan must approach this cooperation not as a one-sided dependency but as a strategic partnership. By aligning its disaster preparedness goals with China’s technological and logistical strengths, Pakistan can accelerate the development of a national system that is modern, responsive, and regionally integrated. In doing so, it can transform its current vulnerabilities into a foundation for resilience and mutual growth.

Local Responsibility and the Path Forward

Earthquake preparedness in Pakistan requires action at every level. Local and provincial governments must adopt risk-sensitive urban planning, enforce building codes, and strengthen emergency services. These are the front lines of prevention, where policy becomes practice.

Civil society plays a vital role in raising awareness, training volunteers, and holding institutions accountable. Public engagement can drive the demand for safer construction, better planning, and stronger response systems.

The risk Pakistan faces is not hypothetical. It is immediate and growing. The country must modernize its construction practices, expand emergency capacity, and pursue serious cooperation with partners like China. Earthquake resilience is not just a safety measure, it is essential to national stability and development.

The danger is real. The time to act is now.