Agriculture remains the backbone of Pakistan’s economy, yet the sector shows persistent signs of stagnation. According to the Pakistan Economic Survey 2022–23, agriculture contributed 19.4% to GDP and employed ~37.4% of the labor force, making it the largest source of livelihood for rural communities . Broadly, it supports two-thirds of the population either directly or indirectly through farming, livestock, and related industries .

Despite this centrality, the sector’s growth is slowing. Over the past decade, agricultural growth has averaged 1.5–2.0% annually, lagging behind Pakistan’s population growth of ~2.1% . This imbalance means agricultural output is not keeping pace with rising demand, creating structural vulnerabilities in food security.

The sector’s underperformance is not merely an economic issue but a national security concern. Without significant reforms, Pakistan risks falling further into import dependency for essential staples such as wheat, pulses, and edible oils, exposing millions to price shocks and supply disruptions.

Current State of Pakistani Agriculture:

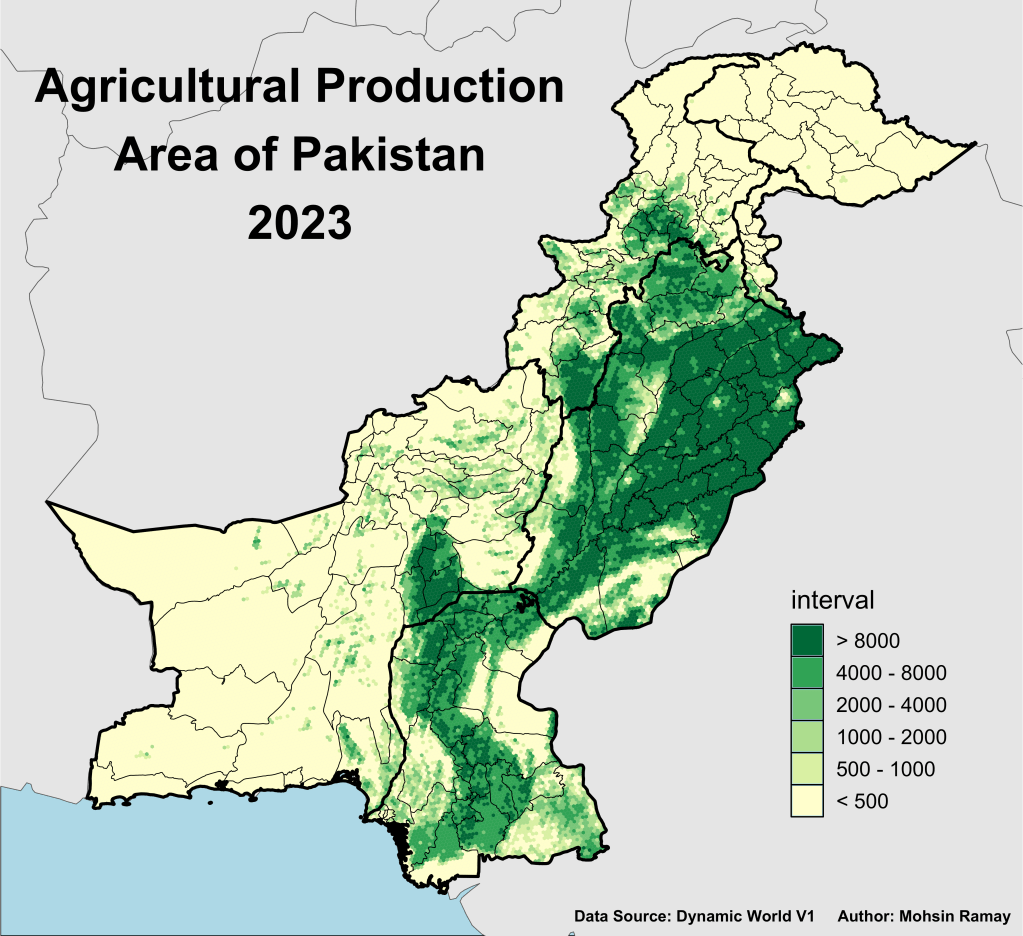

Pakistan’s agricultural landscape covers an immense share of the country’s territory. Out of 79.6 million hectares of total land area, roughly 22 million hectares are cultivated, representing about 27% of total land . Of this, nearly 80% of cultivated land is irrigated through the Indus Basin Irrigation System, one of the largest in the world (World Bank 2021). By comparison, India cultivates around 160 million hectares, while Egypt, despite its smaller size, achieves higher per-acre productivity due to intensive irrigation and modern technology (FAO 2022). Pakistan’s reliance on traditional cropping systems, coupled with uneven yields, underscores both the scale and inefficiency of its agricultural base.

Pakistan’s agricultural landscape covers an immense share of the country’s territory. Out of 79.6 million hectares of total land area, roughly 22 million hectares are cultivated, representing about 27% of total land .

Major Crops and Production Levels:

Wheat remains Pakistan’s dominant staple, occupying over 8.5 million hectares (≈40% of total cropped area). The 2022–23 season saw a record harvest of 27.6 million tonnes, yet domestic consumption stood at 30–31 million tonnes, leaving a gap of 3–4 million tonnes that had to be bridged through imports (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2023). By comparison, India harvested 110 million tonnes in the same period, while the United States produced about 44 million tonnes, both with higher per-acre productivity. Pakistan’s average wheat yield is 3.1 tonnes/hectare, significantly lower than the global average of 3.5–4.0 tonnes/hectare.

Rice is the second most important staple, cultivated on 3.3 million hectares, producing around 7.3 million tonnes in 2022–23, including the globally renowned basmati variety. Around 4.5–5 million tonnes were exported, generating between $2.5–3 billion in foreign exchange earnings (State Bank of Pakistan, 2023). Despite its export success, Pakistan’s per-hectare rice yield lags behind China, where yields average 6.9 tonnes/hectare, nearly double Pakistan’s 3.5 tonnes/hectare (FAO 2022).

Cotton, once Pakistan’s “white gold,” has seen dramatic decline. Production fell from 13–14 million bales in 2014 to just 5 million bales in 2020–21, due to pest infestations, climate variability, and policy neglect. A partial recovery was seen in 2022–23, with output reaching 9.9 million bales, yet this remains far below historic highs. In contrast, India produced over 25 million bales in the same year, reflecting both larger acreage and stronger seed technology adoption (ICAC 2023).

Cotton, once Pakistan’s “white gold,” has seen dramatic decline. Production fell from 13–14 million bales in 2014 to just 5 million bales in 2020–21, due to pest infestations, climate variability, and policy neglect.

Sugarcane production in 2022–23 was about 82 million tonnes, making Pakistan the 5th largest producer globally. However, sugarcane is one of the most water-intensive crops, requiring up to 1,500–2,500 liters of water per kilogram of refined sugar (IWMI 2021). In a water-scarce country, this represents a severe misallocation of resources.

Maize has grown in importance, particularly for the poultry and feed industry. Pakistan harvested around 10 million tonnes in 2022–23 on 1.6 million hectares, with average yields of 6 tonnes/hectare—a relative success compared to wheat and rice. Neighboring China, however, produces over 280 million tonnes annually, underscoring the gap in scale and research investment.

When it comes to fruits and vegetables, Pakistan is a leading producer of mangoes, citrus, and potatoes. Mango production is estimated at 1.7 million tonnes, with Pakistan ranking among the top five producers globally. Citrus (primarily kinnow) production stands at 2.4 million tonnes, while potatoes reach about 5.0 million tonnes annually. Yet post-harvest losses remain severe, with 30–40% of fruit and vegetable output wasted due to poor cold storage and transport infrastructure (FAO 2021).

Livestock and Dairy:

Beyond crops, livestock is the single largest contributor to agricultural GDP, accounting for nearly 60% of the sector’s value added (Pakistan Economic Survey 2023). Milk production has reached 65 billion liters annually, making Pakistan the 4th largest milk producer in the world. Meat production is around 4.9 million tonnes, largely driven by poultry and cattle. However, less than 10% of milk is processed into value-added products, compared to over 90% in developed economies. This low level of processing not only restricts domestic nutrition outcomes but also limits Pakistan’s ability to export dairy products competitively.

Pakistan is the 4th largest global producer of milk.

The dominance of low-productivity crop farming, inefficient water use, and underdeveloped value chains paints a stark contrast with Pakistan’s potential. While the country possesses vast arable land and favorable agro-ecological zones, its productivity per acre lags significantly behind regional and global benchmarks. Without substantial modernization, Pakistan risks becoming increasingly reliant on imports to feed a population that continues to expand rapidly.

Food Self-Sufficiency & Deficits:

The ability of a country to feed its people affordably rests on generating consistent surpluses of staple foods. Surpluses drive down costs through economies of scale, provide buffers against shocks, and allow for exports that earn foreign exchange. Conversely, deficits not only raise prices domestically but also make nations vulnerable to volatility in global markets. Pakistan’s agricultural balance sheet demonstrates the urgency of this challenge: while the country produces significant quantities of food, the deficits in key staples are widening, and even where surpluses exist, they are undermined by waste and inefficiency.

Wheat: A Chronic Deficit:

Wheat is Pakistan’s most critical food staple, accounting for over one-third of caloric intake. Yet production consistently falls short of national demand. In 2022–23, Pakistan produced 27.6 million tonnes, against a domestic requirement of 30–31 million tonnes (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2023). This 10–15% gap forces Pakistan to import wheat annually, often 2–3 million tonnes, exposing the economy to global price volatility, as seen during the Ukraine war when wheat prices surged by over 30% worldwide. For low-income households, which spend 50–60% of their income on food, even minor price increases in wheat translate into severe food insecurity (World Bank, 2022). Closing this gap through yield improvements could not only reduce reliance on imports but also stabilize domestic food prices.

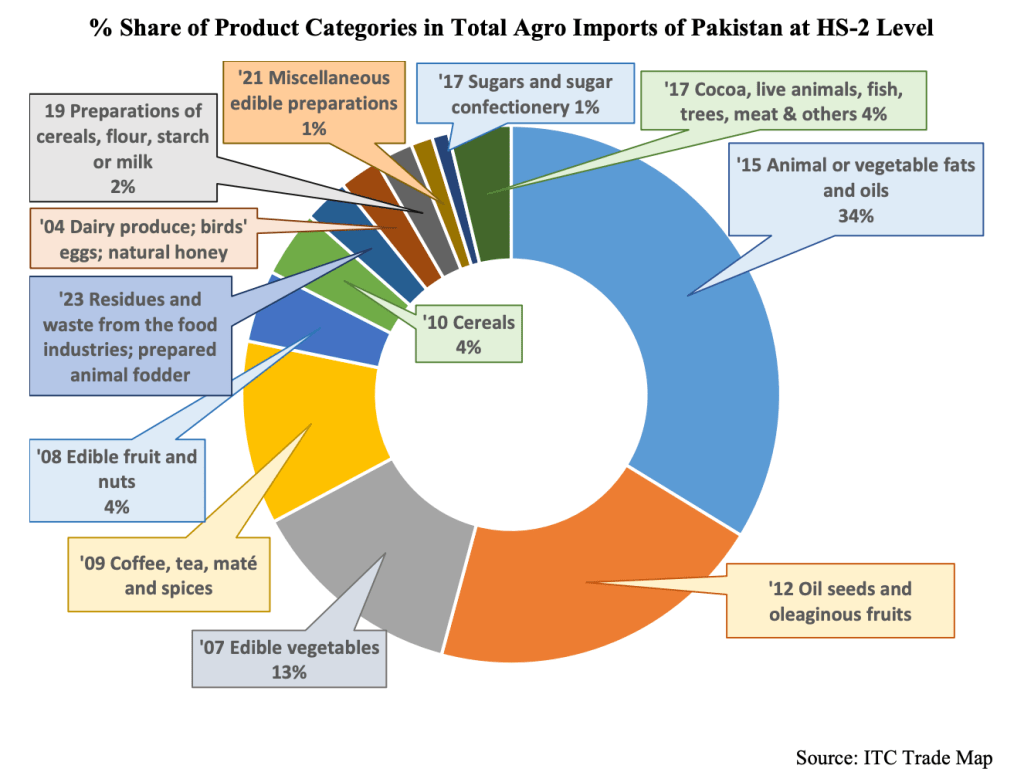

Edible Oil: The Largest Import Burden:

Pakistan imports 85–90% of its edible oil needs, translating to an import bill of roughly $4 billion annually (State Bank of Pakistan, 2022). This dependence is staggering when viewed against the country’s balance of payments crisis. Palm oil, imported primarily from Malaysia and Indonesia, accounts for most of this demand. With global vegetable oil markets highly volatile, Pakistan’s heavy reliance leaves it at the mercy of international supply chains. Substituting even a portion of imports with domestic oilseeds, such as sunflower, canola, or soybean, could ease pressure on the current account and provide a new avenue for farmer income diversification.

Pakistan imports 85–90% of its edible oil needs, translating to an import bill of roughly $4 billion annually (State Bank of Pakistan, 2022).

Pulses: A Neglected Necessity:

Despite being a protein-rich staple for low- and middle-income households, 70–80% of pulses are imported (FAO, 2022). Domestic cultivation has been squeezed out by cash crops like sugarcane and wheat, both of which receive heavy subsidies. Pakistan imports over 1 million tonnes of pulses annually, primarily from Canada and Australia. A targeted program to expand pulse production on marginal lands could reduce this dependence while simultaneously improving nutrition outcomes.

Fruits and Vegetables: Wasted Surpluses:

On paper, Pakistan produces an abundance of fruits and vegetables: 1.7 million tonnes of mangoes, 2.4 million tonnes of citrus, and 5 million tonnes of potatoes annually. However, 30–40% of this output is lost post-harvest due to inadequate storage, transportation, and processing facilities (FAO, 2021). These losses represent not only wasted nutrition but also billions of rupees in foregone farmer income. Building cold chain logistics and agro-processing industries could transform this surplus into both affordable domestic food and competitive exports.

Pakistan’s Nutrition Crisis:

Despite abundant farmland and agricultural output, Pakistan suffers from a deep nutrition crisis. According to the National Nutrition Survey (2018), 40% of children are stunted, 18% suffer from wasting, and 28% are underweight. This paradox highlights the disconnect between food availability, food affordability, and nutritional quality. Heavy reliance on wheat and sugar-based diets, combined with inadequate access to proteins, pulses, and vegetables, contributes to widespread malnutrition. The costs are long-term: stunted children are more likely to face poor educational outcomes, reduced productivity, and health complications, perpetuating cycles of poverty.

Implications for Food Security:

The combined deficits in wheat, pulses, and edible oil, together with the large-scale waste of fruits and vegetables, reveal a deep structural imbalance in Pakistan’s food system. Without meaningful reform, the country will remain vulnerable to global market shocks such as sudden increases in wheat or oil prices, which can raise household food costs almost overnight. These deficits also create massive foreign exchange drains, with billions of dollars spent each year on food imports that put additional pressure on an already fragile balance of payments. Within Pakistan, the burden falls most heavily on the poor, since low-income families often spend more than half of their income on food and are forced to make painful choices between nutrition, health, and other essential needs when prices rise. The pathway to resilience lies not only in increasing production but in strategically reducing deficits in staples such as wheat, pulses, and oilseeds, while also investing in storage and processing systems to curb the waste of perishable fruits and vegetables. If these reforms are carried out, Pakistan could move toward true self-sufficiency, generate surpluses that stabilize prices, and ensure that affordable food is available to all citizens. Food security in this context must be understood not only as producing more but as producing smarter, with an emphasis on sustainability, nutrition, and long-term resilience.

Pakistan’s Agricultural Structural Weaknesses:

Outdated Farming Methods:

Pakistan’s agricultural base is constrained by outdated farming practices that waste resources and suppress productivity. Nearly ninety percent of irrigation is carried out through traditional flood methods, leading to water use efficiency as low as thirty to thirty-five percent (World Bank, 2021). With per capita water availability already below 1,000 cubic meters, this inefficiency represents one of the most serious threats to national food security. Mechanization levels are also strikingly low, with only 0.9 tractors per 100 hectares compared to more than four in India and over ten in advanced economies such as the United States and France (FAO, 2022). The limited adoption of high-yield seed varieties further compounds the problem. Wheat, Pakistan’s most important crop, averages only 3.1 tonnes per hectare, while the global average is 3.5 to 4 tonnes and the United States averages 3.9 tonnes. If Pakistan achieved yields equivalent to the OECD average, national wheat output could increase by nearly 5 million tonnes per year. This single improvement would eliminate the current wheat deficit and reduce annual import bills by more than a billion dollars. The cost of outdated methods is therefore not abstract: it translates directly into lost revenue, greater vulnerability to food crises, and diminished nutrition for millions of citizens.

Land Fragmentation:

Land fragmentation is another obstacle that keeps productivity low. The average farm size in Pakistan is only 2.6 hectares, and more than sixty percent of farms are under five hectares (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2023). Farms of this size are uneconomical to mechanize and cannot afford modern irrigation or storage facilities. Smallholder farmers are left dependent on traditional labor-intensive practices, and their limited market power leaves them vulnerable to exploitation by middlemen. In advanced agricultural economies, average farm sizes are many times larger, and farmers operate within integrated systems that provide credit, crop insurance, and extension services. If Pakistan’s fragmented landholdings could be consolidated or supported through cooperative models, the country could unlock economies of scale that would sharply improve yields. For example, even a modest twenty percent increase in yields across major crops would raise national agricultural output by more than ten million tonnes annually, providing both food surpluses and significant export potential.

Policy and Market Failures:

Agricultural policy further entrenches inefficiency by directing the bulk of subsidies toward wheat and sugarcane. Both crops are politically sensitive but resource intensive, especially sugarcane, which consumes up to 2,500 liters of water for every kilogram of refined sugar (IWMI, 2021). Meanwhile, essential crops such as pulses and oilseeds, which Pakistan imports at a combined cost of over five billion dollars annually, are neglected. Access to agricultural credit remains heavily skewed, with only twenty to twenty-five percent of farmers able to access formal financing (State Bank of Pakistan, 2022). The majority rely on informal lenders who charge exorbitant interest rates, locking farmers into cycles of debt.

Relying on markets alone to correct these distortions has proven inadequate. Farmers naturally gravitate toward crops that offer immediate profitability or government support, rather than those critical for national food security. By contrast, advanced agricultural economies such as France, Japan, and the United States maintain large-scale state-supported systems that ensure surpluses in strategic crops, subsidize innovation, and stabilize rural incomes. The absence of such structural guidance in Pakistan leaves its agricultural sector vulnerable to both climate shocks and international price volatility.

Broader Implications:

The consequences of these weaknesses are visible in every layer of society. Outdated irrigation wastes scarce water resources and reduces yields, directly worsening food inflation and rural poverty. Low mechanization suppresses labor productivity and locks millions into subsistence farming. Policy distortions ensure that billions are spent on imports for items that could be produced domestically, draining foreign exchange reserves. Most critically, malnutrition remains widespread, with more than forty percent of children stunted and nearly one-third of the population undernourished (National Nutrition Survey, 2018). If Pakistan had yields equivalent to OECD averages across its major crops, the country would not only be self-sufficient in wheat, pulses, and edible oils but could also generate exportable surpluses worth billions annually. The failure to modernize is therefore not only an economic issue but one of human survival and national resilience.

Environmental and Pollution Challenges

Water Scarcity

Water scarcity is the most critical constraint facing Pakistan’s agriculture. In 1951, per capita water availability stood at 5,260 cubic meters. Today, it has fallen to around 900 cubic meters, placing Pakistan well below the United Nations’ threshold of 1,000 cubic meters that defines a water-scarce country (World Bank, 2021). Agriculture consumes between 90 and 93 percent of available freshwater, much of it squandered through inefficient flood irrigation systems that lose more water than they deliver to crops. The Indus Basin Irrigation System, one of the largest in the world, is under immense stress from over-extraction, poor maintenance, and uneven distribution. Groundwater reserves, which have served as a buffer against canal shortages, are being depleted at alarming rates, especially in Punjab and Sindh. With climate change further disrupting the flow of rivers fed by Himalayan glaciers, Pakistan is heading toward a severe crisis in which water scarcity will dictate not only crop choices but also national survival.

Soil Degradation

The health of Pakistan’s soils is deteriorating rapidly, undermining both yields and long-term sustainability. Around 6.3 million hectares, nearly one-fourth of cultivated land, are affected by salinity and waterlogging, the result of poor irrigation practices and inadequate drainage (Pakistan Agricultural Research Council, 2022). Over-reliance on nitrogen-based fertilizers has further degraded soil fertility, leading to nutrient imbalances that depress productivity. Farmers often apply urea in excessive quantities because it is subsidized, while neglecting micronutrients essential for plant health. The consequence is a slow but steady decline in soil capacity, which reduces yields year after year and increases dependence on external inputs. If left unaddressed, this degradation will permanently erode Pakistan’s ability to feed its population, forcing even greater dependence on food imports.

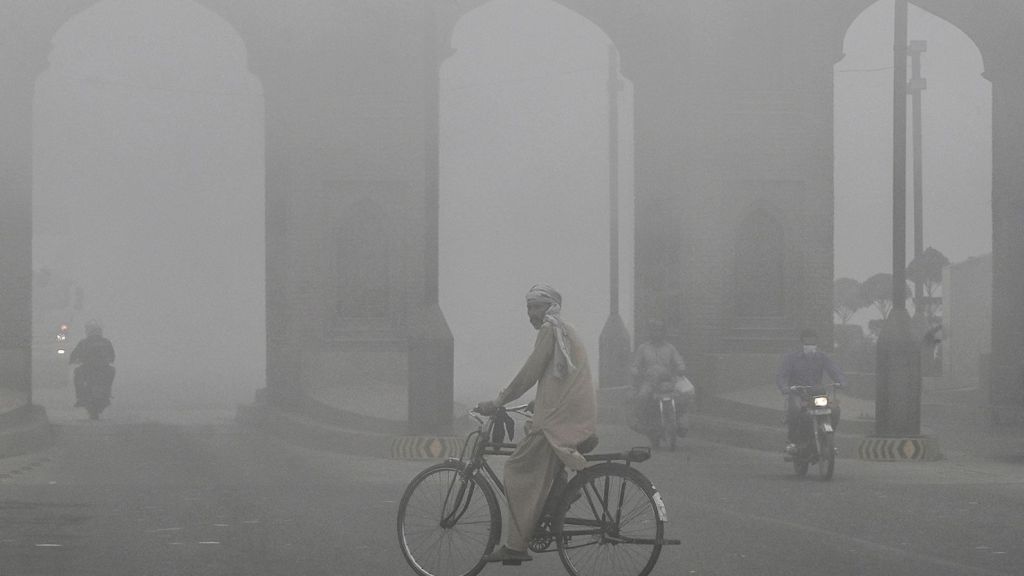

Pollution and Smog

Pakistan’s agricultural productivity is also undermined by pollution, particularly in Punjab where industrial emissions, vehicle exhaust, and crop residue burning combine to create dense winter smog. This smog not only affects human health but also reduces sunlight penetration, disrupting photosynthesis and slowing crop growth. Studies indicate that persistent smog during the wheat-growing season can lower yields by up to 5 percent (FAO, 2020). Airborne heavy metals and fine particulate matter settle onto crops and soils, altering their composition and in some cases making food less safe for consumption. The intersection of urban pollution and rural agriculture creates a vicious cycle: industrialization proceeds without environmental regulation, and farmers pay the price through lower productivity and reduced incomes.

Climate Change

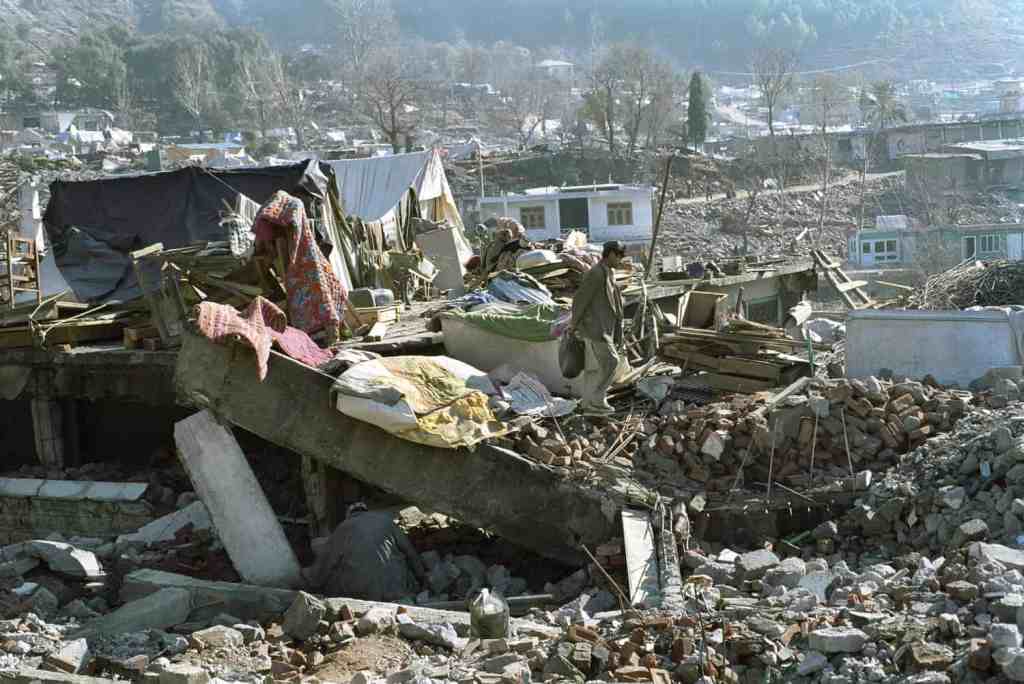

Overlaying these structural challenges is the broader threat of climate change, to which Pakistan is acutely vulnerable. The Global Climate Risk Index ranks Pakistan as the eighth most affected country in the world. The 2022 floods alone caused an estimated 3.7 billion dollars in agricultural losses, wiping out crops across millions of hectares and devastating rural livelihoods (World Bank, 2023). In addition to catastrophic floods, Pakistan faces recurrent heatwaves that cut wheat yields by 10 to 15 percent in affected districts, alongside erratic monsoon patterns that make planting seasons increasingly unpredictable. Glacier melt in the north poses another long-term risk, with the potential to disrupt river flows that sustain the Indus Basin. Together, these changes amount to a direct assault on Pakistan’s agricultural system, threatening both food supply and economic stability.

Pakistan’s 2022 floods alone caused an estimated 3.7 billion dollars in agricultural losses, wiping out crops across millions of hectares and devastating rural livelihoods.

Implications

These environmental and pollution challenges are not isolated problems but interlocking crises that magnify one another. Water scarcity drives farmers to overexploit groundwater, which worsens salinity and soil degradation. Pollution reduces crop yields while contributing to climate change through unchecked emissions. Climate shocks, whether floods or heatwaves, undo years of incremental progress and deepen rural poverty. If Pakistan’s agricultural system were supported by the infrastructure, technology, and regulatory frameworks of a developed economy, much of this vulnerability could be mitigated. Advanced irrigation methods could conserve scarce water, balanced fertilizer regimes could restore soil health, and environmental enforcement could limit the impact of smog. In Pakistan’s current system, however, these issues accumulate unchecked, imposing billions of dollars in annual losses and threatening the very foundation of national food security.

Opportunities for Agricultural Revamp

Despite the severity of Pakistan’s agricultural challenges, the sector holds immense potential for transformation. With the right policies, technology, and infrastructure, Pakistan could not only meet domestic food demand but also emerge as a competitive exporter in high-value crops. The opportunity lies in shifting from outdated, low-yield practices toward a modernized, diversified, and climate-resilient agricultural system.

Modernization and Technology

The modernization of farming practices is essential if Pakistan is to close its productivity gap with other countries. Precision agriculture, incorporating drones, geographic information systems (GIS), and artificial intelligence, can optimize water use, fertilizer application, and pest control. Countries like China and Brazil have already demonstrated how precision technologies raise yields while cutting input costs. Drip and sprinkler irrigation, which currently cover less than two percent of Pakistan’s cultivated area, could dramatically increase water efficiency. In India, where adoption rates are higher, farmers report water savings of up to fifty percent alongside yield gains of twenty to thirty percent (FAO, 2022). Similarly, mechanized sowing and harvesting could raise crop yields by twenty to thirty percent while reducing post-harvest losses. If applied nationwide, these technologies would not only close the wheat deficit but also allow Pakistan to generate consistent surpluses, ensuring affordable food while freeing billions currently spent on imports.

Crop Diversification

Another critical opportunity lies in diversifying Pakistan’s cropping pattern away from water-intensive and politically entrenched crops like sugarcane. On the export side, Pakistan has enormous potential to position itself as a global supplier of luxury agricultural products. Mangoes, kinnow citrus, and dates are already world-class in quality but lack proper branding and market penetration. With geographical indication (GI) protection for basmati rice and targeted marketing, Pakistan could command premium prices internationally, much like how Italy protects Parmesan cheese or Japan protects Kobe beef. High-value niche products such as organic vegetables, honey, and floriculture (roses and tulips) could also be promoted to tap into rapidly growing global markets.

For staples, diversification is equally critical. Pakistan currently spends more than four billion dollars annually importing edible oils and pulses. Expanding the cultivation of oilseeds such as sunflower, canola, and soybean, along with pulses like lentils and chickpeas, could sharply reduce this dependency. Even modest increases in domestic production would save hundreds of millions in foreign exchange each year. Introducing non-traditional crops such as quinoa and high-value maize hybrids would also diversify diets and open up new export streams.

Infrastructure and Value Chains

The weak infrastructure that underpins Pakistan’s agriculture is a major reason why surpluses fail to translate into affordable food or export revenue. Currently, less than ten percent of fruits and vegetables are transported with refrigeration, leading to post-harvest losses of thirty to forty percent (FAO, 2021). Rural road networks remain underdeveloped, raising transport costs and cutting farmer profitability. For perishable goods, poor connectivity alone accounts for losses equivalent to twenty to twenty-five percent of total output. In livestock and dairy, the problem is equally severe. Although Pakistan is the fourth-largest milk producer globally, only five to seven percent of its milk is processed into value-added products, compared to more than ninety percent in developed countries. The creation of modern cold chain networks, food processing facilities, and rural logistics hubs could cut waste in half while creating tens of thousands of jobs. If even one-third of wasted fruits and vegetables were saved through cold storage and processing, Pakistan could both improve domestic nutrition and generate hundreds of millions of dollars in exportable value.

Governance and Policy

Perhaps the most decisive factor is governance. For any agricultural overhaul to succeed, the state must first and foremost act with integrity, resisting the capture of agricultural policy by narrow political and business interests. Subsidies and state interventions must be redirected toward climate-resilient and economically strategic crops, not those that serve entrenched lobbies. A national seed policy ensuring the availability of certified high-yield and climate-resilient seeds could transform crop performance across the board. Expanding access to agricultural credit and insurance would allow smallholder farmers, who make up the majority of the sector, to invest in technology and withstand climate shocks. Finally, the creation of digital platforms that connect farmers directly to markets could reduce the thirty to forty percent margin currently captured by middlemen, ensuring that both farmers and consumers benefit from more efficient pricing.

Implications

The opportunities for revamp are not abstract. If Pakistan raised wheat yields to OECD levels, expanded domestic oilseed production to cover even one-fourth of current imports, and cut post-harvest losses of fruits and vegetables by half, the combined savings and earnings could exceed seven to eight billion dollars annually. More importantly, such reforms would stabilize domestic food prices, improve nutrition, and create export surpluses that enhance Pakistan’s global economic standing. But realizing this potential requires a state that is both capable and committed. Market signals alone cannot deliver surpluses, cold chains, or nutritional balance. A government that governs with integrity and intervenes directly where needed—in research, subsidies, infrastructure, and regulation—is the indispensable foundation of any lasting agricultural overhaul.

Demographic Pressure and Food Security

Pakistan today stands at a demographic crossroads. With a population of approximately 241 million in 2025, projected to rise to nearly 350 million by 2050 (UN Population Division, 2022), the country faces an urgent question: can it feed itself in the decades to come? A growing population is not inherently a burden. For a developing country, it is a source of labor, dynamism, and potential economic strength. Demographic expansion fuels industry, services, and agriculture alike. However, this population growth will only be a national asset if Pakistan has the capacity to provide affordable, sufficient, and nutritious food. If that duty is neglected, the same growth becomes a liability, driving poverty, malnutrition, and unrest.

Feeding such a population requires a serious reckoning with demand projections. By 2050, national wheat demand is expected to rise to 45–50 million tonnes, compared to current production levels of around 27–30 million tonnes (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2023). Wheat imports currently average 3–4 million tonnes per year, edible oil imports are around 3 million tonnes annually, and pulses are sourced overwhelmingly from abroad. These dependencies make Pakistan acutely vulnerable to global shocks. The Russia–Ukraine war demonstrated how quickly wheat prices can spike worldwide, leaving import-dependent nations struggling. In the event of a broader conflict or crisis that disrupted trade, the implications for Pakistan would be severe.

The recent experience of Gaza illustrates this hard truth: in times of crisis, nations cannot rely on the international community to prioritize their survival. When food supplies are disrupted by war or blockade, the world largely looks away, and populations are left to fend for themselves. Pakistan must absorb this lesson. No nation will step in to guarantee food for 241 million people, much less 350 million in the future. The responsibility rests squarely on the Pakistani state to ensure that its people do not go hungry.

This question becomes even sharper when considered in the context of national security. If Pakistan’s imports of wheat, oil, or pulses were suddenly cut off in a conflict scenario, the country would struggle to sustain its population on domestic production alone. Current wheat output already runs a deficit of 10 to 15 percent relative to demand. Oilseeds and pulses, which are imported in massive quantities, could not be replaced in the short term. While fruits, vegetables, and dairy are produced in surplus, these cannot substitute for staples in caloric or nutritional terms. The result would be rapid food inflation, rationing, and widespread hunger. In other words, Pakistan’s food dependency is not simply an economic weakness but a strategic vulnerability.

To meet the challenge, Pakistan must aim to become fundamentally self-sufficient in at least its core staples: wheat, pulses, and edible oils. Population growth ensures that national food demand will rise steadily in the coming decades. Whether this growth becomes a source of strength or weakness depends entirely on the choices made today. An agricultural system that generates consistent surpluses would stabilize prices, protect against global shocks, and ensure that the state fulfills its most basic duty: to feed its people. An agricultural system left unreformed, by contrast, would leave the nation perpetually exposed to external disruptions, with the risk that millions could face hunger during times of crisis.

Recommendations

Agriculture in Pakistan requires a fundamental restructuring if it is to meet the country’s long-term needs. With population growth accelerating and import dependence rising, the state must act as the primary guarantor of food security. Experience from countries such as China demonstrates that state-led coordination, investment in infrastructure, and scientific guidance are essential to building an agricultural system that is resilient and productive.

Water management should be the first priority. Per capita water availability has declined to approximately 900 cubic meters, a figure that places Pakistan well below the United Nations threshold for water scarcity. Since agriculture consumes more than ninety percent of freshwater resources, efficiency must be improved. A national program that expands drip and sprinkler irrigation could raise water use efficiency far above the current level of thirty to thirty five percent. Lining canals, repairing distribution networks, and establishing clear groundwater regulation are also necessary to prevent the depletion of aquifers and to ensure that the Indus Basin system serves national rather than narrow interests.

Mechanization and research are equally important. Pakistan has fewer than one tractor per 100 hectares, compared with more than four in India and ten in advanced economies. This gap directly reduces yields and raises costs. Establishing district-level centers where farmers can access equipment such as tractors, harvesters, and drones under state management would allow smallholders to benefit from mechanization without prohibitive costs. The Pakistan Agricultural Research Council should be revitalized as a central body for agricultural science, focusing on improved seed varieties, pest resistance, and climate adaptation. Agricultural research consistently produces high returns on investment, yet Pakistan’s commitment to this area remains limited.

Crop planning and diversification must also be addressed. At present, large tracts of land are devoted to wheat and sugarcane, while crops that Pakistan imports in large quantities, including pulses and oilseeds, are neglected. A state-led approach to crop allocation can ensure that land use is aligned with national food security objectives. Strategic reserves of wheat, pulses, and edible oils should be maintained and rotated under government management to reduce vulnerability to global price shocks. At the same time, high value exports such as mangoes, dates, and basmati rice should be supported with a coordinated branding strategy that positions them in international markets as premium products.

Infrastructure and value chains remain a weak link. Less than ten percent of perishable produce is transported with refrigeration, and losses from inadequate storage and transport reach thirty to forty percent. Developing state-managed cold storage networks, expanding rural road connectivity, and building food processing hubs would significantly reduce waste and increase rural incomes. In the dairy sector, Pakistan is the fourth largest producer of milk worldwide, yet less than ten percent of this production is processed into value-added products. Expanding processing capacity under public coordination would improve nutrition and enhance export potential.

Finally, governance must emphasize integrity. Food security cannot be subordinated to private interests or political lobbies. It must be guided by a national food security strategy that places the needs of the population first. The state must take responsibility for planning, investment, and distribution while holding itself accountable to outcomes measured in nutrition, productivity, and stability.

Conclusion

Pakistan’s agricultural sector faces a choice between continuing along its present trajectory of low productivity and import dependence or undertaking a comprehensive restructuring guided by the state. The risks of inaction are clear. With a population projected to reach 350 million by 2050, demand for wheat alone will exceed 45 million tonnes annually, far above current levels of production. Heavy dependence on imported pulses and edible oils already places billions of dollars of strain on the balance of payments each year. In times of global crisis or conflict, these vulnerabilities could translate into food shortages and widespread insecurity.

The reforms outlined above provide a pathway toward resilience. By investing in efficient water management, modernizing equipment and research, directing crop allocation, building infrastructure, and ensuring strong governance, Pakistan can move toward genuine food self-sufficiency. These measures would stabilize domestic prices, reduce import bills, and protect citizens from external shocks. They would also allow Pakistan to turn agricultural surpluses into export earnings through strategic branding of its best produce.

Food security must be understood as the foremost duty of the state. It underpins social stability, economic growth, and national security. If Pakistan commits to a coherent national food security strategy, it can transform agriculture into a foundation of strength rather than a source of vulnerability. The choice is between dependency and self-reliance, and the consequences of that choice will shape the future of the country for decades to come.